More than 20 people are gathered at the foot of a large hill, near Gilpin Court, on the other side of the historically white Shockoe Hill Cemetery.

Emily Stock, Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation’s (DRPT) manager of rail planning, organized the group to talk about a high-speed rail project called “DC2RVA” that it wants to construct here.

“The DC2RVA project started in 2014,” says Stock to the group. “And we met many of you all through the process.”

Most of the academics, archaeologists, preservationists, museum directors, advocates and others in the group are here because for more than a year family historian Lenora McQueen has meticulously researched this place, emailing the group regular updates as she has helped uncover its hidden past.

In 2017, McQueen came to Charlottesville from her home in Texas to speak at a slavery symposium at the University of Virginia. While in Virginia, she took a trip to the Virginia Historical Society in Richmond, where she learned that her fourth great grandmother was buried in the city around 1857. But she did not recognize the graveyard, so she looked at a map, punched the location into her GPS and set out to find it.

“I didn’t recognize it as a cemetery when I got there, I found it rather confusing,” said McQueen. She recalls seeing a desolate hillside, with Interstate 64 running over it and an abandoned gas station at the top. She wondered if her GPS was broken.

“I drove down Fifth Street and across the bridge,” she says. “I turned around, I turned left and went down the hill into that gully and crossed the railroad tracks and turned around. And thought, I hope this is not it, you know, please don't be it, but that was it. That was exactly it.”

From 1816 to 1879 this was Richmond’s main African American graveyard, where, according to McQueen’s research, more than 20,000 people were buried, including at least five of her ancestors.

But burial records are thin, and gravestones have long since disappeared. In fact, over the last 150 years, the entire graveyard’s been destroyed. First, an 1883 article described workers using bones as infill while constructing North Fifth Street through the graveyard. Then, officials laid a rail line through it, a viaduct, another street, and in the 1950’s, workers hacked through it to build I-64.

Now, it’s where officials plan to build a high-speed rail project, and DRPT’s Emily Stock says they want to be respectful of the past.

“There have been mistakes made in the past and I would like to see a better balance and better preservation and memorialization of sites,” says Stock.

To try and strike that balance, the state hired cultural resource firm Dovetail, which keeps projects in line with the National Historic Preservation Act and the National Environmental Policy Act. Dovetail President Kerri Barile helped lead the large group of concerned professionals through the site, telling them that there could still be human remains buried in the area. She explains that DRPT and Dovetail have pledged several commitments.

“The first, is to take this very scant research that’s been collected and to do a full blown landscape analysis,” says Barile.

That process includes the challenging task of finding people whose ancestors were buried there, providing them with records to trace their histories -- which have largely been covered up -- and then working with the city to properly recognize that history. To date, McQueen is the only descendant who has publicly traced family members to this graveyard.

“Number two, is that archaeological testing will be done in any areas that will be disturbed,” Barile added. The final commitment, she says, is to have an archaeological monitor on site during the construction process to ensure no human bones are unwittingly disturbed.

But Dovetail will only be investigating the construction area itself, and not the surrounding graveyard, which is much larger and carries a greater likelihood of finding remains. Also, the site’s been repeatedly disturbed for so long that finding intact remains is unlikely, says Ryan Smith, a history professor at VCU.

“It's pretty clear that there's not much up there that's been entirely undisturbed,” says Smith. “But an argument that we've been trying to make is that the presence of undisturbed remains should not be the only criteria for the historical importance of this ground. And especially if they were disturbed, we want to avoid other levels of disturbance that these remains have surely suffered.”

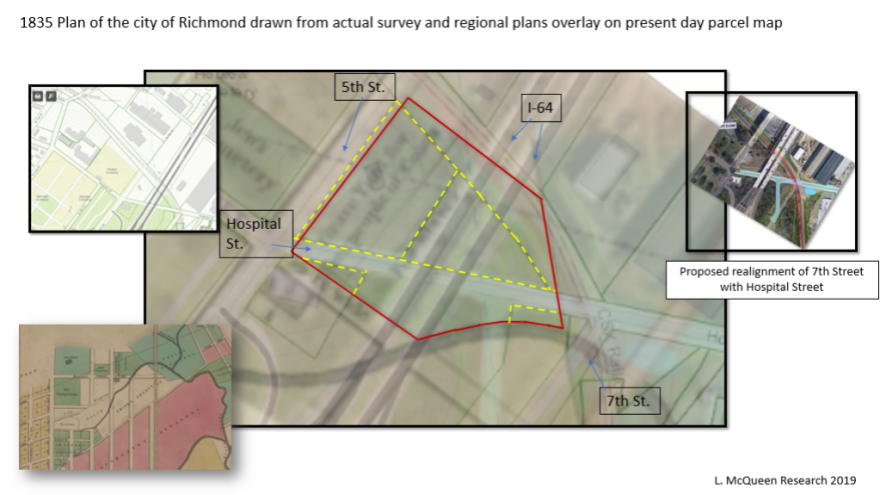

Reclaiming the sacredness of the space is key, says McQueen. She also says project officials are using a map showing the graveyard as smaller than it actually was, which may further limit the project’s study.

Many concerned parties see these, and other points of concern, and note that all of the project’s main decision makers are white.

“If it was their ancestors’ graves, I would think that their response would be a whole lot different,” says McQueen. “It’s really not acceptable. It’s really not acceptable.”

McQueen and other historians say ideally all roads and rails should be rerouted around the graveyard. Project officials say that’s unprecedented and haven’t considered the idea. At the very least, McQueen says she’d like to see the site reclaimed in another way, with a memorial, perhaps a scene of a burial ceremony like the one she imagines for her ancestors.