Gordon Parks was among the first Black directors to make a studio film in Hollywood, back in 1969. But he’d amassed acclaim as a photographer before that.

"People knew who Gordon Parks was because of his work at Life Magazine,” said John Edwin Mason, history professor at the University of Virginia and co-director of the Holsinger Studio Portrait Project. “He was famous, but he was not a celebrity. His movies made him a celebrity. Life Magazine and his books had made him quite affluent. His movies made him rich. And so, it’s moving from fame to celebrity, and from affluence to great wealth.”

Parks likely is best known for directing the 1971 action film “Shaft,” a movie that showcased the era’s first Black action hero on screen. Several years later, he directed “Leadbelly,” a fictionalized account of the life of blues and folk singer Huddie Ledbetter.

As a part of its Black History Month programming, the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts is showing “Leadbelly” at 6:30 p.m. Friday. It serves as a companion to VMFA’s current exhibit, “Storied Strings: The Guitar in American Art.”

Mason took some time recently to discuss the writer, director and photographer’s career, and what it meant in American culture.

The following has been edited for length and clarity.

Dave Cantor: How did you first encounter Parks’ work?

Mason: I first encountered Parks through "Shaft,” his — as they say — “blaxploitation” movie.

I was still in high school, and we loved it. It was a lot of fun, right? In this period, it was still new to see Black heroes on screen, and it was still new to see black men beating up on white detectives and white crooks. It was an exhilarating movie. And I'm not going to say that it's a great movie, but it's a very good action thriller. And, of course, it has music by Isaac Hayes — that immortal soundtrack.

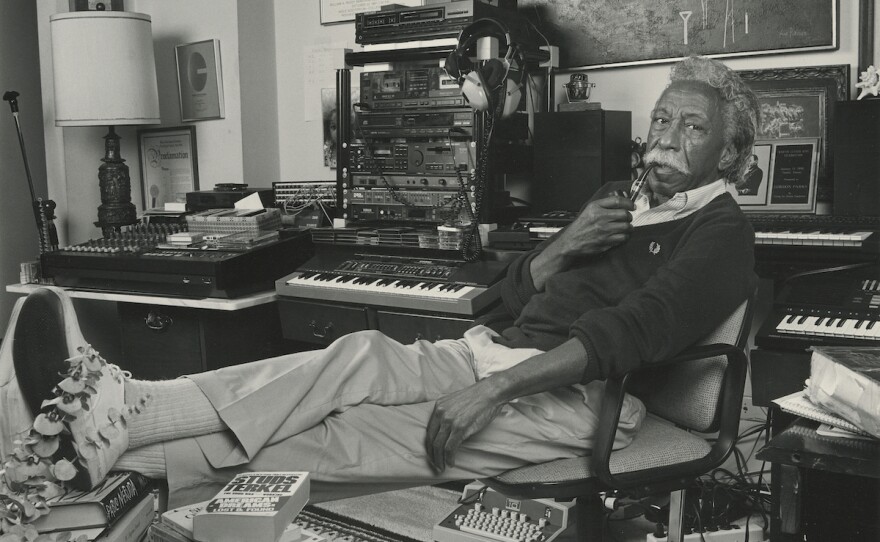

Let me think, no. You know what, I had already seen a documentary that CBS News did about Gordon Parks in 1968. And it was called “The Weapons of Gordon Parks.” That's a play on the title of his first memoir, “A Choice of Weapons.” It was a half-hour long. I've seen it since, and I know that it focuses on Parks as a photographer, but equally on Parks as a writer. And it showed him as a man of great cultivation. Somebody who is awakened every morning by classical music playing on the stereo and a man who lives in a high-rise near the United Nations on the East Side of New York. A man who smokes a pipe. A man who plays beautifully on a gorgeous concert grand piano in his apartment. A man who is often hunched over the typewriter, working on poetry or on one of his novels. And also, a man whose photography made a difference in the world.

Although in that CBS News documentary, his photography is downplayed a bit — surprisingly so because his photography more than his writing or his music is what made him famous. But, you know, I saw that and related to it a bit, because he was a man who was Black and who liked classical music. And I hadn't run into many Black people who liked classical music besides me, so it was nice to be reaffirmed.

