Devon Chester runs Brook’s Stitch and Fold, a full-service laundry company in Highland Springs. Chester, whose background is in architectural engineering, said he purchased a former Fan District laundromat in 2015 because he wanted control of his life.

“I relocated to Virginia initially back in ‘08. I was working on a project here at the [Defense Logistics Agency] and really decided to dig in roots,” Chester said. “I wanted to get off the road and just kind of do my own thing again.”

When Chester bought the laundromat, he transitioned to full-service laundry, or “wash, dry, fold,” which was common in his home state of Michigan. He said while owning a business may give him control, it doesn’t give him ownership of his time.

“You find yourself wearing multiple hats. You have to be able to dig into the weeds, as well as think big picture and how you’re going to grow the company,” Chester said. “And you is best to make sure that you love what you’re doing, because 24-hour workday is pretty much what you’re doing.”

Chester said one thing he likes best about owning his own business is his ability to give back. He said the business has partnered with local organizations including Caritas and Home Again.

“Any business should be a pillar of their community and should always be looking at seeking ways to give back and not just extract or take for the community that they serve,” Chester said. “I think that being in a position to do so is a responsibility that I shouldn’t run from, but one that I should embrace.”

Willow Lung-Amam, an urban planning professor at the University of Maryland, said small businesses across the country hold that value. She said locally-owned businesses provide greater economic benefits to the communities they service than chain stores.

“Local workers are much more likely to be employed by these businesses. … Local businesses help to circulate dollars much more readily in communities,” Lung-Amam said. “We also get other kinds of external business benefits, like the likelihood of these businesses contributing to local organizations and schools and charities and other kinds of things that help us sustain those neighborhoods.”

Lung-Amam also said local businesses also help to build neighborhoods’ character. She said they act as landmarks for their community and serve the special interests nearby residents.

“Not every neighborhood is the same. Not every neighborhood uses the same kinds of services. They don’t eat the same kinds of foods. They don’t use the same kind of entertainment and cultural venues,” Lung-Amam said. “Small businesses really help to service those unique needs that neighborhoods have.”

Breaking down the numbers

In Richmond, the benefits provided by locally-owned businesses aren’t spread evenly.

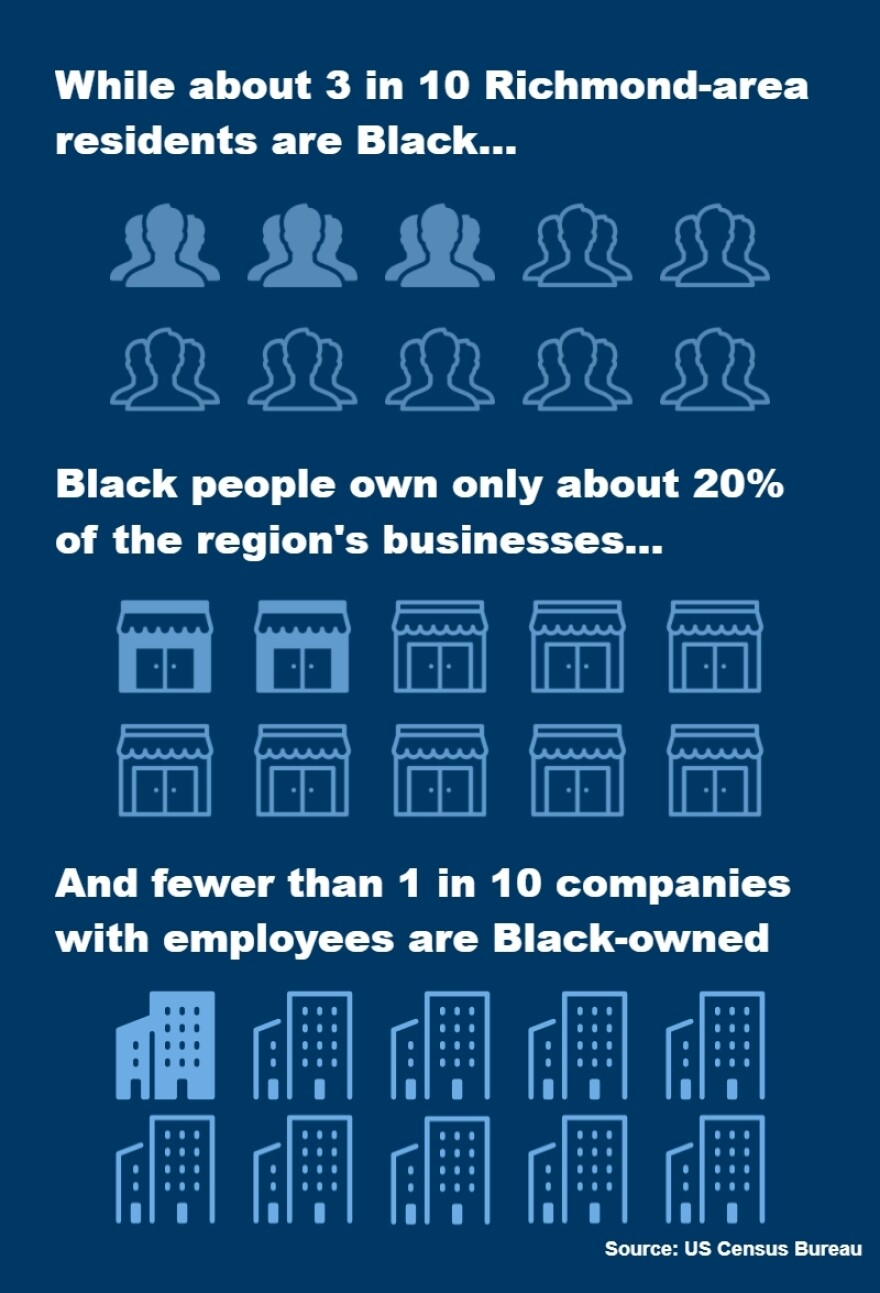

Nearly 30% of people living in the Richmond area are Black, according to Census Bureau data. Yet, Black people own only about 20% of businesses in the area.

