The country’s political divide has been on clear display at school board meetings across the country all summer and this fall. That’s true too in Virginia, where education has taken central stage in the gubernatorial race.

Republican gubernatorial candidate Glenn Youngkin has latched onto the heated debates, falsely stating that CRT has moved into all Virginia schools and jumping on one of his opponents, Democrat Terry McAuliffe, for saying parents shouldn’t “be telling schools what they should teach.”

The dialogue about what say — if any — parents should have when it comes to what their kids are learning in schools has been at the center of much of the debate. One Youngkin campaign video features a Loudoun County parent who was upset over a book her high school senior was reading in an advanced placement literature class, Toni Morrison’s “Beloved.”

Loudoun County also made national headlines as a bitter fight unfolded over racism in the school district. In Central Virginia, similar fights are playing out in Hanover County.

CRT

On Nov. 9, the Hanover County School Board is slated to vote on updates to its policy on “teaching about sensitive or controversial topics.” The draft policy adds language explaining what controversial means.

“An issue is controversial when there are substantial differences of opinion about it on the local, national and international level and when those differences of opinion are accompanied by intense feelings and strong emotions” the policy states.

It also states that whenever there is doubt about if a topic is controversial, “teachers, students or student groups should consult with the principal to determine the degree of sensitivity of the school community regarding the issue.”

Pat Hunter-Jordan, president of the Hanover County NAACP chapter, worries policies like that could worsen an ongoing, national teacher shortage. She recalled a recent conversation with her 94-year-old mother, who was a teacher, during an October school board meeting.

“As we talked about the job of teaching, she said ‘I would not go back into the schools today. Because parents are trying to tell teachers what to teach,’” Hunter-Jordan said. “She said ‘we went to school to get degrees to share knowledge with children. And parents don't have that knowledge.’ She stated that they have opinions, which is not knowledge.”

“Controversial issues” have taken a place in national discourse as Republicans continue to rail against the teaching of Critical Race Theory, even as school districts reiterate that the nearly 50-year-old academic framework, which examines how social constructs of race lay the foundation of racism, is not being taught in K-12 schools.

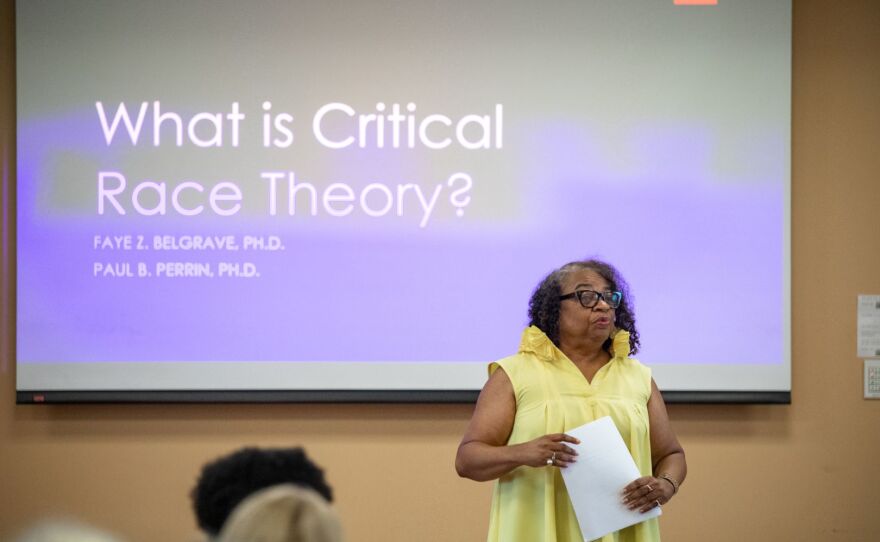

Conversations at Hanover school board meetings have been so heated that the county’s NAACP chapter decided to hold an informational session this summer so community members could learn more about what critical race theory actually is - and isn’t.

“We kept hearing, ‘don't teach this to our children’ and we don't teach it,” Jordan said. “We wanted people to understand what it really is and the fact that this is not something that is taught in school systems. We wanted to clarify that, and I wanted to do it without it being partisan.”

