Read the original story form the Virginia Center for Inversitgative Journalism at WHRO.

On the bright afternoon of Oct. 27, 1998, a civilian pilot and his crew of two were on final approach in their experimental Learjet to the NASA Wallops Flight Facility on Virginia’s Eastern Shore. The crew had been testing a new nose wheel tire for certification by landing through a long pool of shallow water on the runway.

Though they had made 10 successful landings the day before, on this attempt, the plane strayed a little too far to the right. On touchdown, the right wheels grabbed the dry pavement outside the pool while the nose wheel and left wheels splashed through the water. The pilot lost control, and the aircraft hydroplaned across the tarmac and off the runway. Spectators dodged the runaway plane before it hit an empty pickup truck, snapping off the plane’s wings and sending what was left rolling and spewing flaming jet fuel.

Aircraft rescue firefighters arrived and pumped water on the inferno, but to little avail, according to the Federal Aviation Administration investigation. The intense blaze, fueled by the high-octane jet fuel, continued to rage. Firefighters then doused the wreckage with firefighting foam, finally extinguishing the fire.

Remarkably, the pilot and crew safely evacuated the plane with only minor injuries.

But the enduring damage from the mishap had just begun. Twenty-five years later, the quiet fishing village of Chincoteague is still grappling with the consequences of the toxic chemicals used to extinguish the blaze.

Chincoteague sits just a few miles away from Wallops, across the Queen Sound Channel and Mosquito Creek. Famed for its oysters and wild ponies, the town draws water for its roughly 3,300 residents from wells that sit within eyesight of the 1998 crash on NASA property. For decades, the toxic chemicals found in Aqueous Film Forming Foam, which was used to fight the fire from that crash, have been seeping into the town’s well water, which serves its businesses, schools and homes.

It wasn’t until the conclusion of a 2017 base-wide water study, requested by the American Federation of Government Employees Local 1923 union, that residents learned of widespread contamination caused by the firefighting foam’s toxic PFAS chemicals.

The environmental study found that the PFAS levels in the town’s drinking water greatly exceeded the Environmental Protection Agency’s nonbinding regulations for lifetime exposure.

Military and town officials faced a costly dilemma: how to purify and provide clean, safe water to the community. The answer was a $2.5 million water treatment system that came on line in April 2021.

But the uncertainty of the pollution’s long-term health effects still weighs on many of the town’s residents.

“You never really know when the end of it is going to be,” said Hunter Leonard, a firefighter and lifelong Chincoteague resident. “It is kind of a great unknown.”

The residents of Chincoteague are not the only ones in the commonwealth facing this unknown. Several Virginia communities are starting to identify and address the potential threats of drinking water tainted with the same toxic chemicals found in that firefighting foam. New rounds of water testing have discovered elevated levels of these chemicals — which have been linked to cancer, thyroid disease and numerous other ailments — in drinking water sources from Richmond to Abingdon and Northern Virginia to Norfolk.

The chemical industry and military, state and federal agencies have known for decades about the dangers of these widespread chemicals, but strong federal regulation is only now appearing on the horizon. On March 14, the EPA announced that it would begin the process of regulating certain types of PFAS.

Virginia has only recently begun more extensive testing for the toxins. In 2020, Virginia’s legislature allocated $60,000 to investigate PFAS contamination — an amount environmentalists say is well below what’s needed.

The effort has fallen to two resource-strapped state agencies — the Virginia Department of Health and the Department of Environmental Quality — and mitigation efforts are proving costly. Experts say it could create a heavy economic burden for decades to come.

“It’s important for communities to question what’s in their drinking water,” said Carroll Courtenay, staff attorney for the Southern Environmental Law Center. “There's just no reason we should be waiting for a public health disaster before taking serious steps.”

The ‘forever chemicals’

PFAS, an abbreviation for perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances, were first developed by manufacturing giant 3M in the 1940s and ’50s. The virtually indestructible substances are so stable that scientists call them “forever chemicals.”

Because of their composition, PFAS slide through the earth and into aquifers with ease. If they're discharged into the air, they can be carried by the jet stream for miles. Their elegant chemical structure and properties made them perfect for many uses, including fire suppression.

