Read the original story on DCist's website.

Northern Virginia has cemented its status as one of the most prosperous areas of the state in recent years, with residents enjoying increasingly high incomes, high education rates, good job opportunities, and good access to food, housing, transportation and health care.

That’s in the aggregate. But if you look more closely at individual neighborhoods, a different picture emerges: one of concentrated areas of poverty and poor opportunity alongside others of tremendous wealth and success. That reality persisted — and in some cases, even worsened — as Northern Virginia overall experienced continued growth and progress in the years between 2013 and 2021, according to a new report from researchers at Virginia Commonwealth University’s Center for Society and Health and the Northern Virginia Health Foundation.

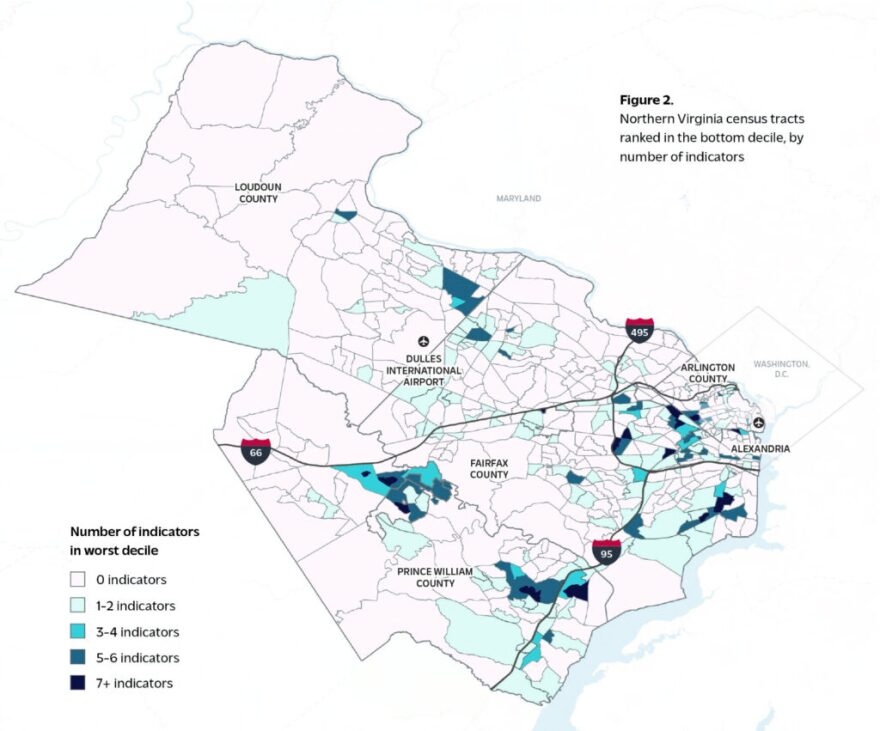

The report, “Lost Opportunities: The Persistence of Disadvantaged Neighborhoods in Northern Virginia,” compares 2017-21 census data for Arlington, Fairfax, Loudoun and Prince William counties and the city of Alexandria to the same data from 2009-13 to understand how the region — and its “islands of disadvantage” have changed over time.

The research builds on a yearslong endeavor to document these neighborhoods and explain why they are struggling amid Northern Virginia’s overall prosperity. An original report used the 2009-13 census data to identify the region’s “islands of disadvantage.” Subsequent reports showed how the region’s history of racial discrimination influenced struggling neighborhoods today, and how residents in those neighborhoods experienced significantly higher rates of premature death than the region as a whole.

Progress at the price of displacement

Between the 2009-13 and the 2017-21 periods, 92% of Northern Virginia census tracts saw gains in household income, 73% had increases in residents with bachelor’s degrees, and 78% of neighborhoods had their percentage of people without health insurance go down. About half of the neighborhoods saw decreases in poverty rates.