But it was "Shaft” that really got me excited. You know, for the next couple of decades, the ’70s and ’80s, Parks was a celebrity. But I think he fell off my radar screen — like he fell off the radar screen of many people in the ’90s. And it was working intensively on Russell Lords’ exhibition about juvenile delinquents in Harlem, that's what got me focusing on Parks and really coming to terms with what he achieved as a photographer and as a writer.

You teach history, you're a photographer and you help run the Holsinger Studio Portrait Project. So, how does Parks' work slot into your own academic pursuits?

When I started working on bringing [the Lords] exhibition to Charlottesville, I was already writing about photography. I was writing about photography in South Africa. And I'd even written an article about a Life Magazine photographer, Margaret Bourke-White, who did a spectacular series of photo essays about South Africa.

So, I was familiar with Life Magazine and familiar with writing about photography. But one of the things I learned when I was working on the Gordon Parks exhibition here at UVA is that there was not a good analytical study of his work for Life Magazine. And the more that I looked at a whole series of photo essays that he did on the subjects of race and poverty, I came to see that he was one of the most influential spokespersons for Black America to a white audience in the 1940s, ’50s and ’60s. He played a role that I think was comparable to James Baldwin. You know, Baldwin was the great explainer to white people about Black America, or one of them.

[Parks] had the platform of Life Magazine, which reached tens of millions of white Americans every week — every single week. Parks was not as eloquent a writer as James Baldwin, but his photographs spoke just as eloquently as anything that Baldwin ever wrote. And just as powerfully and just as emotionally. And Parks also often supplied text for his photo essays. Once again, he was not a lyrical writer, but there's a rough and ready [quality] to his prose that's very, very effective.

I think he's been overlooked in terms of his impact on American society in those years.

Do you know how he moved from working at Life to getting into movies?

His very first movie, “The Learning Tree,” was based on his first novel, which was a novelization of his childhood. So, Parks always thought of Life as a springboard, a springboard to something else, and he wasn't always sure what that something else would be. ...

His interest in moviemaking goes way back to before he became a professional photographer. In his memoirs, he talks about watching a documentary movie in Chicago just before World War II. And it's a very exciting documentary about an attack on an American gunboat in China. It was photographed at the scene by somebody who was there, who endured the attack. And it really gripped Parks, the power of moviemaking to tell a story and to grab you emotionally and to draw you in. So, that was very much on his mind.

When he worked on photo essays, he sometimes took a movie camera along with him. So, he did a big story on an impoverished family in Brazil. They lived in a favela above Rio de Janeiro. And it's a story that became very famous about a young boy named Flávio and his family. Parks not only photographed it and not only wrote some of the texts that got published [alongside the photos], but he took his camera and made a movie about this family. Now, the movie, as far as I know, didn't get distributed. But it was Parks trying out a sort of first attempt at making a documentary film.

He worked on another photo essay, about 10 years later — 1967, 1968 — on a deeply impoverished family in Harlem. He also made a film about them, and this one did get distributed. It was shown on educational television in New York City in 1968 and won a local Emmy Award. So, this is before he goes to Hollywood — he's already working in film. And I think that he definitely saw film as a way where he could be more in control of the end product. He could reach even more people than he could reach at Life Magazine and tell these expansive stories that a magazine simply doesn't have the capacity to do.

It seems like these are all different audiences, maybe.

The thing about "The Learning Tree,” his first movie … . And I do have to stop and say that he became, when he made that movie, the first African American to make a Hollywood studio movie. There had been Black filmmakers before, but they had never worked for a Hollywood studio. He was the very first, so he opened that door to generations of Black movie directors. But “The Learning Tree” made money and it made money not just off of African American audiences but a wide audience.

So, one of the things that it demonstrated to Hollywood was that white people will go see movies like this. And especially given the time — it was a time where racial issues are very much on the minds of all Americans. We've just come through the civil rights era. By the late ’60s, urban rebellions happen almost every summer in big cities and small towns throughout the United States. So, race was a thing. The audience that went to see “The Learning Tree” was undoubtedly very much like the audience for Life Magazine: middle class people who were concerned with a serious movie. “Shaft” made a lot of money, too. And once again, it was a mixed audience. It wasn't just African Americans who were going to see “Shaft.” I think a lot of young white people also went to see it.

It's similar in the way that hip-hop did not survive on just the African American audience. Right? It's lots and lots of white kids in the suburbs who are into hip-hop and have been for the last 40 years.