In collaboration with the Navy, 3M created Aqueous Film Forming Foam to fight the intense blazes caused by jet fuel spills. The product was so effective, it was sold to military and civilian airports around the world. In Hampton Roads, the Navy routinely practiced fire suppression drills on ships, discharging hundreds of gallons of the chemicals at once and washing the sudsy liquid into the Elizabeth River and Little Creek. Roughly the same scenario played out at military airports and ports as well as several commercial airports around the state for decades.

The military announced in January it would stop using foam with PFAS.

Because PFAS soon found their way into nearly every facet of daily life — nonstick cookware, food packaging, clothing, pretty much anything that could benefit from being water- and grease-resistant — the toxic chemicals also found their way into humans. A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study from 2007 found PFAS in more than 98% of the population. Subsequent studies have found them in fetuses and breast milk.

While two of the most commonly used versions of the chemicals, PFOS (perfluorooctanesulfonic acid) and PFOA (perfluorooctanoic acid), have largely been phased out in the United States, the chemicals remain widespread in water and soil. There are also, by some estimates, as many as 10,000 other variations in existence.

In 2016, the EPA instituted a nonbinding lifetime health advisory of 70 parts per trillion combined for PFOS and PFOA. For reference, 1 part per trillion is equivalent to one drop of water in 20 Olympic-sized swimming pools.

Last June, the EPA significantly lowered the lifetime health advisory at which it considers the chemicals safe to ingest to 0.004 parts per trillion for PFOA and 0.02 parts per trillion for PFOS.

“This is the amount that you can consume daily where it is not going to increase your health risks over the course of your lifetime,” said Melanie Benesh, spokesperson for the nonprofit Environmental Working Group, noting that the advisory is simply a recommendation and not an enforceable standard.

Unlike mercury, lead and asbestos, PFAS aren’t regulated by the EPA. But that may be about to change. The new EPA proposal, if finalized, would regulate levels of PFOA and PFOS compounds in drinking water at 4 parts per trillion, a level at which the chemicals can be reliably measured.

“EPA’s proposal to establish a national standard for PFAS in drinking water is informed by the best available science, and would help provide states with the guidance they need to make decisions that best protect their communities,” said EPA Administrator Michael S. Regan. “This action has the potential to prevent tens of thousands of PFAS-related illnesses and marks a major step toward safeguarding all our communities from these dangerous contaminants.”

What’s in Virginia’s water?

Despite decades of recorded PFAS use in Virginia, it wasn’t until recently that the Virginia Department of Health began to seriously investigate the scope of these toxic chemicals in the state’s drinking water.

Tony Singh, a former environmental engineering manager at the University of Virginia, was hired by the Department of Health in 2019 as deputy director of the Office of Drinking Water. Shortly after starting, Singh petitioned his supervisor to begin looking into PFAS contamination.

A lobbying effort by public health officials in 2020 helped persuade lawmakers to pass a pair of bills studying PFAS contamination. The two measures, HB 586 and HB 1257, requested that the Department of Health set a lifetime health advisory equal to or lower than federal guidelines for PFAS. It also instituted a working group to survey how prevalent the chemicals were.

In 2021, the health department began a small study, sampling 45 of the state’s roughly 2,800 water systems. The study, released in September 2021, found that no systems exceeded the EPA’s recommended limits in place at the time. However, at least a quarter of the systems would fail to meet the new, tighter advisories released by the EPA two months later.

The PFAS working group recommended lawmakers allocate more funding for sampling and that the Department of Health consider creating its own regulations for acceptable PFAS levels similar to those implemented in more than a dozen other states.

“We talked through what we thought might be needed to get a better, fuller picture,” said Anna Killius, advocacy director for the James River Association environmental nonprofit and a member of the working group. “And it was $600,000.”

So far, however, the General Assembly has dedicated only 10% of the working group’s recommendation for further testing.

The Department of Health was able to supplement the $60,000 allotment with $142,300 in funding from the EPA to test Virginia drinking water for PFAS.

Early testing in 2021 revealed some surprising results from the seemingly crystal waters of the South Fork of the Roanoke River. Samples from the Western Virginia Water Authority showed elevated levels of GenX — a newer form of PFAS designed to replace PFOA — from the Spring Hollow reservoir. The 3.2-billion-gallon reservoir serves more than 69,000 customers across the Roanoke Valley.

