The Howard Baugh Chapter of the Tuskegee Airmen meets every month to honor the flag, their country and the first Black soldiers trained to fly in the United States. Retired Army Colonel Porcher Taylor is 94 and the oldest member.

"They were number one, number one," he said.

Bill McGee's grandchildren are the youngest in attendance. Sean and Kameron say they love to fly with their grandfather because "we get to see the sky and what the town looks like from above.”

McGee says he looks forward to the day they will fly him around. Meanwhile, he says the chapter is “reaching out and touching these young men for the future.”

Times were quite different for the original Tuskegee Airmen. Karen Sherry, the Museum Collections Curator at the Virginia Museum of History and Culture, says the men were, “willing to sacrifice for their country at a time when their country was not treating them as full equals.”

In 1941 the military was still segregated. But bowing to pressure from civil rights groups, the US Army formed the all-Black 99th Fighter Squadron and training field at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama.

Richard Baugh, son of the chapter's namesake, serves as the treasurer.

“There was a study conducted by the War Department in 1925 that basically said African Americans were a feckless race, didn’t have the intelligence to operate intricate, mechanical devices," said Baugh. "And they were also cowards and couldn’t organize themselves in a combat situation and would be too afraid.”

Howard Baugh was born in Petersburg in 1920 and graduated from Virginia State College in 1941. He enlisted in the US Army as an aviation cadet and was accepted into the newly-formed Tuskegee Airman. “They had to start to fight for the right to fight for their country,” said Richard Baugh.

Another son, Howard Baugh Jr., said there were many white people who did not want to see the Tuskegee Airmen succeed, but his father was determined to prove them wrong.

“We learned with whites and black, if we worked together, we could accomplish a whole lot of things,” he said.

Almost 1,000 pilots were trained at Tuskegee. They flew more than 15,000 sorties in Europe and North Africa during World War II and their performance earned them more than 150 Distinguished Flying Crosses. The Tuskegee Program also trained nearly 14,000 navigators, control tower operators and ground crews - all African Americans.

Rep. Donald McEachin, a Democratic Congressman who represents the 4th District, said the Airmen paved the way for integration in the military.

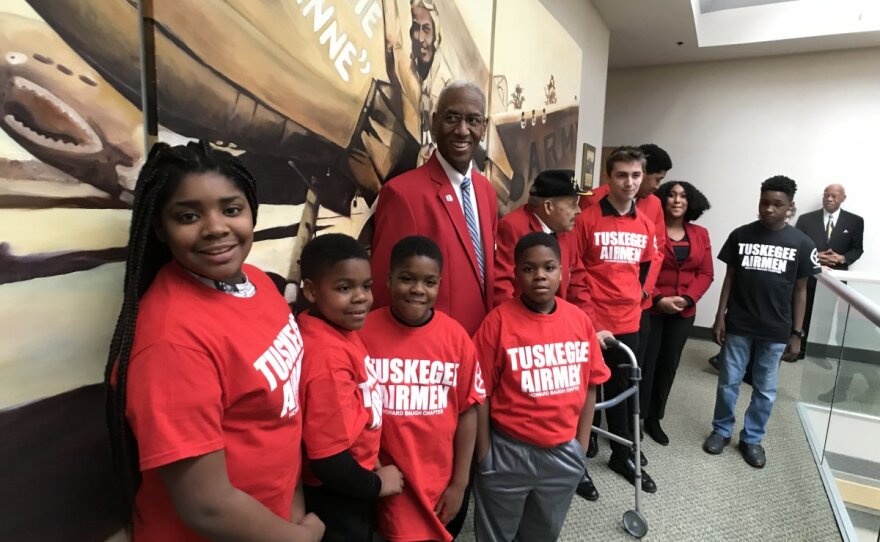

“Shortly after the war, Truman desegregated the armed services and it was in large part because of folks like the Tuskegee Airmen,” McEachin said. He was made an honorary member of the chapter at their January meeting, receiving one of the distinguishable red jackets that Airmen wear.

Retired Army Colonel Porcher Taylor was one of the founders of the Baugh chapter. Taylor attended Tuskegee Institute after the war and knew some of the pilots. In the early days, the chapter met behind his home.

“Right on the back porch of my house. We had some wonderful meetings there," Taylor told VPM. “I did my very best in the City of Petersburg, to make it known, that 'Hey, hey folks, we have a chapter here, of the famous Tuskegee Airmen.'”

They named the chapter after the late Baugh, a Petersburg native who rose to the rank of Lt. Colonel. After the war, he worked for Eastman Kodak in New York. But then he and his wife Constance returned to Petersburg where he spent his retirement sharing the stories of the Tuskegee Airmen.

It took them 15 years, but by 2018 the chapter raised $100,000 to install a full-sized statue to commemorate the Tuskegee Airman, modeled after Howard Baugh. It stands at the Black History Museum and Cultural Center in Richmond. Howard Baugh Jr. says the tribute sends a message: “What my Dad always said, climb your mountain and when you get to the top, help the next one in line."

To spread the word, the Howard Baugh Chapter organizes talks for school groups. They are buying a drone and beginning a program in March to teach young people how to fly and help them obtain a certified drone pilot’s license. In the future, they want to develop ground school and flight training opportunities and provide scholarships, as larger chapters do. Above all, they want the public to remember the legacy of the Tuskegee Airmen and what they had to overcome. Howard Baugh Jr. remembers being the only black student in the class and when his sixth grade teacher told him he couldn't become a pilot "because there were no colored pilots."

"And I told her that my dad was a pilot and she laughed and said, ‘Oh, you’re terribly mistaken, there are no colored pilots,” he said.

Howard Jr. went on to become one of United Airlines' first African-American pilots. Today, he tells the story and encourages a younger generation to keep the faith.

“I flew airplanes for 42 years. I stand on the wings of the Tuskegee Airmen,” said Howard Baugh Jr.

By keeping the memories alive, the chapter hopes to inspire the next generation to reach for the skies.

Both Richard and Howard Baugh will tell the story of the Tuskegee Airman at Henrico’s Libbie Mill Library Saturday at a free event from 4 to 5 pm. And on Feb. 25th, the Virginia War Memorial will feature them on their first live, interactive broadcast to schools across the country from the new C. Kenneth Wright Pavilion, named after the local businessman, philanthropist and World War II veteran.