Read the original story on WHRO's website.

Locals hear it year after year: Norfolk has the highest rate of sea level rise on the East Coast. But that’s not only from rising waters. It’s also the land beneath us slowly sinking.

New research out of Virginia Tech suggests officials need to start focusing more on the latter.

It found that land in Hampton Roads is sinking at about twice the rate that waters are rising.

The study, which calls the issue a “hidden vulnerability,” was published recently in the journal Nature Communications.

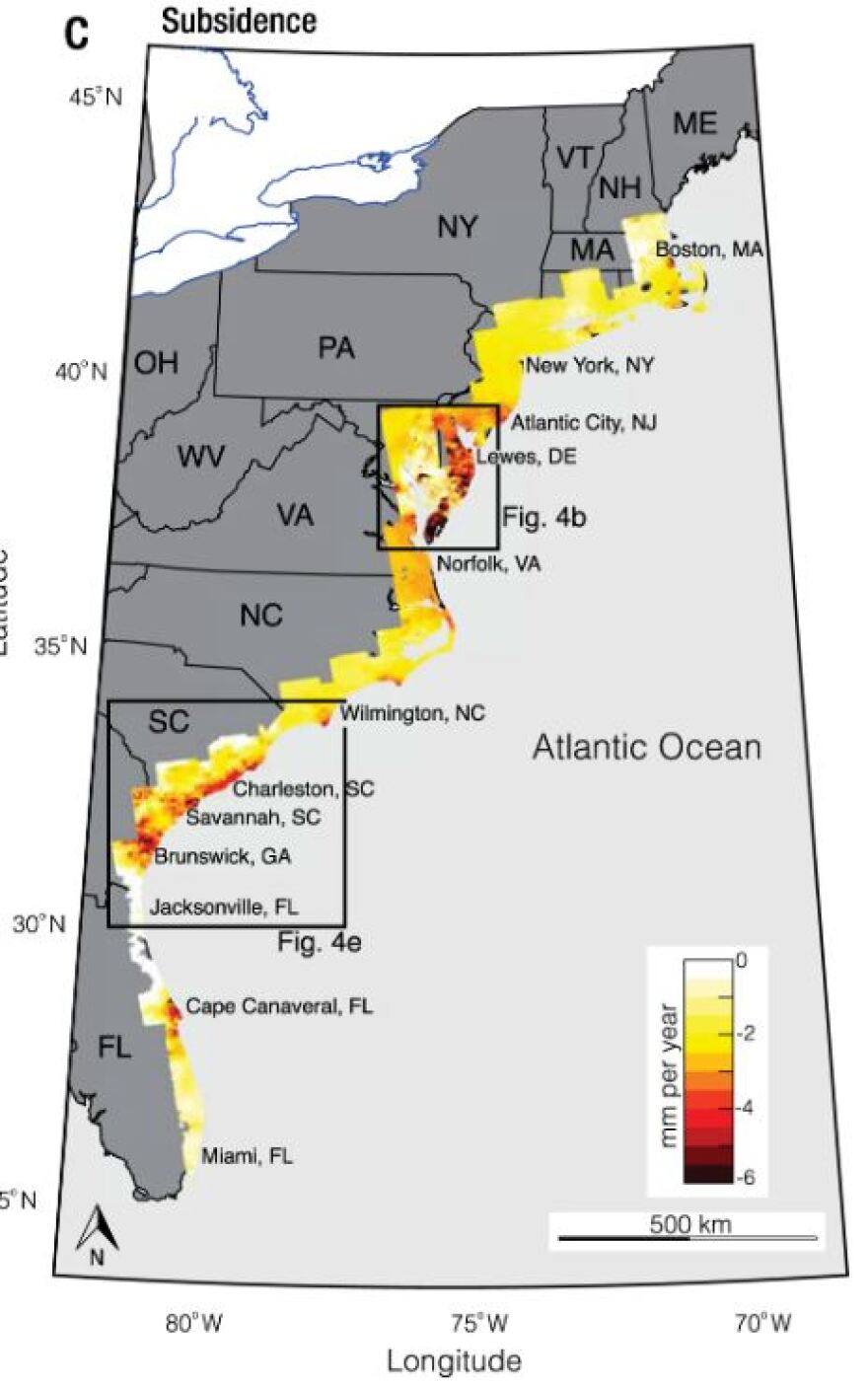

Researchers in Blacksburg used satellite data to precisely map out rates of subsidence — the term for gradual sinking of land — across Atlantic coastal areas between 2007 and 2020.

It happens for a number of reasons. Part of it is the earth’s natural response to glacial forces from thousands of years ago, adjusting to the retreat of great ice sheets that once covered the surface, according to NASA.

For the same reason, some areas are actually rising, a concept known as uplift.

That’s not the case in southeastern Virginia, though. NASA points to the Chesapeake Bay region as experiencing high subsidence rates that contribute to vulnerability from sea level rise.

Over time, sediments in the bay loosen and strain under the pressure of more layers, a process called compaction that also contributes to subsidence.

Humans are behind another big driver: withdrawing groundwater faster than it can be replenished.

Officials hope one local project can start reversing that, albeit slowly. The Hampton Roads Sanitation District has been pumping a million gallons of treated wastewater each day back into the local aquifer.

Manoochehr Shirzaei, associate professor of geophysics and remote sensing at Virginia Tech and co-author of the new study, said research to date about subsidence along the Atlantic relied on a limited amount of data — from just one type of satellite, say, or over a short time period.

His team combined multiple datasets over more than a decade to reduce uncertainty.

“This is the first measurement that provides accurate observation of the vertical land change in [the] Chesapeake Bay,” Shirzaei said. “And using those datasets, we could tell which parts of the Chesapeake Bay [are] going to be flooded in the course of the 21st century.”

The bay region is a hotspot for the issue. It’s also home to the world’s largest naval base, a large population and several Indigenous tribes, he said, making it important to know how climate change and subsidence will interact in the decades to come.

The global average rate of sea level rise is about 3.3 millimeters per year. In parts of Hampton Roads, land is sinking by as much as 6 millimeters.

Put those together and the region can see more than 9 millimeters of annual land loss.

Those numbers may sound small, Shirzaei said. But over time they can have a drastic impact.

“Effectively, land that's at the moment above the water will be submerged within a few decades,” he said. “The hazard that people would experience actually is mostly due to the land subsidence, not sea level rise itself.”

The study authors wrote that in some places along the Atlantic coast, impacts of sinking land “could be ten times greater” than that from global sea level rise.

The researchers also say previous studies substantially underestimate the vulnerability of coastal marshes and agricultural lands to subsidence.

Boston; New York; Charleston, South Carolina; and Lewes, Delaware, are among the cities most impacted, along with Norfolk.

Shirzaei said he hopes local officials will start incorporating the issue more within ongoing conversations and policies about sea level rise.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, for example, talks about subsidence only marginally, he said.

But communities will need help adapting to looming landscape changes. Waiting for the worst impacts “would be too late to do anything to mitigate that.”