Read the original story on WHRO's website.

At its mouth, Norfolk’s Lafayette River is about a mile wide, stretching from the former golf course at Lambert’s Point north to the Norfolk International Terminals.

This point, where the Lafayette meets the Elizabeth River, is currently a broad expanse of open water, dotted with sailboats on a sunny afternoon.

But by the end of the decade, the view will look a bit different. Norfolk is planning a massive floodgate — or storm surge barrier — that will extend across the river.

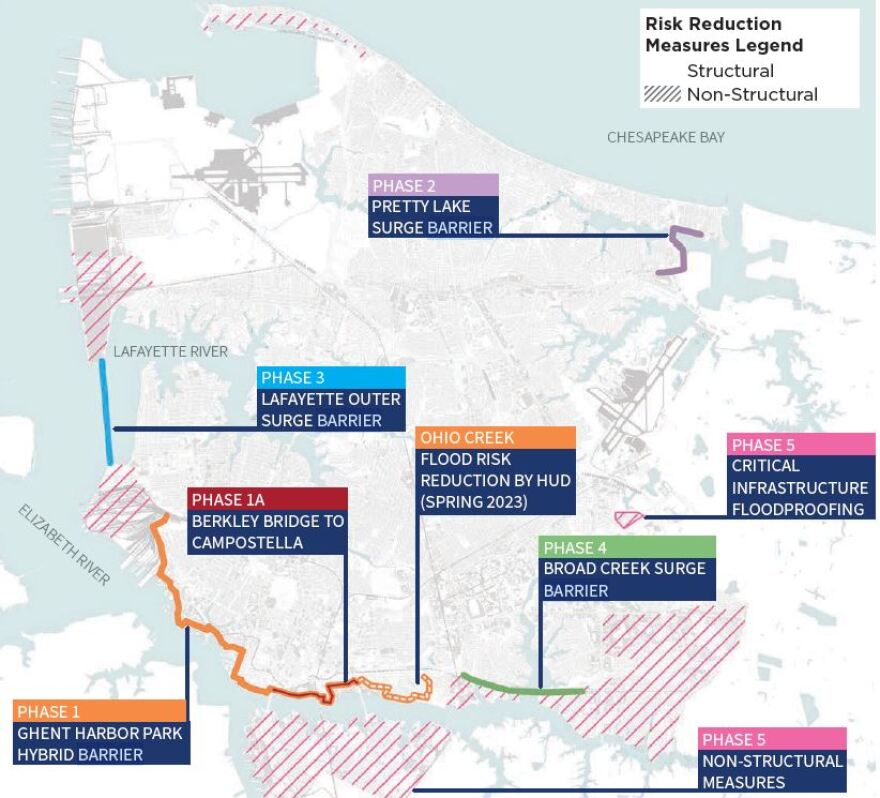

It’s part of the city’s plan to protect itself from catastrophe. Officials have approved floodgates in the Lafayette and three other local waterways to help seal off the city during major storms.

The barriers will be one element of Norfolk’s $2.6 billion storm protection project in partnership with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

The plan, called Resilient Norfolk, is one of the biggest infrastructure efforts in city history.

It will also include levees and a floodwall running from the Campostella Bridge to Lambert’s Point.

The project is designed to protect the city from deadly flooding during a hurricane-type event. (It is not intended to address everyday flooding caused by rain and high tides.)

But environmental advocates worry the planned flood barriers could also cause lasting damage to local ecosystems.

Floodgates that close to keep out excess water might simultaneously trap in pollution, they said. Barriers can also disrupt wildlife migration patterns and contribute to shoreline erosion. That could undermine long-running efforts to clean up local waterways, which have cost state and local governments millions of dollars over decades.

“We have invested a lot of money in restoring these waters,” said Jay Ford, Virginia policy advisor with the nonprofit Chesapeake Bay Foundation. “If we are putting structures in place that are setting them back, we're really spending money in one hand that’s undercutting and increasing the bill in the other hand.”

Kyle Spencer, the city’s resilience officer overseeing the project, said officials plan to address any environmental impacts. He emphasized that the federal project is a “once in a lifetime opportunity” to protect the city before disaster strikes.

Coastal cities across the country are weighing these concerns, especially as climate change is predicted to drive more frequent and intense storms.

The Army Corps has proposed a similar, massive project for the Hudson River in New York, for example. A few surge barriers already exist in New Orleans. But Norfolk will be the first city on the East Coast to move forward with such a project in a generation, after City Council voted earlier this year to approve the Army Corps agreement.

What is a floodgate?

Norfolk and the Corps have not yet designed the planned floodgates. But existing barriers in the Netherlands and elsewhere often look somewhat like bridges stretched across the mouth of a body of water — and made of some combination of steel and concrete. Others look more like an earthen or rocky berm.

The barrier is punctuated by a series of movable gates, which remain open most of the time but can close in anticipation of a major storm.

“You can kind of imagine that these structures would be anywhere from 12 to to 13 feet from the surface of the water,” said Joe Rieger, deputy director of restoration with the nonprofit Elizabeth River Project. “Anyone on land or recreating on the water, it would be a significant change in the feel than what's out there now.”

Floodgates are designed to protect against giant waves generated during major storms. When the gates are closed, they prevent that storm surge from flooding into tributaries like the Lafayette River and overwhelming neighborhoods.

The Army Corps said the barriers can be an economical option at the entrance to large bays and reduce the need for other risk management measures behind the barriers.

The full Resilient Norfolk project is one of many coastal protection projects proposed by the Corps up and down the U.S. coastline after Hurricane Sandy caused billions of dollars in damage in 2012. Congress directed the agency to study how it could protect coastal communities from the next Sandy.

