Read the original story on WHRO's website.

Climate change will likely bring more intense storms and higher temperatures year-round to Virginia and across the Southeast. But the region also has the potential to adapt, and some of that adaptation is already underway.

That's according to a sweeping new report from the federal government released this week.

The National Climate Assessment is the government’s most comprehensive report on how climate change is affecting the U.S., and offers people across the country a window into what we can expect in the years to come.

It’s a massive effort, five years in the making, written and reviewed by federal agencies, academics and scientists. The report looks at how the climate impacts everything from health and housing to agriculture, transportation, air quality and local ecosystems.

The U.S. Global Change Research Program released the first such assessment in 2000. This week’s report is the fifth — and most dire.

It confirms that climate change, driven primarily by the burning of fossil fuels, is already impacting the lives of Americans, and that the country needs to adapt to those impacts even while acting to slash greenhouse gas emissions to prevent the worst-case scenarios.

The report finds especially strong impacts in the Southeast region, which includes Virginia.

“The Southeast tends to stick out as particularly, disproportionately affected by climate change impacts,” said Jeremy Hoffman, a climate scientist and lead author of the chapter focused on the Southeast. Hoffman is the former director of the Science Museum of Virginia. He now works as director of climate justice and impact for the nonprofit Groundwork USA.

Residents of the Southeast face some of the greatest risks from stronger hurricanes, for example. The region’s legacy of slavery, segregation and housing discrimination have also led to some of the country’s widest health and economic disparities.

But Hoffman said the region also has huge opportunities to invest in new industries to cut carbon pollution, and to prepare for coming changes, he said. That can “secure the vitality of our communities now and into the future as climate change impacts continue to intensify.”

Here are some of the report’s key takeaways.

Hampton Roads can expect more water and heat

The report reiterates warnings scientists have made for years: Hampton Roads can expect a wetter and hotter future, as temperatures and sea levels rise, and intense rain becomes more common.

- Rising seas: Global sea levels are projected to keep rising, which affects coastlines everywhere. Under the federal estimates that Virginia uses to plan for sea level rise, officials expect up to 5 feet of sea level rise by 2100. But Hampton Roads will experience those effects even faster, because the land is naturally sinking in response to glaciers that once covered it. (In a graphic about disruptive and destructive flooding, at least two of three images depict flooding in Norfolk.) The low end of previous projections have now been eliminated, because they’re “no longer feasible,” said climate analyst Jenny Brennan with the Southern Environmental Law Center.

- More rain and flooding: Climate change is set to increase the amount and intensity of rainfall, because a warmer atmosphere can hold more moisture. Increases in the Southeast will happen mostly during the fall and winter seasons. Hurricanes will be more likely to stall near the Atlantic coast due to warmer water, which would allow them to dump heavy rains on an area for longer periods of time. Sewage and stormwater infrastructure built to accommodate outdated rainfall projections will be overwhelmed more often, contributing to more pollution and flooding.

- Extreme heat and warmer winters: Rising global temperatures will continue to make summers hotter and more humid across the Southeast. That will drive up demand for air conditioning — and energy to power that air conditioning — and make it increasingly perilous to work outdoors on many days of the year, the report warned. Winters will also be warmer: Winter is the fastest warming season in the Southeast, Hoffman said.

Warming temperatures will change how we interact with the outdoors

Climate impacts go far beyond infrastructure. Warming temperatures will affect our jobs and health, what we eat, how we work and even how we commemorate history.

- Threats to agriculture: Climate change will have a major impact on farming across the Southeast. Excess heat puts stress on livestock and affects agricultural workers who labor outdoors. Higher temperatures, particularly overnight, have already reduced crop yields and that’s expected to worsen.

- Warmer waters: Ocean and Bay temperatures are rising, the report said, with major impacts on local ecosystems and recreational activities. Warmer water temperatures can increase the prevalence of invasive species and drive more harmful algae blooms, which make swimming and fishing dangerous and cut off marine life below the surface from needed sunlight and oxygen.

- Impacts on Indigenous communities: Sea level rise of about 3 feet by 2100 — the government’s more conservative estimate — could result in the loss of at least 13,000 historic and prehistoric archaeological sites in the Southeast, while directly harming contemporary Indigenous communities in Virginia. Tribes that were forced off their land generations ago and forced onto less desirable land now face displacement again, this time from climate change. Losing native species also impacts Indigenous people who rely on local species culturally and to eat.