Two experts on the topic from Virginia Commonwealth University — psychology professors Faye Belgrave and Paul Perrin — explained what CRT is, and what it isn’t.

“Critical race theory really wants us to understand the significance of race and how race has impacted the experiences and the outcomes of people of color in this country,” Belgrave said. “It does not sugarcoat enslavement. Let's get the historical facts.”

Belgrave said there’s a common misconception that because CRT endorses equity, it is against equality.

“Critical Race Theory does not reject the principles of the civil rights movement of equality,” Belgrave said. “It endorses equity, which goes beyond equality. It acknowledges historical oppression and advocates for equity.”

Also, Belgrave said, the goal is not to make white people feel guilty or to blame for racial inequity.

“We want to encourage everyone, no matter what your race or ethnicity is, to acknowledge the significance of race and life experiences and outcomes for racial ethnic minorities,” Belgrave said. “Because we don't all start at the same place. A history of enslavement for Black people in this country has resulted in inequities that we're still catching up on, quite frankly.”

Equity in Hanover’s schools

The district’s first ever equity report was presented to the Hanover school board in May. The report showed that Black students are overrepresented in school discipline and underrepresented in advanced courses.

Those findings were upsetting for Melanie Bowers, a member of the equity community advisory board for Hanover County Public Schools. While the report was a good start, she said the data doesn’t paint a full picture of what’s going on.

She and others on the advisory board have been calling for the district to hire a third party to complete an equity audit, diving deeper into the data and analyzing a range of issues including school discipline. It’s the top priority the board identified in a list of recommendations submitted to the school board.

“It [the equity report] doesn’t drill down enough,” Bowers said. “What are they being disciplined for? You know, what are things that trigger a disciplinary action? What was the specific action that caused a suspension?”

Priority No. 2: hire a director of diversity, equity and inclusion at the district level to focus on diversity and equity in hiring among other things. Bowers says just knowing the percentage of white employees compared to Black employees isn’t enough.

“What positions are they in? Are they the custodial team? Are they the transportation? Are they the science teachers? Are they teaching math? Are they teaching government? Are they in assistant principal roles? Where are children seeing their representation? Because that matters, wherever we go, our children follow,” Bowers said. “If you look at Venus and Serena Williams, a lot more Black children started doing tennis, a lot more Black children are doing gymnastics now because of Simone Biles. When we see ourselves in situations, naturally children want to go there. And not that there's anything wrong with transportation specialists or custodial specialists. But it opens our eyes and gives us the ability to see ourselves as not having a ceiling or a cap.”

These are issues that are personal for Bowers and her family. She says her kids have experienced some microaggressions at school in the district. She says her daughter and sons have been called racial slurs. Bowers says she and her husband have also had to supplement certain course material to ensure their kids don’t just understand history as it's often been told: from the white perspective.

“What we do has been intentionally teaching our children like, okay, yes. They had the Declaration of Independence; the Declaration of Independence wasn't necessarily for us,” Bowers said.

“When the conversation goes to, you know, well our children are too young to learn about racism, our argument has been: our children experience it from the moment they leave our homes. I think at some point, we all have to come to the reality that this exists. We can't keep sweeping it under the rug. And we need to figure out how to better do this for the benefit of the kids.”

According to Ola Hawkins, chair of the Hanover County School Board, the board won’t vote directly on the committee’s recommendations, which she says is standard practice. Instead, they will be considered as the district crafts new policies and budgets.

The inequities in Hanover’s schools are reflected in the economics of the county. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the median household income for white Hanover residents is 33% higher than that of Black residents.

The disparity is even worse nationally, with the median white household earning nearly 60% more. Perrin says that backs another key point of CRT: that systemic and structural racism is embedded in institutions, perpetuating inequalities like the racial income gap.

“The average white family in the United States has about $110,000 of wealth, on average...the average Black family [has] just under $5,000,” Perrin said. “So what I would ask to folks who say, ‘race doesn't matter in the United States, there's no such thing as [systemic] racism,’ I would encourage you to think about the system that perpetuates that, that creates that. Where does that come from if there's not some system, some social force, that's creating inequity?”

Correction: We have corrected two errors in this piece and apologize for them. The story previously misspelled Melanie Bowers' name and misstated in a caption that the NAACP meeting was in August.