Last summer, Teenora Thurston’s friend called her to help with a flat tire. They both live in Gilpin Court, a public housing complex in Richmond’s Northside.

Thurston, an organizing fellow with the Legal Aid Justice Center — a grassroots anti-poverty organization — said she saw a man working on what she thought were solar panels.

“I’m nosy, so I ask questions,” she said. “I was like, ‘What’re you doing, sir?’”

The man told her he was putting up cameras.

“I said, ‘We got enough cameras up,’” she told VPM News on a recent tour of Gilpin to see surveillance equipment placed around the properties. “He said, ‘Well, these some different cameras.’”

The cameras are license plate readers, a powerful piece of technology used to track a vehicle and a person’s movement. Officials with the city of Richmond accepted a grant from the state earlier this year to add 30 license plate readers as part of a more robust surveillance network that could allow the Richmond Police Department to centralize its police technology into a real-time crime center.

What is a Real-Time Crime Center?

RTCCs vary across law enforcement agencies, and Richmond is in the phase of planning and procurement. As an RPD spokesperson said in an email, the process will consider what sort of “real-time technology solutions” are appropriate for the city. Documents indicate that the city has requested funds for specific surveillance equipment.

Generally, RTCCs centralize different information or surveillance feeds law enforcement have. Their utility comes from the “real-time” aspect: Not only are existing police technologies fed into a command center, but many more feeds can be made accessible through agreements with other government and private entities.

“Kind of like the Starship Enterprise, it’s a room that’s got a lot of TV screens,” said Newport News Police Chief Steve Drew, whose department has a RTCC he said RPD officials have visited. Drew gave examples of looking at camera feeds in schools and hospitals after emergency calls.

Documents obtained by VPM News show in November 2022, RPD applied for a grant from the Virginia Department of Criminal Justice Services for real-time crime infrastructure. It wrote that $750,000 for training and equipment would reduce violent crime and support RPD’s response to violent crime.

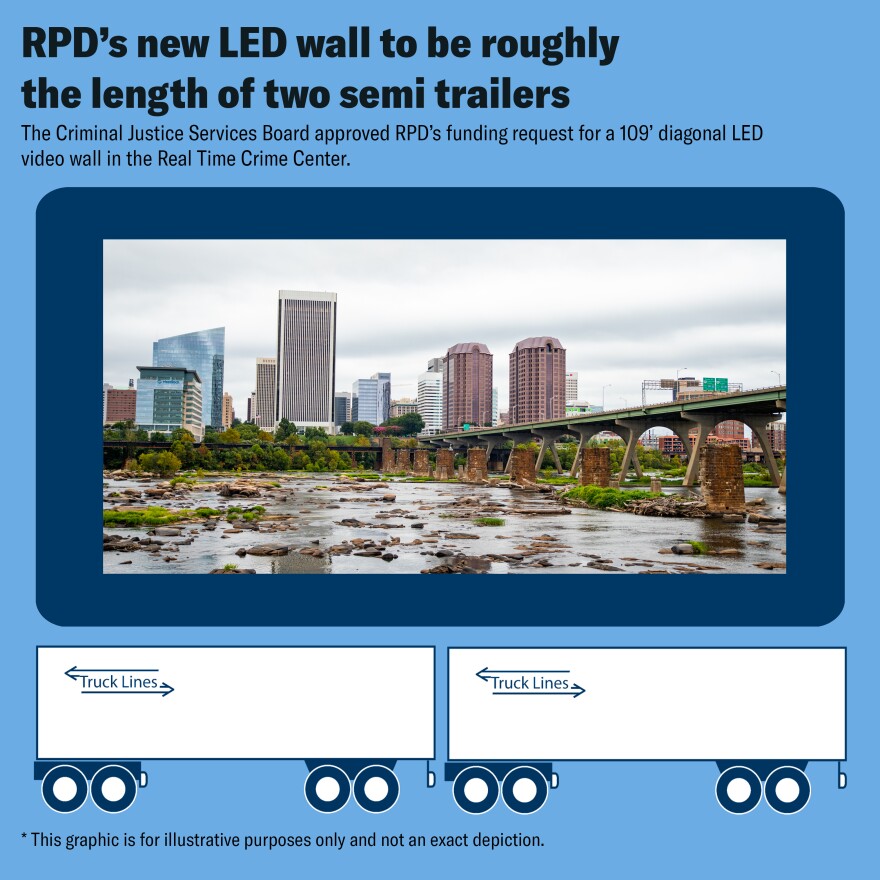

The city’s application included funding for a 109-foot LED wall, which is roughly the length of two semi-truck trailers, that could be flexible to display the expanding capability of the police department.