Most neighborhoods also became more racially diverse, with a majority of census tracts seeing increases in their Black, Hispanic and Asian populations. (Just 27% had increases in their white populations.)

Some “islands of disadvantage” were lifted by that overall progress. The report notes that one census tract in Arlington’s Columbia Pike neighborhood had its poverty rate drop by 34% between the two periods, along with decreases in the uninsured rate, the unemployment rate and reliance on public assistance.

The report acknowledges the work of local governments and nonprofits to promote equity and target investments in marginalized communities. Several Northern Virginia localities, for instance, now require consideration of the racial and socioeconomic impacts of policies before they are implemented. Some of the progress in struggling neighborhoods may be related to those efforts, the report suggests.

Another factor in the improvements seen in the 2017-21 data may be the COVID-19 relief programs put in place to prevent evictions, support people suddenly thrown out of work, and provide consistent health care to vulnerable residents.

“Future analyses of data from 2022 and beyond may reveal the degree to which that progress was short-lived (as COVID relief expired) or was long-lasting,” the report notes.

But for some neighborhoods whose fortunes did improve, there was another important driver.

“The data indicate that progress in some areas may have come at the price of displacement,’” said Steven Woolf, the report’s lead author and director emeritus of VCU’s Center on Society and Health, in a press release. “Some neighborhoods that historically were home to people of color became upscale, gentrified, expensive—and increasingly White.”

In Arlington’s Courthouse neighborhood, for example, the median household income jumped from $87,233 to $132,603 between the two five-year periods, and the poverty rate dropped from 19% to 5%. In the same period, however, the neighborhood became majority-white: In 2009-2013, whites accounted for 48% of the population, and they now account for 68%. Meanwhile, the Black population in the community declined by 42% and the Asian population declined by 72% over the same period.

Other neighborhoods in the closer-in suburbs are experiencing similar displacement trends, including Old Town Alexandria, Annandale — and Green Valley/Nauck, a historically-Black neighborhood in North Arlington.

In some struggling neighborhoods, things got worse

But plenty of neighborhoods did not share in regional progress on poverty, employment, education and other measures. Despite the efforts of local governments and the boost from COVID-19 relief programs, every jurisdiction in Northern Virginia has multiple neighborhoods where poverty and other indicators got worse between the two five-year periods.

One census tract in Bailey’s Crossroads in Fairfax County saw the poverty rate nearly double, from 17% to 30%, and child poverty jump from 32% to 63%. Unemployment skyrocketed from 2% to 11%, and the number of people living in overcrowded housing increased from 6% to 16%.

There are similar examples of declining social conditions all over Northern Virginia. Overcrowded housing increased by 122% in Sterling, in Loudoun County. One census tract in Alexandria saw the part of the population with a Bachelor’s degree plummet by 24%. In Hybla Valley, in southern Fairfax, one census tract saw the uninsured rate increase by 123%.

Worsening poverty and other setbacks in education, employment, and overcrowded housing often came alongside increases in the percentage of residents of color and decreases in the percentage of white residents, meaning that deteriorating conditions tended to disproportionately affect Northern Virginians of color. As conditions worsened in Bailey’s Crossroads, for instance, the share of the white population decreased from almost half to just over one-third. In some parts of Manassas, poverty, overcrowding, and lower educational levels corresponded to an increase in Hispanic residents living there.

Northern Virginia Health Foundation President Patricia Mathews believes the findings, sobering as they are, could help local governments and nonprofits figure out how to better target social programs and investment in the region.

“Everyone deserves to share in our region’s social and economic progress—not just those who are already doing well,” she said in a press release. “For that to happen, we must dismantle the structural barriers that stand in the way.”

The report offers a list of general policy ideas that might help in that mission, including expanding access to preschool, increasing access to healthy food, putting in place more public transportation, and building more affordable housing in neighborhoods that are thriving. It also emphasizes the need for governments to continue their efforts to directly address systemic racism and racial discrimination towards communities of color.