As an impressionable design student, Scott Tiernan was traveling in Scandinavia when he had an eye-opening discovery: a sheet of refabricated plastic that captured his imagination.

“I had never seen anything like it before — and it was just plastic,” he said. “So I did some research and realized ‘I can make this.’”

That experience ignited Tiernan’s passion for recycling. When he returned to Virginia, he launched POP Plastic, a small Staunton business that converts local post-consumer plastic into furniture and home goods. It’s his personal way to counter the wastefulness of a throwaway economy while giving back to his community.

“I’m trying to be part of the solution,” he said.

“Like many small towns, Staunton is stuck in the middle between metropolitan areas with easy access to recycling infrastructure and remote rural areas that lack it,” said Jeff Johnston, the city’s director of public works. And while he’s convinced Staunton’s citizens want to recycle, Johnston is hard-pressed to provide that service.

“I had a source for #1 and #2 plastic,” Johnston said. “No one in the area was taking #4 and #5 plastic, and that’s when I ran into Scott Tiernan.”

They talked about the city’s need to offload unwanted plastic and Tiernan’s need for the material to stoke his business. “If you can collect the plastic that I need, I think that I can help you out,” Tiernan offered.

Like in Staunton, recycling is a persistent problem in many rural communities, which often lack the staff to manage it, easy access to materials recovery facilities and the economies of scale that make big-city recycling programs less costly to operate and maintain.

Beyond that, the culture of recycling is very different in small towns and rural counties compared to cities. Staunton is a good example. A lot of the people who relocate to the area from Washington, D.C., and New York City have to learn new habits.

“Recycling doesn't work the same way,” said Morgan Shrewsbury, environmental programs manager at the Augusta Staunton Land Fill. “You don't have a dedicated recycling truck or single-stream. You are responsible for disposing of it yourself. There’s no one coming to pick it up at the curb.”

The problem grew more dire in 2017 when China announced Operation National Sword, a ban on importing waste materials — including plastics. “When China went away from that market, we had to respond as a country to be able to build up the infrastructure to take that material,” said Dylan de Thomas, vice president of external affairs at The Recycling Partnership in Washington.

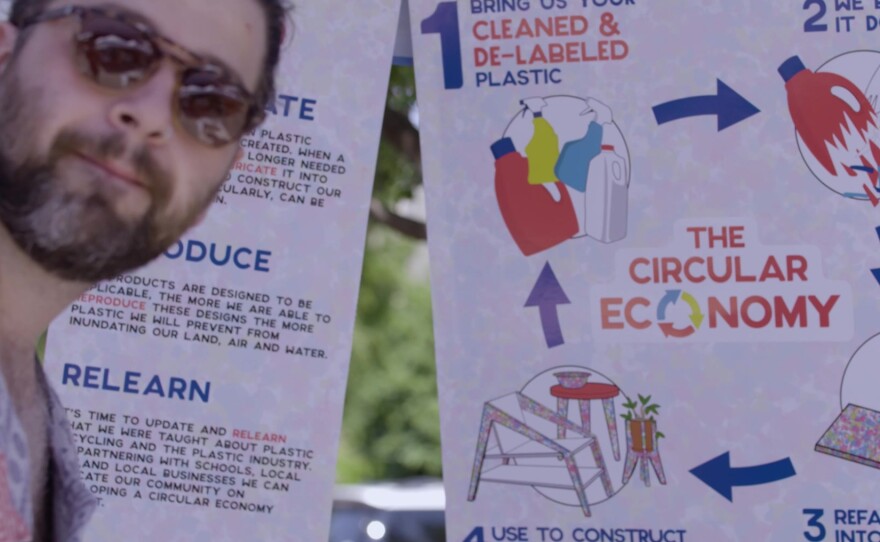

Communities are trying to shift from a linear economy, where people use something and then throw it out, to a circular economy where people reuse materials over and over, he explained.

One key barrier to achieving that circular economy is that more than 40 million Americans lack the same access to recycling service that they have to trash service, said Jessica Levine, diversity and inclusion manager at The Recycling Partnership. “Closing the equity gap to recycling in the U.S. — that’s not something that is a one-off,” she added. “That is something that takes time, and it’s going to take a collective effort.”

Even well-intentioned businesspeople like Tiernan have to clear many hurdles to be part of the solution. His original home-based operation was classified by the city as “industrial processing.” So he was forced to find a new location outside of a residential neighborhood where he could shred and melt plastic.

“I felt horrible, but at the same time I was obligated to throw the flag and say, ‘This is not a location that will work,’” said Johnston. Later, he added: “From a personal standpoint, I want Scott to succeed. From a professional standpoint, I need a place to take #4 and #5 plastics.”

On a practical level, as people continue to buy packaged goods, the trash they create needs somewhere to go. “You can go the easy route and you can put it in a hole in the ground,” said de Thomas. “Where are those holes in the ground? They’re often in rural communities.”

At the Augusta Staunton Land Fill, crews process about 500 tons of garbage a day, said Cole Seldomridge, acting Director of Solid Waste Management. It’s a sophisticated operation designed to protect the environment. The landfill has a liner system completely beneath it. There’s also a drainage system that collects the water flowing off the trash and diverts it to a treatment plant.

“Right now, it’s the best option we have,” said Seldomridge.

Meanwhile, Tiernan continues to pursue his dream of reusing materials rather than discarding them. For him, it’s about teaching his community how to leave the world a better place than they found it. “That’s what I want to give to our community,” he said. “That’s what I want to give to my children.”

This article is based on the Recycling episode from the new VPM docu-series “Life in the Heart Land.” The series gets to the heart of those creating unique solutions to rural America’s toughest challenges.

Watch Thursdays at 8:30 on VPM PBS or anytime on the PBS App.

Visit vpm.org/heartland to learn more.