- Disproportionate health effects: Communities of color and those with lower incomes in the Southeast already have higher rates of chronic diseases like asthma and a harder time accessing health care. The report said climate change is making that worse. Families living below the poverty line have a harder time repairing flood damage, and may end up living with toxic mold. Climate change is increasing the amount of pollen in the air, which can worsen asthma and allergies. People who can’t afford air conditioning are most at risk from extreme heat. But the report’s authors said they’re confident that climate mitigation and adaptation efforts can reduce these public health burdens and save lives.

How we build will determine how communities are affected

The Southeast population is growing, and decisions on where and how we build are a big driver of future risk. But communities can plan ahead to lessen climate risks.

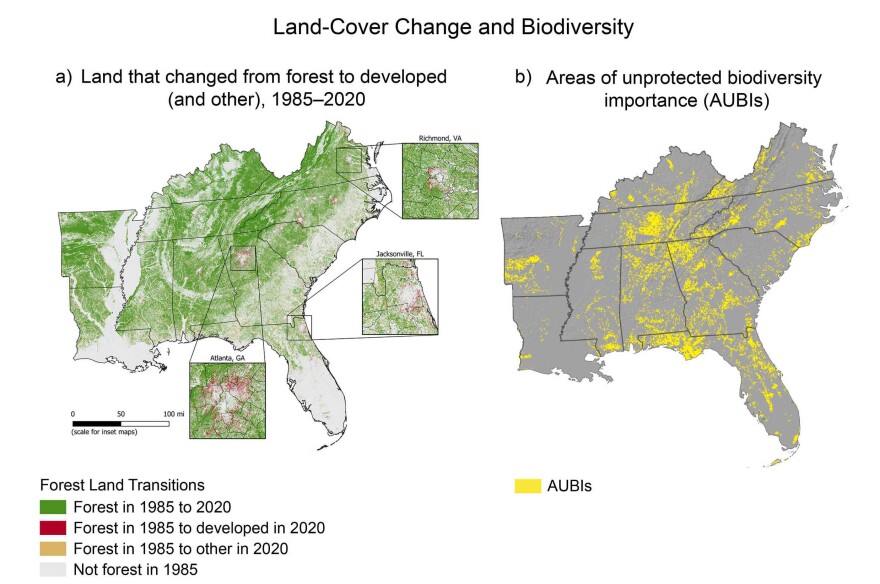

- Development decisions can increase risk: The Southeast population is growing, mostly in urban areas and along the coastline. That means more people are moving into harm’s way. About 1.7 million football fields-worth of land in the Southeast changed from forested to developed between 1985 and 2019 — more than any other region in the U.S. Paved surfaces mean less carbon is stored in the ground and there are fewer places to absorb rain and floodwaters. Paved surfaces also make neighborhoods hotter.

- Or decrease risk: The assessment also outlined strategies coastal cities are starting to use to adapt to the changing climate and lessen these impacts. Those include strategically planting trees and living shorelines to absorb floodwaters and cool neighborhoods, building “green roofs” on buildings and increasing pedestrian and bike access to reduce pollution and greenhouse gas emissions from vehicles. The authors note that more cities could also consider a different type of strategy — buying out homes in especially risky areas to move people out of harm’s way. Currently, buyout programs rarely come with proactive policies to preserve the land left behind.

- Virginia is a regional leader on adaptation: Out of the 11 states in the Southeast region, Virginia has taken the most action to lessen the impacts of climate change, according to the new assessment. The report cites Norfolk’s Ohio Creek Watershed Project as a large-scale resilience project “on the road to adaptation.”

Norfolk used a $112 million federal grant to transform Chesterfield Heights and Grandy Village to withstand flooding. Hoffman also pointed to the commonwealth’s participation in the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, known as RGGI, a multistate carbon market that seeks to cut planet-warming climate pollution. Virginia has set aside money generated from the program for flood adaptation and energy efficiency programs. (Virginia is now set to withdraw from RGGI at the end of the year, under the leadership of Republican Gov. Glenn Youngkin.)

The climate assessment comes at a critical time, said Alys Campaigne, climate initiative leader for the Southern Environmental Law Center. It can be a key resource for local, state and federal leaders as they handle billions of dollars coming from the federal government for clean energy and other initiatives, she said.

“This report provides information that we can use to really level-set and make sure that those resources are used responsibly,” Campaigne said.