Spotted lanternflies aren’t hard to spot: Around this time of year they’re in their adult form, about 1 inch long. They sport striking scarlet-and-tan wings with black dots and lines — and they’re continuing to spread across Virginia.

A new music video from the Virginia Cooperative Extension sums it up: It wants you to “Stop the Spot,” by stomping, squishing, spraying and scraping the invasive bugs away.

Eric Day is an entomologist at Virginia Tech, where he runs the insect identification lab and carries out pest surveys. He became aware of the spotted lanternfly (Lycorma delicatula) in 2014, when they were first identified in Pennsylvania. They went on to do extensive damage in that state, particularly to grapevines.

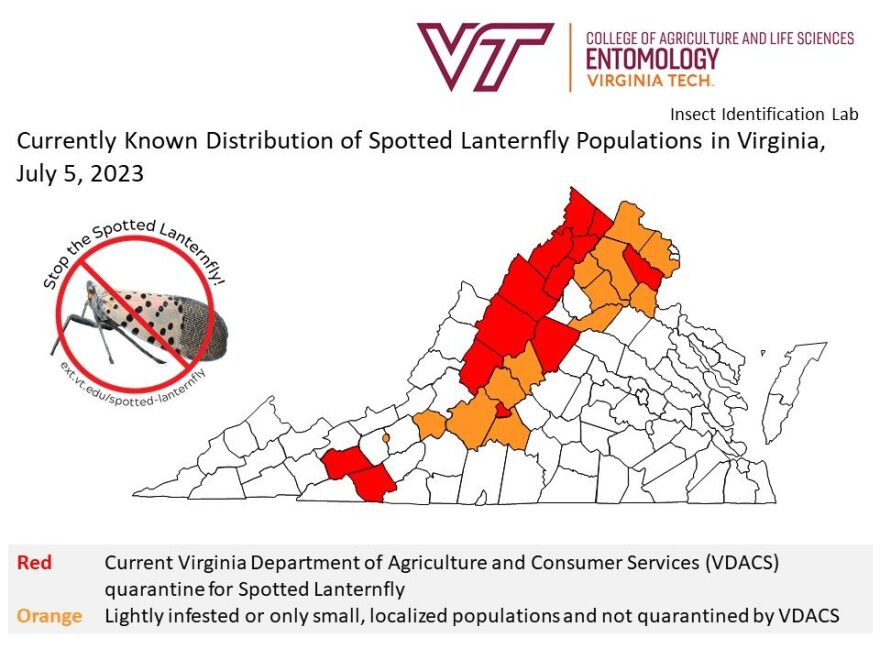

Day said Virginia’s first spotted lanternflies were identified in Winchester in 2018, near the northern tip of the state. Since then, they’ve steadily spread southwest, appearing near the state’s southern border in Carroll County.

“When you look at the maps, I think a lot of people say ‘that looks like a highway map or a railroad map,’ and in fact it is,” Day said.

That’s because the critters are great hitchhikers. They’re prone to attach themselves to trains or cars, disembarking at their destination.

And what is their destination? According to Day, they aren’t picky. There are about 40 species of plants in Virginia the bugs will use as hosts, which Day calls a “gut punch.” The planthoppers pierce into plants, sucking out the nutrients they need and leaving behind a sticky waste called honeydew, which can lead to molding. They’ll attack grapes, apples, hops and more.

But there is one plant that stands out as a preferred home.

“Tree of heaven,” Day said, “is an invasive species itself and grows predominantly well on disturbed soils like you find on long transportation corridors like railroads [or] highways.”

Trees of heaven grow quickly, outcompeting native species for sunlight and water. Their use in landscaping has introduced the trees to the wild. Like the mythological hydra, they’re notoriously hard to kill: If the roots are left living, they’ll sprout back up in multiple places. Day said the only viable method is herbicide.

So the bugs are good at spreading, and they have a premade highway system to usher them along, but the concern is not that they’ll find home in invasive trees.

It’s what those trees are near.

A threat to vineyards

Skip Causey found spotted lanternflies this summer at his vineyard, Potomac Point. They were the first of the species to be reported in Stafford County. And, sure enough — “We found one tree [of heaven] within about 50 feet of my one corner block that was bringing them in.”