“Richmond is pretty sophisticated,” said Will Pelfrey, a criminal justice professor at Virginia Commonwealth University, who said he’ll be part of a team evaluating Richmond and other RTCCs over the next year. Pelfrey listed ShotSpotter, a gunshot detection system, cameras tied to VCU and other private and public camera feeds.

“Most red lights have a camera. Lots of tollbooths have cameras and tollbooths also have license plate readers. Banks often have cameras. Parking lots have cameras. So there are public and private video recordings happening all the time,” he said. “Those can be seamlessly tied to Richmond Police Department. Then RPD has thousands of video feeds that they can access at any given moment.”

The Richmond Police Department itself has at least dozens of camera feeds, according to a FOIA request. It declined to release the locations of some cameras, claiming it would compromise investigative capacity. Many are at police facilities, but others are spread across Richmond, such as in Shockoe, Whitcomb, the Fan and Jackson Ward.

In responding to a records request from VPM News, RPD sent an incomplete list of camera locations it operates. That list included 58 cameras, which are numbered 5 through 164.

The $750,000 DCJS grant, which used funds from the American Rescue Plan Act, included funding for 30 cameras like the ones Thurston saw in Gilpin Court.

It also named other powerful surveillance technologies — including Fog or Cobwebs technology that allow investigators to identify cellular devices in an area without a warrant via purchasable advertising data — and $125,000 for software from the Georgia-based company Fusus.

Fusus offers different technologies for real-time crime centers, including products that centralize video feeds, and another that allows for private video feeds or networks to be connected to RTCCs. VPM News submitted public records requests for drafts of requests for proposals or solicitations for software for a real-time crime center. RPD responded with several key pieces of information about its RTCC proposals and plans, but RFPs were not among the documentation provided.

VPM News reached out to several large government and public-private institutions to see what camera-sharing agreements exist in the city. Richmond Redevelopment and Housing Authority, Virginia Capitol Police, VCU and VCU Health all have not explored memoranda of understanding with RPD in connection with the potential RTCC, according to various spokespeople.

Richmond Public Schools is currently reviewing its camera-sharing agreement with RPD, and declined to say how many cameras the school division has. If any were to sign a camera-sharing agreement, their camera networks would likely provide RPD with surveillance coverage over much of the city.

The surveillance potential of a real-time crime center for Richmond expands into police technologies, such as facial recognition and artificial intelligence. Those present specific risks, says Beryl Lipton, an investigative researcher with advocacy organization the Electronic Frontier Foundation.

“People have this idea that algorithms and computers are objective,” said Lipton. “And that's just not true.”

Richmond Police mentioned its predictive policing trial, Operation Red Ball, in its grant application. That program led to the arrest of 45 people in 2022.

Can technology address policing challenges?

RPD is setting up the new real-time crime center amid two large challenges for the department: a series of community trust incidents and difficulty in maintaining staffing at funded levels.

In July 2022, the police retracted statements surrounding unnecessary use of force on peaceful protesters in 2020 after settling a lawsuit. Shortly afterward, the former police chief claimed officers had foiled a mass shooting plot at the Dogwood Dell Amphitheater, before reporting showed he did not have evidence of the shooting location.

The Legal Aid Justice Center’s Thurston is skeptical of arguments that using technology rather than officers means fewer opportunities for bad interactions with the police.

“It won't go well, because it's already a trust issue,” Thurston said, characterizing police interactions in Gilpin as aggressive, overly formal and generally lopsided. “As far as the police, they don’t approach with good intent.”

She claimed she hasn’t seen the police patrol Gilpin Court on foot in years, raising questions about how much police interactions could be reduced by utilizing tech.

Richmond Police command staff has been conducting community "walks and talks" throughout the city. The DCJS grant mentioned foot patrols and community policing as a possible response to concentrated crime.

Workforce issues also appear to be driving much of the city’s push for using RTCC technology.

“We are unfortunately experiencing a roughly 150-officer shortage at the moment. And even though we've seen an increase in applications in the past quarter, we're still dealing with a lack of hands to do the job,” said Mayor Levar Stoney on Aug. 3. “How do you replace individuals who are walking the beat or who are patrolling certain areas? You have to replace that with technology and innovation.”

