Dustin Wright can’t help but find gaps in mental health services.

After getting a master's degree in counseling psychology at James Madison University and spending a decade working in mental health roles around the Shenandoah Valley, Wright opened a counseling practice in Staunton.

But as he worked with families, Wright found the books meant to help them address behavioral problems in children were lacking.

Specifically, he found three main problems.

First, most of the workbooks for kids were exactly that: work. And no one wants to do that after a long day. Second, the books for parents and guardians were written by different authors than the books for kids, meaning their approaches often didn’t line up. And third, he watched parents and kids working from different books increase the divide between families.

“If there's conflict, then that already causes a divide. And we're using our resources [to] continue that divide? That made no sense to me,” said Wright.

So, he wrote his own books that combined education for parents with play therapy for children.

“You got engaging for the kid [and] helpful, educational training for the adult. And then the fact that they're doing it together, it can be healing in and of itself,” he said.

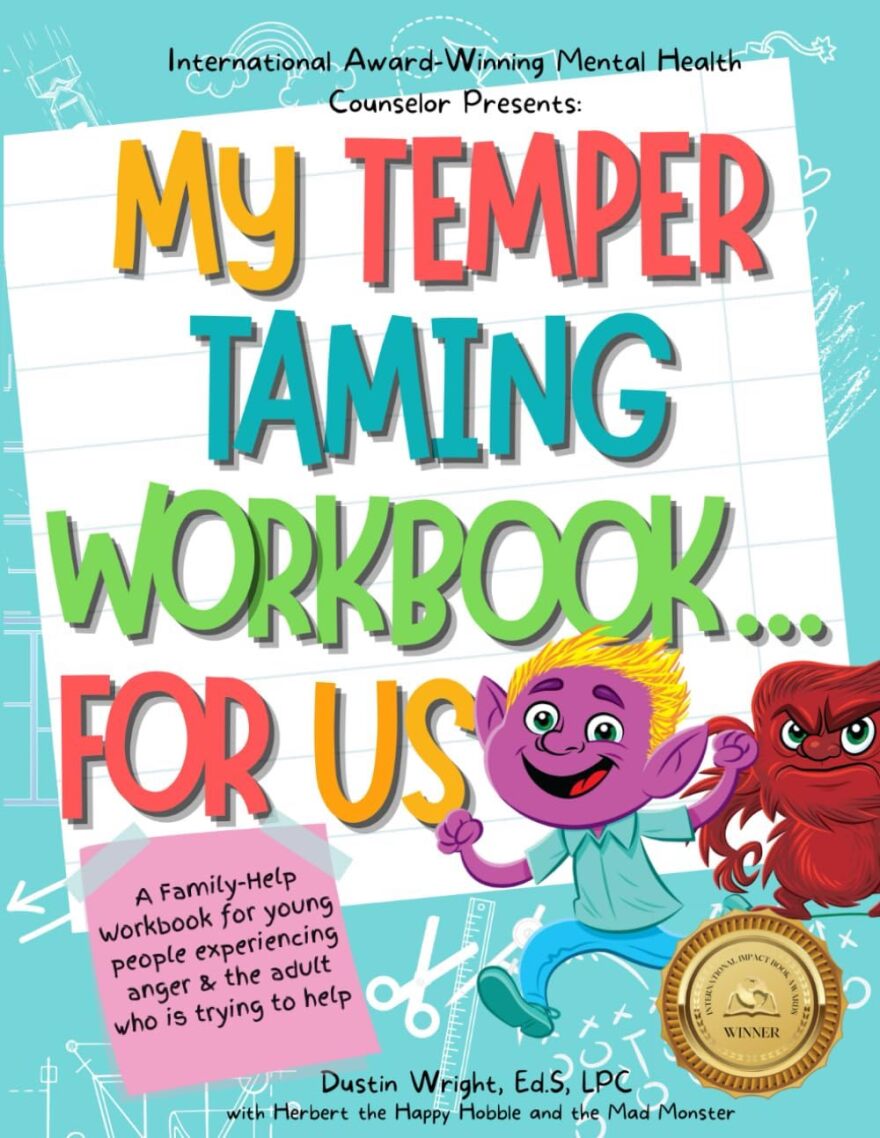

The book that started it all for Wright is called My Temper Taming Workbook... for Us. It’s an anger management book for children and their families.