Norfolk’s project is currently the furthest along. The city plans to break ground on the first section of the downtown floodwall late next year.

The floodgates will come next, with construction scheduled to begin around 2026. Spencer said the city plans to host public meetings in the spring to help inform the design.

Officials plan to build the barriers at entry points to waterways including Little Creek at the bridge on Shore Drive; and Broad Creek at Interstate 264.

A barrier at the Hague will be the smallest, while the Lafayette’s mile-long barrier will be the largest.

The only other comparable barrier on the East Coast was constructed during the 1960s in Massachusetts’ New Bedford Harbor.

“We do feel a little pressure because we are kind of first out of the gate with this type of program,” Spencer said. “But it’s a space we're comfortable in. And we've been leaders in resilience for a number of years now.”

Pollution concerns

Environmental advocates worry the floodgates could set back efforts to clean up local water bodies long polluted from historical local industries and urban living.

Virginia public agencies have spent decades working to restore ecosystems around the greater Chesapeake Bay region to preserve the health of the water and wildlife that relies on it.

When it rains in Norfolk, the remnants of city life get swept into local waterways. Cigarette butts, fertilizers, oil, dog poop: downpours wash it all off sidewalks, roads and yards into storm drains that ultimately empty into nearby streams and rivers.

It’s called stormwater runoff, and it’s one of the major sources of pollution in the region’s water bodies. Local environmental groups worry the new floodgates could compound the issue by trapping pollution and preventing it from washing out to sea.

“We've got essentially a bathtub that is now receiving all of the pollutants that are coming off” the city, said Ford, with the Bay Foundation.

Those pollutants can affect marine life and cause harmful algae blooms.

The city and Corps did some analysis of the project’s potential effects on water quality before approving the project – but critics say it was fundamentally flawed, by leaving out rain and stormwater runoff.

Dave Schulte, a marine biologist with the Army Corps’ Norfolk District, said initial modeling of the Lafayette River site did not find significant impacts as a result of building the project or closing the gates. He said the Corps had not yet done modeling at the other sites.

Skip Stiles, senior advisor with the nonprofit Wetlands Watch, said he’s frustrated officials moved forward without more detailed data.

“I feel like we’re remodeling our kitchen, and we bought the granite countertop without knowing what the whole project’s going to be like,” Stiles said.

Environmental groups are particularly concerned that the studies did not account for rainfall, which is expected to increase with climate change.

“These increased rainfalls (are) carrying pollutants from all over the city into these tributaries at the same time as we're modeling closures,” Ford said. “The initial analysis that says we don't think this is going to be a big deal is really predicated on an inaccurate and incomplete picture.”

The City and Army Corps have agreed to conduct a new study of the potential effects of the project on water quality. Stiles and other advocates are pushing for it to be as expansive as possible.

The Corps’ Norfolk District said in a statement that it “shares the concerns about the potential for adverse ecological impacts of surge barriers (especially from operations/closures), including to water quality.”

"With this in mind, outlining a long-term strategic environmental compliance plan is absolutely critical to delivering a successful and acceptable project to the people of Norfolk,” the statement said.

The Corps team is now evaluating whether to study factors like stormwater runoff caused by heavy rains, and markers of pollution in the water, such as algae and nutrients found in fertilizers.

Scarce information on future impacts

Nationwide, there’s little long-term research about the link between storm surge barriers and water quality.

The structures can effectively protect harbors, and minimize flooding and property damage during large storms, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which recently studied the potential environmental effects of a surge barrierproposed in the Hudson River.

“However, even when gates are open, the barriers reduce water flow and tidal exchange, which in turn affects water quality and ecological processes,” NOAA wrote.

Scientists and engineers are “increasingly recognizing the need” for more research to fully explore the advantages and disadvantages, the agency said.

There’s “a big data gap,” said Loretta Fernandez, an associate professor of environmental sciences and engineering with Northeastern University in Boston, who has studied the ecological effects of tide gates.

“With climate change, we’re going to see a lot more tide gates introduced,” Fernandez said. “And we should know how they affect these things.”

Climate change is also driving more intense storms, which could force the city to close the floodgates more frequently once they’re built.

“You're going to have to close those gates more and more and more often to get the same level of protection,” Stiles said.

Eventually, some critics worry, the city could also face pressure to close the gates on a more regular basis, to protect against high tides driven by sea level rise. (Research out of New Jersey shows that’s already starting to happen in the Northeast.)

Spencer, Norfolk’s resilience officer, said the city has not thought about that possibility. He said the city plans to adapt to sea level rise in other ways.

Norfolk plans to address any pollution impacts from the new barriers with mitigation projects around the waterways, a certain amount of which the project cost already covers, Spencer said.

Officials don’t yet know exactly what mitigation measures would make sense, but past efforts have included planting vegetation along the shoreline to absorb some stormwater runoff, or putting in oyster reefs to help filter water.

Spencer noted the barriers will also help prevent storm waves from running onto land and collecting stormwater runoff.

Ford, with the Bay foundation, said such mitigation measures can be helpful. But he would have liked to see the project include more extensive “green infrastructure” from the start. Projects like wetland restoration, for instance, can help absorb and filter stormwater.

“We didn't have to be in a situation where mitigation was the only solution,” Ford said.

Ford and other critics agree Norfolk needs to be protected from catastrophic storms. But they say the barriers should be designed to protect both the built and natural environments.

Rieger, with the Elizabeth River Project, said local groups want to ensure the health of the waterways long-term. Healthy wetlands, rivers and streams are essential for both the local economy and quality of life, he said.

“More and more people are using the river to recreate because they see the improvements that are happening. The water quality is getting better,” Rieger said. “What we don't want to have happen is put these structures in place and the water quality goes down and then people don't want to come and recreate on our rivers.”