Few parents will ever hear that their child has a birth defect called craniosynostosis, but for those who do, the diagnosis can be devastating.

One in 2,000 infants is born with craniosynostosis, a disease in which two or more sections of the skull grow together prematurely. “Craino” relates to the head, “syn” is Greek for together and “ostosis” refers to bone growth.

A newborn’s skull is divided into six sections separated by fibrous gaps called sutures to allow room for the brain to grow. Usually these spaces fuse between the time the baby is about two years old and early adulthood, depending on the suture. When this happens too early, the brain continues to grow and causes the head to become misshapen.

In some cases craniosynostosis issyndromic, which means it is accompanied by other medical concerns such as problems with the heart and the urinary and genital organs. More commonly, children have no medical problems besides craniosynostosis.

Non-syndromic craniosynostosis usually is not inherited, but sometimes it can be passed along by the parents, said Rita Shiang, Ph.D., a geneticist and associate professor at the Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) School of Medicine, where she is researching the disease.

“Having two people with non-syndromic craniosynostosis in the same family is very rare. In those cases we definitely think it is inherited. A lot of time it involves a parent and child,” Shiang said.

Dr. Jeffrey Hanzel, a retired Richmond pediatrician, says he encountered only three cases of craniosynostosis in 45 years of practice. All were non-syndromic. He said it is critical to determine whether other conditions are involved, as is the case with syndromic craniosynostosis.

“It takes a good bit of judgment and knowledge to be sure,” he said. “The prognosis tends to be better with the non-syndromic form.”

Dr. Hanzel stressed the importance of a team approach to treating craniosynostosis, including the pediatrician, pediatric plastic surgeon, pediatric neurosurgeon and geneticist.

“We are trying to identify the genes that cause non-syndromic craniosynostosis, Shiang said. “For the syndromic form, most of the genes have been identified but non-syndromic is more complicated. There also may be some environmental factors such as intrauterine pressure during pregnancy.”

Genes provide the instruction manual for building and maintaining the body. Humans have about 20,500 genes, and half of each gene is inherited from each parent.

Genes are made of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), which forms a double helix with each half of the gene. If a gene mutates from its correct form, disease can result.

Shiang said her research is aimed at determining what can be done to prevent the disease as well as helping reassure parents that it was not their fault that the child was born with non-syndromic craniosynostosis.

“The questions that pediatricians get most often is ‘Did I do anything wrong?’ and ‘Why did this happen?’ Our research should help answer those questions,” Shiang said.

Dr. Jennifer Rhodes, a pediatric plastic surgeon, sees most cases of non-syndromic craniosynostosis at the VCU Medical Center. She asks parents if they would like to have their child enrolled in a study of the disease. If the parents agree, blood or saliva samples are taken to undergo genetic sequencing.

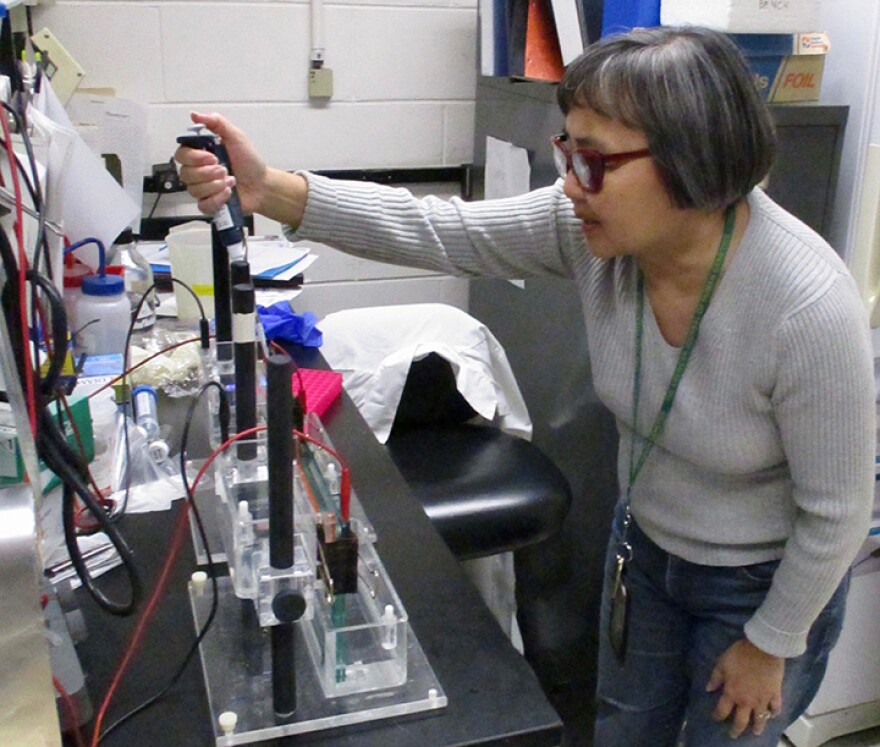

“We look for variances in the genes that might cause the disease,” Shiang said. Genes with suspect mutations are created inzebrafish, through gene editing, to see if the genes create the same disease in the fish.

Zebrafish commonly are used in genetic studies. “They are vertebrates and more cost- effective to study than mice,” she said. About 70 percent of a zebrafish genes are the same as humans.

Surgeons treat craniosynostosis by recreating the suture and correcting the shape of the head so the brain can grow normally. Most children have normal cognitive development and good cosmetic results. Early diagnosis and treatment are key, according to information from the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

Children’s Hospital at VCU offers a variety of approaches to treat craniosynostosis. Treatment is individualized for each patient and family, Dr. Rhodes said.

Shiang also has done genetic research on Treacher Collins syndrome, a disease that affects bone and tissue development of the face; Wolfram syndrome, which involves diabetes, loss of vision and hearing; as well as genetic research on schizophrenia and cancer.