This article authored by Ryan Murphy was originally published by WHRO.

Virginia’s Latino residents have been more likely to catch Covid-19 over the last two years. A state report admits a lack of Spanish-speaking contact tracers and insufficient outreach in Spanish-speaking communities are partly to blame.

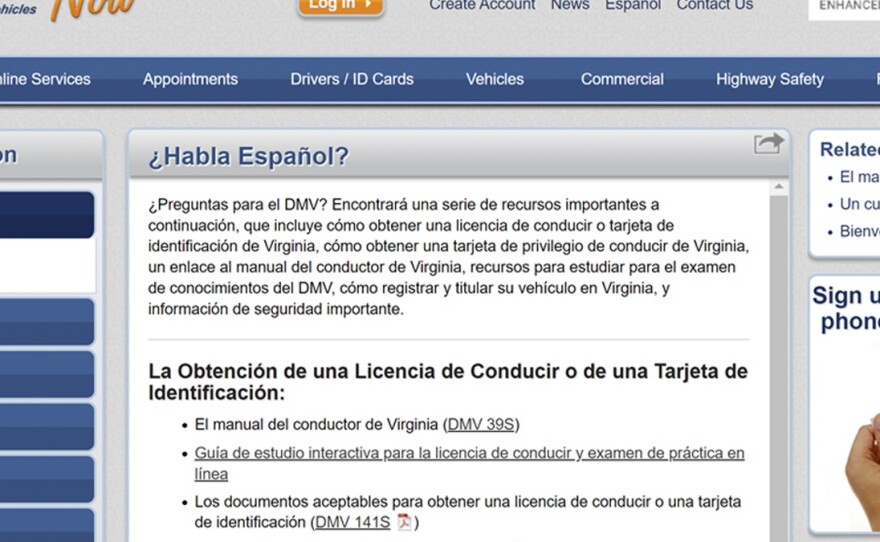

Accessing government services can be confusing enough, awash in a sea of acronyms and bureaucracies. Adding a language barrier on top of that can make navigating something like the Virginia Unemployment Commission or Department of Motor Vehicles nigh impossible.

"Despite efforts to improve language access suport and services for people with (limited English proficiency) and people with disabilities, accessibility to Virginia state government services is still a significant barrier," said the state report published last year.

Nearly half a million Virginians have limited English language proficiency.

Julian Baena is the treasurer of the Hispanic Chamber of Commerce of Coastal Virginia. He said many people in his community don’t speak English as their first language. That becomes a problem when they try to deal with the government, at every level. So Baena brought this issue up to someone he figured could do something to help: Gov. Glenn Youngkin.

“What we saw during COVID in this nation was… information is getting out there, we did a good job getting people's information. But it's all in English,” Baena told Youngkin during a town hall in Virginia Beach in February. “Something as simple as if I go to the Virginia.Gov website today, there is no [way] for me, for me to be able to read it in Spanish as a Spanish-speaking native.”

Youngkin said he wanted to talk with Baena more, but didn’t address the issue itself at the town hall. Baena told WHRO this week he still hasn’t heard from the governor. Youngkin’s office told WHRO several agencies are working on improving access, but didn’t give specifics.

This isn’t a new problem. A state report from 2004 pointed out language barriers across Virginia’s government in violation of federal requirements and recommended several fixes. Another report published last year found no evidence that anything from that 2004 report had been implemented. Seventeen years later, state services remain inaccessible to a growing number of Virginians.

The new report pointed out examples like the state’s redistricting process, which publishes information exclusively in English, and the DMV, where poor or non-existent translations made getting a driver’s license considerably more difficult for non-English speakers.

And it’s not just a lack of Spanish.

Starting in 2020, Korean-American groups in Northern Virginia criticized the state over the fact that the Virginia Unemployment Commission o ffers only English and Spanish translations. Korean is the third most spoken language in Virginia behind English and Spanish, with north of 30,000 speakers.