The next volley in the fight over prison housing practices in Virginia is set for Friday. The American Civil Liberties Union of Virginia will ask a federal judge in Big Stone Gap to certify the expansion of a lawsuit against the Virginia Department of Corrections and its administrators over segregated housing.

Currently, 12 plaintiffs who spent extended periods of time incarcerated in what the ACLU calls "solitary confinement" are seeking damages for alleged violations of their constitutional and statutory rights. The suit alleges that prison officials have knowingly and without good reason subjected incarcerated individuals to cruel and unusual punishment by keeping them in prolonged solitary confinement.

At Friday’s hearing, the plaintiffs will ask that the case be certified as a class-action lawsuit. If the court rules in their favor, the number of individuals who could be entitled to relief would expand to include anyone incarcerated under certain conditions at two supermax prisons in Wise County since 2011.

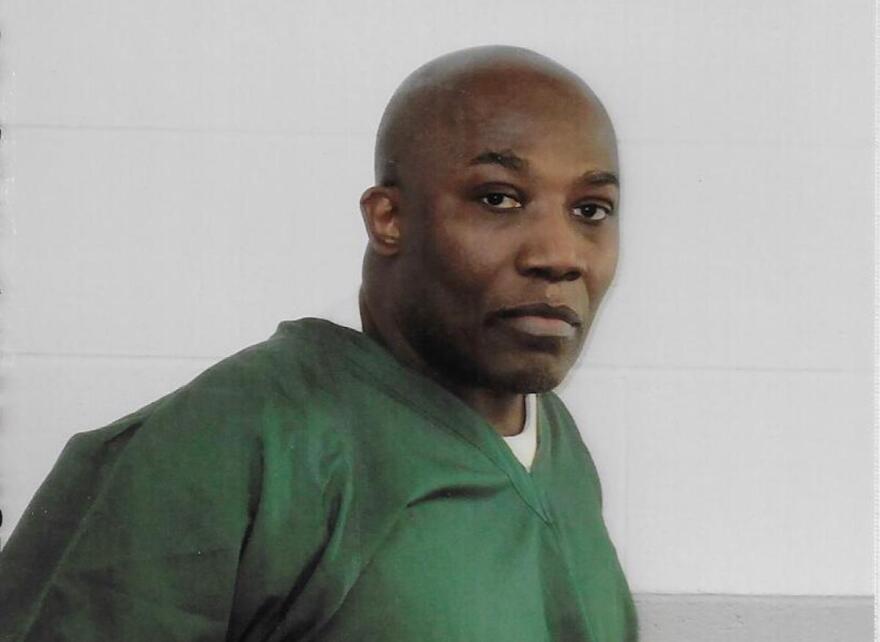

It was May 2019 when the ACLU initially filed the lawsuit on the behalf of William Thorpe and several others who experienced long-term segregated housing at Wallens Ridge or Red Onion state prisons, supermax facilities that house people convicted of violent felonies. Thorpe was incarcerated at both of these facilities.

According to the ACLU and court documents, Thorpe spent more than 20 years isolated in cells that were about the size of a parking space. He was allowed outside for only a few hours each day.

The ACLU, the Virginia Coalition Against Solitary Confinement and human rights activists worldwide refer to this practice as solitary confinement, and there is widespread agreement among health and human-rights professionals that the practice is inhumane. Medical professionals concur that deprivation of human contact can deteriorate an individual’s mental and physical well-being within just a few days. Symptoms might include headaches, hallucinations, loss of appetite and self-harm.

Virginia prison officials have argued that the practice doesn’t qualify as solitary confinement. VDOC guidelines assert that solitary is 22 or more hours of isolation in a cell without meaningful interaction with others.

VDOC said those removed from the general population because of behavior issues are in isolation for the safety of prison staff and other people who are incarcerated, and that they are kept in individual cells for no more than 20 hours each day. The department said the isolation is part of its restorative housing program (formerly called restrictive housing), which grants incarcerated people access to therapeutic programming and allows them to earn their way back into the general population.

A key component of the department’s restorative approach is the Step-Down program, which gives people who are incarcerated the opportunity for journaling exercises and group discussion with trained experts.

“We have interactive program aides. We have treatment officers. We have counselors. We have mental health practitioners that all facilitate that program,” said Lois Fegan, chief of restorative and diversionary housing for VDOC, in a 2021 interview with VPM News. “The inmates have the opportunity to do it together with other people in the restorative housing program. They also have the opportunity to kind of reflect and journal privately in their bed by themselves, and then they can come back to the group and they can process their thoughts.”

Demario Tyler — who is not a part of the lawsuit, but if it becomes a class action could be included — spent time in segregation at Wallens Ridge.

He said at the supermax facilities, “they go by their own rules” and that while the Step-Down program might be well-intentioned and could be helpful for those housed in lower security prisons, “They act like they’re following that, but they really don’t.”