A sample taken at Spring Hollow returned a relatively high level of GenX at 51 parts per trillion. A follow-up test came in at 57 parts per trillion, according to the health department.

The EPA’s new standards, released in June 2022, noted that exposure to GenX at more than 10 parts per trillion can have negative health effects.

Aware of the new federal guidelines, the Western Virginia Water Authority stopped pumping water out of the river and into the reservoir in August. It also began using a granular activated carbon-filtering system to remove the GenX chemicals.

After filtration, GenX levels in the resevoir water dropped to safer levels, but in early November, a test of river water by the state Department of Environmental Quality and the Western Virginia Water Authority came back with an eye-popping 1.3 million parts of GenX per trillion.

The probable sources of the contamination, according to the state, were the Ellison wastewater treatment plant and an industrial water treatment company called ProChem.

ProChem is upriver from where the authority draws its water.

In a statement to The Roanoke Times, a ProChem vice president said any discharge that may have come from its plant was accidental and the company has fully cooperated with local and state water officials to treat the problem. Since GenX is not regulated by the EPA, the ProChem vice president said the company’s routine testing would not have discovered its presence.

The state Department of Environmental Quality is still investigating the GenX release. ProChem did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

“Our mission is to make sure that we deliver a good drinking water product to our customers,” said Sarah Baumgardner, a spokeswoman for the Western Virginia Water Authority. “We’re stewards of the Roanoke River.”

An overlooked reservoir: private wells

Outside the entrance to the Fentress Naval Auxiliary Landing Field in Chesapeake, Boun Keosavang walked past a pyramid of empty 10-gallon water jugs on the ground beside his daughter’s scooter and into the carport of the home he and his family have rented for more than a decade.

In the back of the garage, Keosavang moved a couple of loose boards to inspect the home’s water filtration system. It was installed by the Navy in 2017, shortly after it discovered that the household well water exceeded the old EPA health advisory of 70 parts per trillion for PFAS.

More than five years later, the Navy still supplies his family and several other homes nearby with bottled water and carbon-filtering systems.

“They said it was some chemical they used to put fire out and it got into the ground, into well water,” Keosavang said. “It’s good water now, from what I see to the naked eye. But I don’t know anything that’s microscopic. I don’t know what to look for, so I’m trusting them.”

The Army, Navy and Air Force have recognized PFAS as an environmental hazard at installations in Virginia, especially airfields and auxiliary landing sites. Early screening of areas around suspected PFAS hotspots outside military airfields, including Fentress and Oceana Naval Air Station in Virginia Beach, revealed that water in several private wells had PFAS levels that exceeded the EPA’s original lifetime health advisory of 70 parts per trillion.

In 2016, the Navy began supplementing households with bottled drinking water and centralized community spigots from safe drinking wells. In a few cases, it installed household carbon filters that it services about once a year, according to residents.

Keosavang’s well is monitored by the military. But most Virginia residents using well water are on their own when it comes to checking for contamination, because it falls outside state and federal regulation.

More than 1 million Virginia households rely on private wells.

But until recently, there has been very little research on the PFAS contamination of private wells around the state, or the country, said Leigh-Anne Krometis, an environmental engineer and associate professor at Virginia Tech.

“I had heard, if you look for it, you will find it,” she said. “And I knew that if you’re detecting it in public waters, which are treated and monitored, you’re absolutely going to detect it in private waters, which are generally not treated or monitored.”

Virginia Tech researchers received a grant in November 2021 to test wells across the state and began with a small number in Floyd and Roanoke counties. Initial testing in 2022 found elevated levels of PFAS in roughly one-quarter of the wells, Krometis said.

“The proposed health advisory levels are very, very low, and we did not detect any shockingly high numbers,” she said. “I can throw science terms at you, but the person just wants to know, can my kid drink this water?”

Krometis hopes the study, once completed, will show where the toxins come from and how they get into the water supply.

At another home within eyesight of the Fentress landing field, Samuel Jones pulled his white pickup into the driveway of the house he’s lived in for about 40 years.

A few years ago, a broken well pipe forced him to dig a new, deeper well into a different aquifer system, he said. Recent PFAS tests haven’t shown any chemicals in his water, but he’s still concerned about the long-term impact.

“You’re not going to clean up the chemical when it is that deep in the ground,” Jones said. “Once it’s in the water stream, it is everywhere.”

