Twenty years ago this week, the United States invaded Iraq, costing trillions of dollars and hundreds of thousands of lives.

Although most fighting is over, the legal basis for the invasion is still technically in force and 2,500 troops are still in Iraq.

A legislative effort to repeal the authorizations for the use of military force in Iraq is being cosponsored by Sen. Tim Kaine (D-VA). In the Senate, it could go to a vote next week, after passing through a committee earlier this month. In the House, Rep. Abigail Spanberger (D-7th) is also sponsoring legislation to repeal the AUMF.

One hundred eighty-five Virginians died in the Iraq war between 2003 and 2014, according to the Library of Virginia. Brown University’s Costs of War project estimated that about 300,000 people died during the war, including about 200,000 civilians.

The estimated cost of U.S. military operations in Iraq and Syria is $1.79 trillion, according to the Brown report. The researchers also considered military operations in Syria from 2014, when the military targeted the Islamic State group with Operation Inherent Resolve. IS, ISIS in popular parlance, traces its roots to Iraq in 2004.

Those costs will continue to go up, said Daniel Gade, Virginia’s Commissioner of Veterans Services, who is tasked with connecting veterans to benefits.

“Spending on veterans benefits related to the Vietnam War only peaked a couple of years ago,” he said in an interview. “We can expect the echoes of the war in Iraq, the war in Afghanistan, the global war on terror, we can expect those echoes for the next 60 or 70 years, really.”

The researchers at Brown estimated that the total obligations for veterans’ care until 2050 would be $1.1 trillion.

There are 671,519 veterans in Virginia, according to the Census Bureau, and a quarter of veterans nationwide served after 9/11.

Gade said many who served in Iraq and Afghanistan have experienced mental health issues. He cautioned against stigmatizing or othering them and said they need health care.

“They saw things on the battlefield, they did things on the battlefield, they had things done to them on the battlefield that have continued to affect them and their families since then,” he said. “Those people are struggling, and we need to get those folks the help they need.”

Gade didn’t want to speak for others, but he said his experiences serving in Iraq made him more skeptical of government.

“I was very seriously wounded and ended up losing a leg at the hip, and I sometimes wonder, was my sacrifice wasted? I struggle with that a little bit. I think about it a lot,” he said.

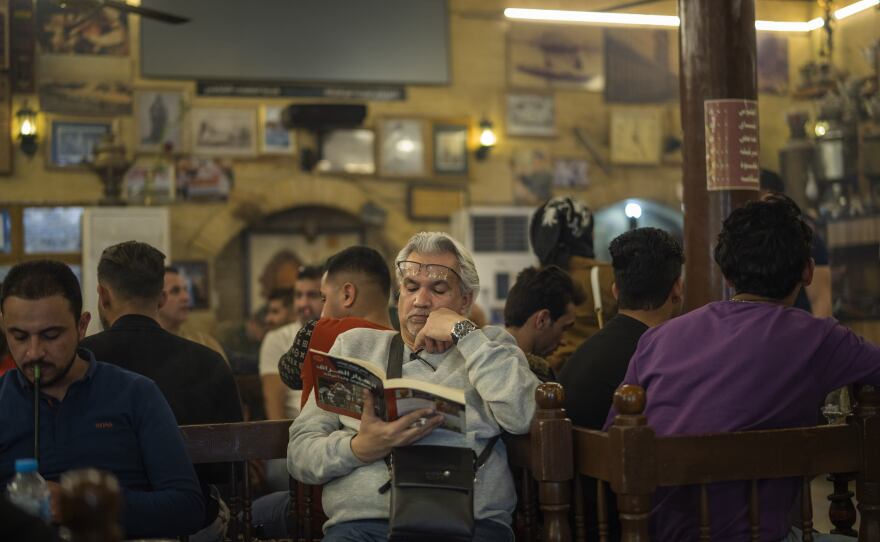

Loss, waste, and pain — those words also came up when talking to Iraqis who were forced to flee after the invasion as sectarian violence between political and religious groups mounted .

“Not leaving meant that we will be dying in a way or another. And we know that, and we remember that,” said Farah Ibrahim, who lives in Charlottesville and works for the International Rescue Committee. She and her husband Mahmoud Dawoodi were working at an Iraqi university in Baghdad when the U.S. invaded.

“At least personally, I feel guilty about the other people that we left that they didn't join us,” she said.

The Brown University researchers reported 9.2 million people were displaced due to the war. The International Committee of the Red Cross estimated about 15% of Iraqi people now have a disability.

“I'm trying to forget what happened because our life changed forever,” Dawoodi said.

He described starting a new life as relearning everything, as opposed to just adjusting. Americans’ relationship to work, the lack of Iraqis around his family and the language all pose challenges.

“Sometimes, I have to google the terms and find out ‘what's that mean?’” Dawoodi said. “If like insurance bill is coming, I want to know what's in the fine print. There's a lot of things we still want to learn.”

The couple have an acute awareness of the pain their friends and family feel because of their own experience with loss, particularly from the sectarian violence that accelerated in the early years of the American occupation.

Dawoodi’s father died in sectarian violence. And Ibrahim talked about her brother, who died in sectarian violence after his name gave his sect away. Ibrahim was pregnant at the time, so she experienced his death as a mother, she said.

“Imagine like a mother naming her child and knowing after she lost him, that naming him had caused her to lose him,” she said. “That's never goes away.”

A few months after her brother’s death in 2006, Ibrahim moved to the United States with her four-month-old daughter. Ibrahim said it was crushingly difficult to share what Iraq was like with her daughter.

“Everything she has been exposed to about where she came from, where she was born, is negativity — and sadness,” Ibrahim said. "There was no opportunity to put that idea of the life that we at least were introduced [to] or learned about, about what it means to be an Iraqi versus someone from another country.”

Ibrahim said she doesn’t know how to get that opportunity back.