To make the books engaging, he researched do-it-yourself science projects and found tie-ins to concepts like emotional awareness and self-expression.

“I want you to use the book to get out of the book,” he said. “That is, ‘I read the directions and then I set the book to the side, and me and mom or dad or my adoptive parent — or whoever, my counselor — then we go to the counter and we make this explosion to learn about impulse control.’”

From there, he integrated early versions of the book into his practice and eventually arrived at the book he has today.

“I’d been using that, or some rendition of [that] book, in my practice for five or six years, with my own clients and their families,” he said. “And I started seeing some really good results and positive feedback from the families and encouragement. They would come in and ask me, ‘Can you print out a copy?’”

The book follows main character Herbert the Happy Hobble as he learns to manage his anger.

Wright also has two other books out, one rhyming book to help kids navigate emotions and one early childhood handwriting book that uses handwriting exercises to teach children emotional wellness concepts.

While he wrote the books to address gaps he saw in children’s mental health resources, they ended up coming at a crucial time. Wrightaid’s seen an increase in counseling referrals for kids and said a lot of that is because kids have been struggling with school in the wake of the pandemic.

“Whenever anybody gets behind, they feel overwhelmed. And that overwhelmed sensation can lead to anxiety,” he said. “So I'm definitely seeing an increase in youth referrals for anxiety. And for a lot of young people that does manifest in behavioral kinds of symptoms.”

Nationally, more than one-quarter of high school students reported worsening emotional health and over one-fifth of parents with children ages 5 through 12 reported similar worsening conditions for their children, according to a 2021 report from research foundation KFF.

And rural communities like those throughout the Valley face these challenges to even greater degrees.

More than 60% of rural Americans live in mental health professional shortage areas, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. And over 90% of all psychologists and psychiatrists, and over 80% of social workers practice exclusively in metropolitan areas.

The Shenandoah Valley is no exception. Substantial parts have been designated “Health Provider Shortage Areas” for mental health care for low-income people, according to the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services.

While Wright mostly works with people from the city of Staunton, he knows from his time working for the Valley Community Services Board that these issues are closely related to some of the main struggles of rural life and can impact families hard.

“Less work opportunities, leading to financial stressors, leading to less access to goods, less access to services; more stressors increase our risk for developing mental health conditions like anxiety, depression,” he said.

And he sees that situation often compounds.

“Which then increases our risk for self-medicating with substances that we shouldn't be, which increase[s] our risk for addiction, and it's this big snowball,” Wright said. This is followed by “family members seeking services for the individual. And they look in their community, and they say, ‘What's here?’ And their response is ‘Nothing’ or, ‘Not much.’ And so that is a compounding spiderweb of issues.”

While that situation is dire, it would be unlike Wright to be hopeless about it. He added that mental health providers and public health agencies are aware and working to address this even if funding shortfalls can hurt efforts. He did note his field also has to do a better job promoting the services that do exist.

“I think mental health as a whole needs to do better marketing,” he said. “And we also need to go for more grants and find more people motivated to provide services and meet those holes.”

For Wright, after 10 years working on these challenges, his primary focus is now on continuing to build both his practice and his books — and balancing those with his family.

“I'm a full-time dad, I'm a full-time husband. I'm a full-time clinician running my practice,” he said. “Sometimes, I'm like, ‘You should just stop and like, breathe.’ But I just can't help myself. I see a hole and I'm like, ‘Well, I have the ability to do this, so why shouldn't I?’ And if that means taking some Saturdays and coming here and writing the ABC workbook, then whatever.”