Jones said he hopes the city of Chesapeake and the Navy will eventually run city water out to the area he lives. Navy spokesman David Todd said the service has awarded a contract to hook up homes with contaminated wells outside Oceana Naval Air Station to city water by 2025. But he said the Navy is still working with the city of Chesapeake for a permanent solution outside Fentress.

Heavy future costs and uncertain funding

In a large, corrugated building just east of the Wallops Flight Facility, NASA restoration program manager David Liu unlocked a set of tall double doors to reveal four hulking, black, pill-shaped containers. The containers make up two filtration systems, each filled with 5 tons of granular activated carbon.

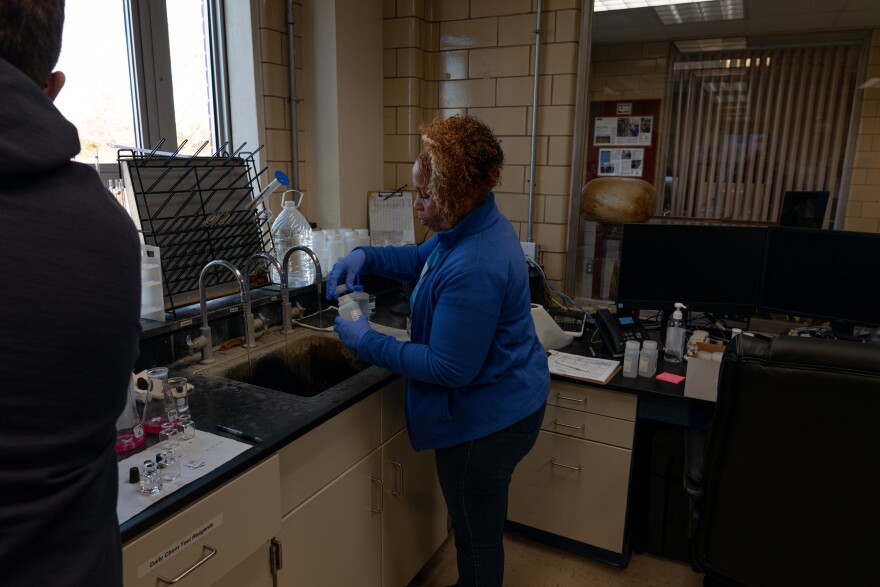

Chincoteague’s tainted water is drawn from several wells nearby and pumped to a central station before entering the remediation building. First, heavy metals are filtered out, then the water moves through the carbon filters, which clean out PFOS and PFOA, before flowing to a second filter where other chemicals are captured before the finished drinking water is sent toward town.

The system can filter about 410 gallons per minute and includes a backup unit.

“We monitor the system on a regular basis, at least monthly, sometimes biweekly, to track the treatment progression,” said deputy division chief T.J. Meyer of the medical and environmental division at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. “And what we found through our extensive monitoring is that the carbon is very effective in removing [PFAS] to the lowest levels detectable.”

The new filtration system has helped ease community concerns, but questions remain.

Firefighter Hunter Leonard, son of the current Chincoteague mayor, was 2 when the plane crashed at Wallops.

“The first instinct by people is to go and look up what is happening,” Leonard said. “What is PFAS? What is firefighting foam? What potential harm can it cause? And you see these things like cancer-causing agents. So, you naturally begin to worry. I kind of drew up my own conclusion saying, well, I’ve lived for 20 years and I don’t have any long-term effects.”

Liu said with monitoring and testing, the Wallops plant costs about $400,000 a year to maintain. NASA would like to find a long-term solution that is less expensive, Liu said.

The long-term costs of carbon filtration systems — including millions in infrastructure costs and ongoing expenses for purchasing and disposing of the carbon — could make it impossible for many small- and medium-sized water authorities to afford on their own, said Singh of the Virginia Office of Drinking Water.

In 2021, Congress included $10 billion to combat PFAS contamination. Half the funding is dedicated for grants to small or disadvantaged communities.

Singh said Virginia will receive about $12.5 million annually for water infrastructure at local water authorities to take care of emerging contaminants, including PFAS.

“We need to both give people comfort that we understand the situation,” said Killius of the James River Association, “and tap into those federal resources that waterworks are going to need to solve the problem.”