Lipton from the EFF says companies selling real-time crime technology are aware of staffing concerns.

“You're going to see this phrase ‘force multiplier’ used in all sorts of marketing materials, because that really strikes a chord with these police departments. They feel pressured and understaffed,” she said. “If there's a technological solution to dealing with that, that is going to be appealing to them as a consumer.”

Drew of the Newport News Police Department said the tech was a “force multiplier” for quick actions and gathering evidence for use in the judicial system. He also said it could help his department “stem the tide” of retention issues.

The same volume of information police sees as an asset, Lipton sees as a civil liberty liability.

“We're at this point where technology has really challenged what the average expectation of privacy is not in a good way,” she said. “Because of technology and because of the way that is proliferated, outpacing regulation, we have sort of this shift that we, I think, as a society kind of need to course correct on.”

How the technology can be audited — to check whether surveillance is being abused in an investigation or abused for officers or staff’s personal use, is also a consideration for policymakers. Some RTCC software allows for police to access the same information on mobile devices, though it is unclear whether that will be among RPD’s “real-time technology solutions.”

City Council President Michael Jones cut off VPM News when a reporter asked about the real-time crime center at an Aug. 3 press event, questioning the intent and appropriateness of the topic at an event for small, Black-owned business. Jones did not respond to a follow-up question about RTCCs by press time.

RPD didn’t answer a specific question on privacy or accountability concerns, but Stoney said Richmond Police Chief Rick Edwards and his team want transparency and safeguards for data privacy.

“The cost is not just the initial buy-in cost. It is also thousands and thousands of dollars, every year, in order to continue to use those services.“

What are the costs and benefits?

Pelfrey said that the centralized, live nature of RTCCs are particularly oriented to deal with ongoing, in-progress violent crime. Since those make up a smaller number of incidents it will be hard to determine their efficacy, he said.

“It’s going to take a long runway to really see how much difference they make,” he said. “The numbers where crime is really high are the discovery crimes, property crimes, vandalism, stuff like that low level property crime.”

According to Virginia State Police statistics, there were 857 instances of violent crime in Richmond in 2022, including 60 homicides. Property crimes numbered 12,094. Richmond’s grant application wrote that it would cover 17 of the city's 150 neighborhoods but did not specify them by name.

In St. Louis, a real-time crime center’s camera network was more heavily concentrated in business districts and not in areas with violent crimes, according to St. Louis Public Radio. Local criminal justice advocates in Richmond have long argued that policing preferences property, citing the history of slave patrols and anti-union activity.

Lipton said communities like Richmond need to debate the costs and opportunity costs of an RTCC: “The cost is not just the initial buy-in cost. It is also thousands and thousands of dollars, every year, in order to continue to use those services. And that really, really adds up.”

DCJS grant applications included a line item for Fusus technology, ranging from $6,250 a month in Danville to $16,667 a month in Norfolk. (Richmond requested and received $125,000 for Fusus as part of its $750,000 grant.)

Where else are RTCCs being set up?

Richmond is not alone in the adoption of this technology, in the state or across the US. At least eight other localities won funds for their existing or development of real-time crime center alongside Richmond in this round of DCJS grants. Danville, Hampton, Lynchburg, Martinsville, Newport News, Norfolk, Petersburg and Roanoke all mentioned “real-time crime center” or “real-time crime center reporting” in their funding applications.

Lipton and the EFF found 135 law enforcement agencies with or setting up RTCCs that either centralize video feeds or use Fusus. The pace of its spread accelerated in recent years, as cheaper technologies and more federal money became available.

“It would have been pretty difficult to do this without the American Rescue Plan dollars. I'm grateful for President [Joe] Biden and for Congress for investing in these sort of programs,” said Stoney.

EFF’s counted 17 agencies with or setting up real-time crime centers through June 2023. For all of 2022 it was 15 agencies, and there were 12 in 2021.

The relationship between technology and staffing races also could feed into one another, as localities use technology to woo the same pool of new police cadets and officers.

“So, when we interview some of the potential candidates to join the department, a lot of them will ask, ‘What kind of technology do you have?’” said Drew.

RPD considers technology to be integral to its mission. In its application for the RTCC funding, it said tech is “woven into every fiber of a police department.”