While the smoke has mostly cleared in Virginia since July, scientists are sounding the alarm that — with climate change heating up the world and creating drier conditions — smoky summers will grow increasingly common.

“We all woke up and couldn’t see across the street,” said Lucas Henneman, a George Mason University professor. “And we’re thinking, ‘Well, something needs to be done about this.’”

Henneman studies the impacts of air pollution sources on health. He's the co-author of an article about protection from wildfire pollution.

“We need[ed] to communicate to the public that A. This isn't normal, and B. There are things we could be doing to protect ourselves from this.”

Climate change and smoke

Along with the fires themselves, wildfire smoke has long been considered a West Coast problem. But with a handful of events in recent years, the fires, their smoke, their health impacts and their relationship to climate change have increasingly become a conversation in Virginia and across the East Coast.

Sean Sublette is the chief meteorologist at the Richmond Times-Dispatch. He spent two decades working as a meteorologist for TV stations in Southwest Virginia before focusing more on climate change in particular about 10 years ago.

Citing a new report from World Weather Attribution, Sublette reported last week that climate change more than doubled the likelihood of extreme fire weather conditions in Eastern Canada. Fires there went on to bring the smoky conditions Virginia has experienced.

Sublette says the warmer, drier weather caused by climate change exacerbates wildfires.

“It's a threat multiplier,” he said. “It doesn't necessarily cause something, but it tends to make it worse.”

Sublette cautions that the specific circumstances of this year’s smoke – which is largely from Canadian fires and a contributing north wind – won’t happen every year exactly like this. But that wildfire smoke is something Virginians will experience more often.

“If we're going to start seeing more wildfires, that means there's going to be more smoke. Smoke is what's really going to hurt people, right?” he said.

“Most of us can get out of the way of fire — but the smoke, you can't do much about that.”

Health impacts

These increasingly smoky summers have serious health impacts, according to Dr. Neelu Tummala, co-director of the Climate Health Institute at George Washington University.

The smoke contains a number of harmful small particles, which is dangerous for everyone and especially so for people with respiratory conditions like asthma.

“One of the major concerns with this fine particulate matter is that it can cause irritation and inflammation inside the lungs,” Tummala said.

Research from California has found wildfire smoke increased respiratory disease-related emergency department visits by more than one-fourth. The CDC found similar impacts from smoke on the East Coast this summer.

And it’s not just the respiratory system that is impacted.

Wildfire smoke contains particles less than 2.5 microns – or about 30 times smaller than the width of a human hair. “That ultra-fine particulate matter can also enter the bloodstream,” said Tummala.

Once in the bloodstream these particles, known as PM2.5, increase the risk of heart disease, high blood pressure, heart attacks and stroke.

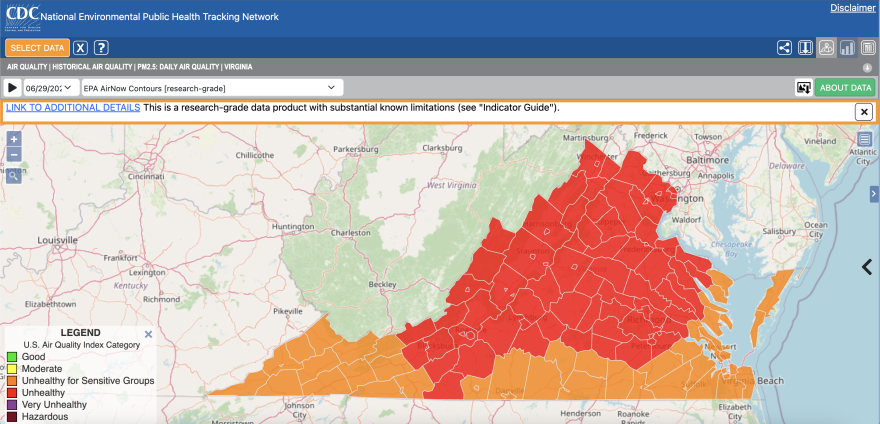

While the East Coast was blanketed in smoke during June and July, there were times when the majority of the commonwealth was covered in what the CDC considers an “unhealthy” level of PM2.5 particles.

Disparities in impacts

The impacts of this smoke aren’t divided equally, according to Tummala. Children, people 65 and older and pregnant people are at high risk. She also cautions that people who spend more time outside face particularly large risks.

“Anyone who has to spend extended periods outdoors,” she said. “So that's a lot of outdoor workers, that's construction workers, people who work in agriculture.”

Latinos are disproportionately represented in both construction and agriculture work, according to data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Tummala says poorer people are also over-represented in this group: “The reason that people of a lower income are at higher risk is because they may not be able to afford some of the adaptation strategies that we have to cut back the wildfire smoke. So whether that's air purifiers, masks to protect themselves while breathing, being able to stay indoors, things like that.”

People who work in those environments and can’t call in sick are also particularly impacted, according to Tummala.

How to protect yourself and recognize signs of health impacts from smoke

Henneman, the GMU professor, was shocked by some people’s response to the smoke.

“I looked out the window and people were running like normal. And I couldn't see that next house,” he said. “You don't want to shame people for making decisions, but we need to make sure at least they know that this is really bad for them.”

One key tool is checking air quality levels before going outdoors.

While not everyone can stay inside when it gets smoky, that’s the best thing you can do to protect yourself, according to Henneman

“I know from our research how dangerous really high air pollution days can be,” he said. “People should be behaving differently during days like that when the air pollution is really bad.”

For anyone who has to be outside, the EPA recommends wearing a well-fitted mask like an N95. And for people who work outdoors and/or experience respiratory difficulties, Tummala recommends a few extra precautions.

“Whether it's getting an extra inhaler, whether it's trying to do some saline rinses, whether it's being cleared to take extra breaks while you're at work or wearing a mask,” she said. “Any of those things will help keep you safe.”

Tummala also says anyone outside should also stay alert for signs of smoke-related health impacts like feeling short of breath or out of breath.

Other signs and symptoms include: increased cough, increased nasal congestion, mucus production, difficulty breathing, noisy breathing, sinus congestion, facial pressure, headaches and eye or nose irritation or itch.

Policy change needed

Tummala, Henneman and Sublette all stressed that while adapting to smoke and its impacts on your health is essential, at the end of the day, the only solution is fighting climate change by lowering local and global dependence on fossil fuels.

“Adaptation is very important, but I think the mitigation of impacts comes from addressing the root cause,” Tummala said. “The number one answer is reducing fossil fuel combustion. Wildfires have always happened but it's the more intensified wildfire seasons, the longer wildfire seasons, that are a particular concern as a clinician because we're seeing so many worsening health impacts from the wildfires themselves.”

And while that’s a global challenge, Henneman notes just as the rest of the world’s actions have an impact on us, our actions locally have an impact on the rest of the world.

“There's this link between policy here, climate impacts elsewhere and then health here.”

To him, addressing air pollution here can lead on some level to reduced risk of wildfires around the world, which in turn lowers Virginians’ smoke exposure.

Sublette, the meteorologist, points to green energy projects around the commonwealth and says there is hope.

“Fortunately, we are making progress,” he says. “We just need to keep moving the needle in the right direction and, I think most would argue, a little more quickly.”