He's also the president of the Virginia Vineyards Association, which advocates for Virginia's wine industry. Causey said he’s only found about 10 of the flies on his vines, which he’s killed with light pesticide application.

But he did find a stand of trees of heaven about a half-mile away. For now, he thinks that will distract the bugs from his grapes — as long as he can kill the nearby tree for good, all the way down to the roots.

Although the bugs are spreading rapidly, Causey is cautiously optimistic that lanternflies won’t have as heavy an impact on Virginia’s wine industry as Pennsylvania’s.

After the lanternflies were discovered there in 2014, things moved quickly. In some cases, vines were killed. Many more vineyards saw smaller, lower-quality harvests and long-term damage to their plants.

Now, Causey says it’s important to keep up with the pests like any other: Know the signs and respond quickly with pesticides, stomping and removal of host trees as necessary.

Quarantined counties

The state has also gotten involved in efforts to stop, or at least slow, the spread of the pest, setting up a quarantine system in 2019. The system is administered by the Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services.

In a statement to VPM News, VDACS communications director Michael Wallace wrote the “goal is to slow the rate at which spotted lanternfly spreads to provide more time for alternate control methods to be discovered and a better detection and monitoring tools are developed.”

Today, 22 localities are quarantined, including Albemarle, Augusta, Carroll, Clarke, Frederick, Page, Prince William, Rockbridge, Rockingham, Shenandoah, Warren and Wythe counties, as well as the cities of Buena Vista, Charlottesville, Harrisonburg, Lexington, Lynchburg, Manassas, Manassas Park, Staunton, Waynesboro and Winchester.

13 counties, including Stafford, have small infestations but do not qualify for the quarantine. Richmond, Henrico and Goochland all have reported infestations too.

Businesses in a quarantine zone must acquire a VDACS permit and perform inspections on “regulated articles” that will be transported out of quarantine. The department offers inspection training for $6.

VDACS has a long, inexhaustive list of regulated articles on its website:

- Any life stage of the spotted lanternfly;

- Live or dead trees; nursery stock; green lumber; firewood; logs; perennial plants; garden plants or produce; stumps; branches; mulch; or composted or un-composted chips, bark, or yard waste;

- Outdoor industrial or construction materials or equipment; concrete barriers or structures; stone, quarry material, ornamental stone, or concrete; or construction, landscaping, or remodeling waste;

- Shipping containers, such as wood crates or boxes;

- Outdoor household articles, including recreational vehicles; lawn tractors or mowers; grills; grill or furniture covers; tarps; mobile homes; tile; stone; deck boards; or

- Any equipment, trucks, or vehicles not stored indoors; any means of conveyance utilized for movement of an article; any vehicle; or any trailer, wagon.

Day said the quarantine protects companies shipping out of state — and offers some peace of mind to their customers. “Other states, other countries don't want it,” he said. "The receivers may request some type of permit or inspection sheet.”

What can you do?

To start, remember the song: “Stop the spot.”

Stomp and squish spotted lanternflies if you see them, spray if there are many or they’re infesting landscaping or crops, and scrape the egg masses, if you can find them.

The lanternflies live on a one-year cycle. Since they’re adults now, that cycle is coming to an end – which means it’s time for them to lay eggs. They lay eggs in masses, which are usually concealed under a glossy cover that fades to gray and brown over time, before cracking and sometimes falling away. Each mass can contain dozens of eggs, making them important targets throughout winter months.

The egg masses are found on all sorts of hard surfaces, often in protected places – under tree limbs or on outdoor furniture, according to a blog post by the Virginia Department of Forestry’s forest health manager, Lori Chamberlin. They’re more likely to be found around their preferred host, tree of heaven, or by areas with heavy vehicle traffic like rest stops.

When the spotted lanternflies begin hatching in spring, they have a different appearance as nymphs. Fortunately, they’re still striking: They start out all black and covered in white dots, before developing scarlet red markings.

If you find any of the bugs in a non-quarantined part of the state, don’t stop at stomping them: Take a picture or collect the critter and contact the local cooperative extension office.

The cooperative extension has information about the critter’s life cycle, range and identification tips available on its website.