At the end of 2020, Richmond City Council approved its master plan for the city’s development, called “Richmond 300.” While the plan has earned a prestigious planning award and been credited for its community engagement process, councilmembers and the public still had reservations.

On Monday, City Council asked the Planning Commission to consider a long list of suggested changes in 2025. These proposals include planning for faster growth in the city, preserving the historic legacy of Jackson Ward, adjusting height regulations for buildings and measures to mitigate climate change.

The suggestions are largely symbolic, though. Richmond 300 itself is nonbinding, and these suggestions are being put forth for consideration only. The resolution passed Monday night originally sought to amend the master plan.

But this continued work on the Richmond 300 plan — alongside a rewrite of the city’s zoning ordinance, and an initial exploration of changing the city’s charter — points to institutional and legal changes for a city that has undergone a transformation in the past few decades.

In a July 2021 memo addressing proposed amendments, Maritza Pechin, of the Department of Planning and Development Review, classified 20 of the proposals as “fundamental” changes to the plan that would require extensive public engagement. All 20 of these “fundamental” adjustments were included in Monday’s amendments.

Damian Pitt, an urban planning professor at Virginia Commonwealth University, said the proposed amendments were contradictory.

“There's a lot of stuff scattered throughout here that basically would reduce the allowed building height or allowed density for certain neighborhoods, and which, again, is incongruous with the concept that we're going to be anticipating an even more aggressive growth rate than what's currently envisioned in the plan,” Pitt said.

The suggestions called for projecting aggressive growth that would require about 50,000 new housing units while also changing suggested land use in ways that discourage density.

Andreas Addison, who represents the West End 1st District on City Council, said some of Monday’s proposals came from conversations with neighborhood groups.

“We took those to heart, put those to the process of legislation,” he said. “On some of them, we've made some progress.”

Addison said some of the changes will be worked out through a rewrite of the city’s zoning ordinance.

“Rather than trying to pre-judge the decision before we do the action, those are going to be part of the exact public process of the next steps,” he said.

Councilor Ellen Robertson, of the 6th District around downtown, had reservations about the master plan when it was first passed.

“I felt that we needed to be sure without a questionable doubt that we included all of the neighborhoods that are managed by Richmond Redevelopment and Housing Authority,” she said. “Inclusion, affordable housing, all of that language is in there. The planners felt very confident that they had taken that into consideration. I disagreed.”

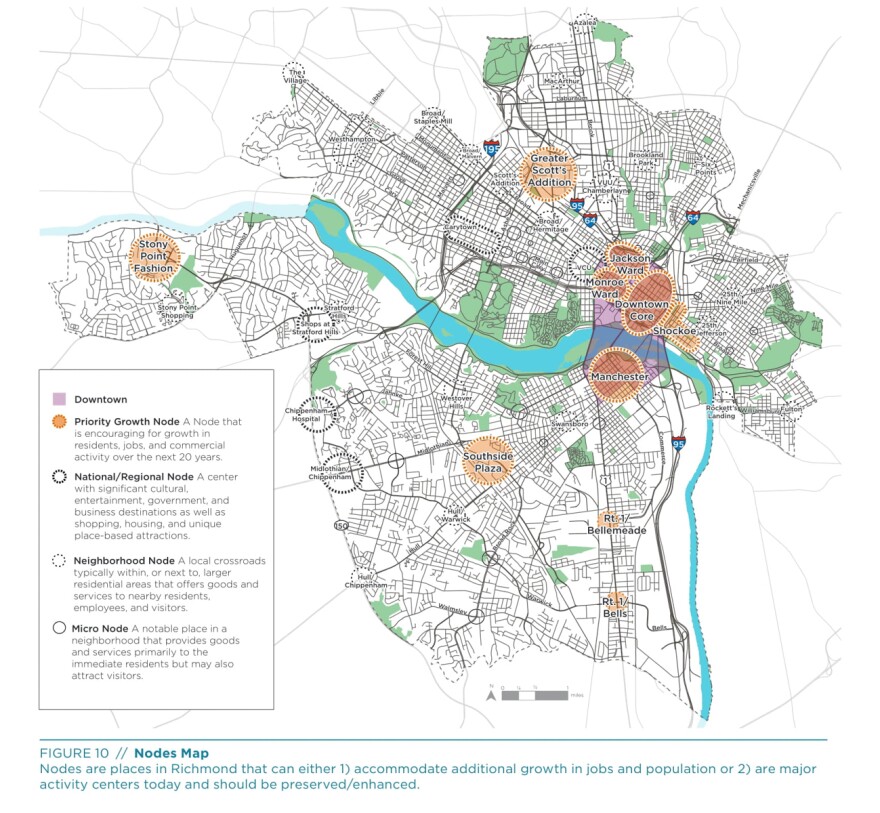

Robertson wanted public housing communities to be designated as nodes, which get special attention in the master plan. Planners identified 10 “priority growth nodes” where they want to especially encourage growth and development.

Robertson said the work to actually amend Richmond 300 to include RRHA properties as growth nodes is underway.

Affordable housing is also one of the concerns the Partnership for Smarter Growth brought up in Monday’s meeting. Stephen Wade, vice president of PSG’s board, saw good and bad in the master plan.

“While there's so much about this Richmond 300 plan that we think is fantastic, from increasing density — and in the right places — to making the city more socially and environmentally equitable, we are deeply concerned about the lack of clear affordable housing goals and expectations within new development,” Wade said in a Tuesday interview.

The ordinance passed Monday calls for the city planning commission to look at these amendments and suggestions in 2025. Pitt said doing that, rather than amending Richmond 300 outright, was an appropriate measure since it provides time to evaluate assumptions behind the amendments. But he still raised issues around the process.

“That's a fine resolution to what’s been a pretty frustrating, and I think poor governance process, to have these amendments lingering for two years,” he said. “Hopefully, we're not going to be, two years from now, just adopting this document as is with all of its inherent internal conflicts. But I don't think that that's the intent.”