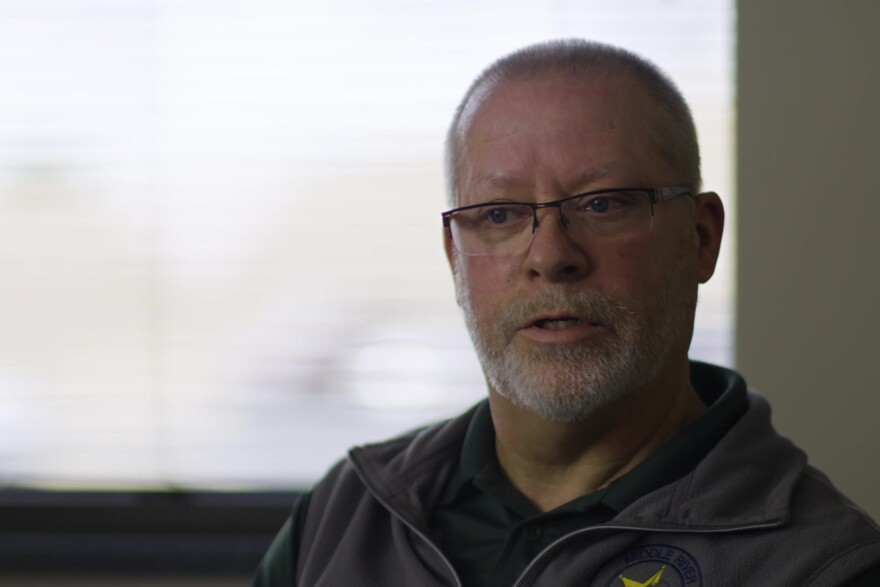

Jeff Newton retired from the U.S. Army in 1996 and went into the jail business. “I find it fascinating,” said Newton, former superintendent of Middle River Regional Jail in Verona. He has worked in prisons, too, but prefers working in a local jail because “it provides you an opportunity to engage individuals that have run afoul of the criminal justice system and provide them an opportunity to change.”

But Newton’s desire to rehabilitate prisoners — rather than simply warehouse them — is frustrated by chronic overcrowding at the facility. “The jail was built with a capacity to house 396 offenders,” he said. “Since 2015, we’ve been operating at about 200% to 220% of that capacity.”

In January 2021, the jail authority proposed a $39.5 million renovation and expansion of Middle River. The proposal became a lightning rod for the community, many of whom would rather address the causes of mass incarceration than invest public dollars in larger jails.

The pressures to expand Middle River Regional Jail reflect the overcrowding problems that many rural and urban jails face. The challenges run the gamut from inmate and staff safety to unhealthy conditions. Local jails also often become de facto holding areas for the mentally ill. But for many citizens, the issue boils down to the need to revamp a criminal justice system that puts too many people behind bars.

The data are astounding. Since 1970, the number of incarcerated adults in the U.S. has grown from 200,000 to over 2 million today. In that time, the U.S. population increased 61%, while the prison population grew 440%.

Since the ’80s, many more people are being incarcerated for drug offenses, said Gloria Rhodes, associate professor at Eastern Mennonite University’s Center for Justice & Peacebuilding. “More people of brown and black skin are there than white people,” she added. “Those are all structural problems that need to be addressed. And so, one of the ways of saying let’s address this is to say, ‘Stop. Let’s not build this building. Let’s look at what’s causing more people to come.’”

Jesse Crosson formed his views on incarceration from inside a prison cell. Raised with traditional values in a rural community near Charlottesville, he discovered cocaine at age 17, and it quickly consumed his life. “I went from a kid taking a year off from college who had made some dumb mistakes to just completely out of my mind,” he said. “I was arrested for a shooting and a robbery.”

Prison, however, was a lifesaver for Crosson: “I needed that immediate incapacitation. I needed to be stopped and sobered up.” Beyond that, he thrived on the love and encouragement he got from his support system on the outside. “That was what I needed to become a different person and the Department of Corrections didn't teach me that.”

So, if prisons are ill-equipped to rehabilitate prisoners and communities are being pressured to put fewer people behind bars, what’s the alternative?

One approach is restorative justice.

For example, Albemarle County and the City of Charlottesville have initiated a restorative justice diversion program as an alternative to prosecution. Programs like this focus on the harmful impact of a crime and define what can be done to repair that harm, while holding the offender accountable. Key to the process is a face-to-face meeting between the offender and victim, moderated by a trained facilitator.

For the technique to succeed, the parties have to let go of preconceived notions about prosecution. These discussions focus on healing, rather than punishment. They affirm that the survivor has been wronged and has suffered. Then the conversation turns to solutions: How can we make this better?

For others, the path to reducing jail populations starts with rendering justice more fairly. Activists like Hannah Wittmer are quick to point out that, relative to the general population, a disproportionate percentage of inmates at Middle River are Black.

Elaine Rose, pastor of Promiseland Christian Fellowship Church in Staunton, is particularly sensitive to the signs of systemic racism in the community. “All of my sons have been stopped by police here. I've been racially profiled here. There are days and times where I'm terrified if they'll make it home alive.”

Meanwhile, as of December 2022, the expansion proposal for Middle River has been put on hold. The jail’s average daily population has dropped to 547, nearly 30% fewer than when the expansion was proposed.

That’s a win for people like Crosson, who has become an activist and behavioral therapist since serving his sentence. Prisons have become entrenched in set ways of operating and people don’t want to admit they don’t work, he said.

In comparison, it’s a lot harder to work toward a more equitable criminal justice system, Crosson said. “The first and foremost change would be to focus on rehabilitation, rather than punishment. Until we provide access to those resources, we’ll never know who is capable of change and who isn’t.”

This article is based on the Justice episode from the new VPM docu-series “Life in the Heart Land.” The series gets to the heart of those creating unique solutions to rural America’s toughest challenges.

Jeff Newton was the current Superintendent of Middle River Regional Jail during the filming of this episode’s interview. Newton retired in June 2022.

Watch Thursdays at 8:30 p.m. on VPM PBS or anytime on the PBS App.

Visit vpm.org/heartland to learn more.