Tyler described himself as a man with mental-health challenges. He lost his mother at a young age and grew up in foster homes. He was convicted of breaking into two restaurants in 2016 after being caught on camera looking for food and money.

Tyler said he was written up for nonviolent offenses at lower-level prisons and was moved several times before completing his sentence at Wallens Ridge in 2020. He claimed that while there, he was placed in segregation as punishment for having a mental-health crisis and asking to see a counselor.

He described “sitting in the hole for months at a time.” Tyler said being incarcerated — especially in isolation and most certainly for people who already have mental health issues — amplifies problems with impulse control.

“They just changed the name. It’s still solitary confinement. The only difference between solitary confinement then and now is that now they give us booklets to fill out,” Tyler said. “[B]ut we still sit in the hole for three or four months at a time, longer than that for some people.”

VDOC has held up its restorative housing program as an example of its mission to serve incarcerated people and broader society. Fegan said the program “represents a vision of offering opportunities for inmates that are in crisis, have some behavioral issues that need to be addressed, and in hopes of fostering a long-term public safety vision and reentry establishment goals for all the inmates in our care.”

Fegan cited numerous awards for the department’s overall excellence, as well as innovations in preparing people who are incarcerated for reentry into society and consistently low recidivism rates in Virginia, compared with other states.

The ACLU is alleging that people are placed in segregated housing for trivial or arbitrary reasons and then kept there for unreasonable lengths of time. The suit also claims that Step-Down is not administered in a way that gives prisoners any actual power to earn their way out. Additionally, the ACLU said the distinction between what VDOC calls restorative housing and what is considered solitary confinement is moot, if the people who are incarcerated have no meaningful interaction with others when they are out of their cells, whether that is two hours, four hours or slightly more per day.

“It turns more on the deprivation of normal, direct and meaningful social contact and access to positive environmental stimulation than it does the precise hours in a cell,” said Virginia ACLU lawyer Vishal Agraharkar. “For example, if you are taken out of [a] cell for a couple of hours every day and placed in a larger outdoor cage where you have no social contact with others, that’s still solitary by any reasonable definition.”

In previous reporting, VPM News spoke with family members of people who are included in the current lawsuit, as well as others who have experience with long-term isolation at Wallens Ridge or Red Onion.

Thorpe, who spent more than 20 years in isolation, was transferred to Texas soon after the ACLU filed its lawsuit in 2019. Denise Thorpe, his wife, said “he is still exiled to the Texas Department of Criminal Justice and still remains in solitary confinement. He has been in solitary confinement since 1996.”

Nicholas Reyes spent more than 12 years in segregated housing before the ACLU settled a lawsuit against VDOC on his behalf in 2021. Reyes is Salvadoran, and the ACLU said that his language and literacy skills prevented him from completing the Step-Down requirements for release from isolation. The state paid more than $100,000 to Reyes in the settlement and transferred him from Red Onion to the general population at Wallens Ridge.

In 2021, Fegan told VPM News that the department provides Step-Down materials in multiple languages, as well as translators for those who need them. She declined to say how long the language supports had been in place and would not comment on specific people or lawsuits.

In January, the ACLU and VDOC reached a settlement in Randy Burke’s case. Burke is a practicing Rastafarian who was segregated from the general population for more than 5 years. The ACLU said he was being punished for not cutting his hair, which would have been a violation of his religious beliefs. Burke was transferred back to his native U.S. Virgin Islands earlier this year.

Kimberly Jenkins-Snodgrass — the mother of Kevin Snodgrass Jr., who was incarcerated at Red Onion and is one of the plaintiffs in the ACLU’s lawsuit over the Step-Down program — said her son remained in isolation for more than 4 years. She said that her son was released from segregation in 2017, but claimed he was returned to solitary in 2018 in retaliation for her advocating to end the practice. Kevin Snodgrass is one of the named plaintiffs in the ACLU’s lawsuit against VDOC over Step Down.

One of the most widely publicized cases around segregated housing involves Tyquine Lee. Takeisha Brown, his mother and guardian, said that her son was diagnosed with a mental impairment when he was 8 years old. When Lee was 26 years old, he was placed in segregated housing at Red Onion and remained there for 600 days. Upon his release, Brown said her son was unable to communicate except in growls and barks and had lost 30 pounds. In 2021, Lee’s complaint against VDOC ended with a payment of $150,000 and a transfer to a prison outside of Virginia.

The Commonwealth of Virginia filed a motion to dismiss the ACLU’s current lawsuit, based on protection of individual employees under qualified immunity, but Judge James Jones denied that motion in Western District Federal Court in Big Stone Gap in 2021. The Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals in Richmond upheld that ruling in June.

On Friday, the ACLU will again be before Jones, asking him to certify the putative class-action lawsuit. A certification ruling is expected sometime this fall with evidentiary discovery to follow in January 2023. A trial could be scheduled by March 2024.