And the businesses owned by Black Richmonders tend to be smaller. Among Richmond-area companies that employ at least one person, only about 7% are Black-owned.

That reflects structural barriers placed in the way of Black people. One major barrier for many Black entrepreneurs: access to financing.

Nationally, areas where a majority of residents are Black receive significantly less small-business funding than areas where a majority of residents are white. According to Portland Business Journal in Oregon, “Majority-Black census tracts with more than 500 people averaged $157 in small-business loans per person in 2018. Majority-white census tracts averaged $302.”

A Brookings Institute study of the Atlanta metropolitan area also found that banks charged 1% higher interest rates on business loans in Black neighborhoods.

Chester said he experienced lending difficulties when he first started up Brook’s Stitch and Fold.

“It's sad to say, but they almost want you to be established before they want to lend to you,” Chester said. “And the irony of it is ... you're seeking those funds and assistance because you're trying to get to that point where you don't need it.”

He said he was lucky to eventually secure funding through a private lender, “but going through that traditional means, we found ourselves getting great lip services. But it never felt like it got to the point where you got to put ink to paper, and it seems like the deals always fell apart.”

Melody Short is a co-founder of the Richmond Night Market who's worked for decades to help other Black entrepreneurs get their businesses running. She said many of the founders she’s worked with struggle to get financing from traditional banks.

“I'm thinking about one local business in particular that needed a loan and was denied by multiple financial institutions in the process,” Short said. “The part that's so interesting is what [the bank was] asking for was assets alone. [The business] had assets that far exceeded their ask, but they also have receivables that come in on a recurrent basis that far exceeds the ask. And so one can only think that they were denied because it's a Black-owned business and because of the location of the business.”

"Make sure that you love what you’re doing, because 24-hour workday is pretty much what you’re doing."

A 2021 study of Paycheck Protection Program lending in Washington, D.C., conducted by the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, found evidence of explicit racial bias. In another study from 2018, NCRC sent “mystery shoppers” into banks to track their experiences. Black testers were less likely to be approached by bank personnel, more likely to be asked to provide additional information and less likely to be given information about loan fees than white testers.

There is a circular relationship between small-business lending and the racial wealth gap in the U.S. Black Americans control one-sixth the wealth of white Americans, on average. A similar pattern holds true for business owners. 2016 data showed that businesses started by Black Americans begin with one-third as much capital as those started by white Americans, “making it more difficult for them to survive and generate wealth for their owners,” according to research from JP Morgan Chase.

“Black business owners, historically speaking, do not have access to the resources other groups have,” Short said. “Our goal is to help strengthen the foundation of Black-owned businesses so that there's longevity, and so that they're able to create legacy for their community and for their family.”

Soliél Lindsey said that’s what she wants to build with her business, Sol Rise Essentials. Lindsey runs the online clothing shop out of her Southside home and said she hopes it can create ease for her family.

“Where we're not struggling and always in a fight or flight stance,” Lindsey said. “Just living a life that fits for us and helping people along the way.”

Sol Rise Essentials sells clothing and accessories imprinted with affirmations and other phrases related to mental health. Right now, her site’s got hoodies that say “Do Good. Be Good.” and hats with the phrase “pack light” — inspired by Erykah Badu’s “Bag Lady,” according to Lindsey — among other items.

Lindsey grew up in Richmond’s Highland Park neighborhood and said she experienced several traumatic events while young. Lindsey said she often found herself in trouble in school, but she was able " to do a 180 in my life” by affirming herself and surrounding herself with others who did so.

“I wanted to teach people that you can go from getting expelled from multiple schools ... to getting in good trouble is what I like to call it,” she said. “I get to do that through my business, even though it's clothes and accessories. There's more to it than just that.”

She said she wants her products to remind people of the importance of prioritizing their mental health — something she learned after experiencing her first panic attack at age 17. She didn’t know what was happening at the time and avoided leaving her house for a while afterward, because she worried about having another.

“Now, I've educated myself more on what my brain was doing while I was experiencing those things,” Lindsey said. “Now that I knew what my body was doing, I'm like, ’OK, I can eat better, I can sleep better, I can get educated on mental health, my brain, the trauma that I've experienced.’ My granddad and I can move forward with different lifestyle practices.”

When Lindsey started Sol RIse Essentials in 2021, she didn’t know much about the details of running a business.

“It's a lot to it on the back end, versus just serving and having a product,” she said. “What is cash flow? What is the profit and loss statement? All of this stuff. I was hearing this terminology when I got into the business world, but I'm like, ‘What does any of this even mean?’”

Lindsey attended various online and in-person programs to help grow her business acumen after starting Sol Rise — something she said she was lucky to be able to do: “How did people do business in the 1900s before all these programs and stuff existed? How did you get this information?”

In addition to learning the basics of marketing, bookkeeping and more, the programs challenged Lindsey’s expectations for how successful Sol Rise could be. She said it can be difficult to picture that sucess since she’s never seen anyone in her family achieve what she wants.

“A lot of people just talk about, ‘You can make this amount of money, you can do this, there are these opportunities.’ But if you don't believe deep down that you can do it and that you're worthy of it, then is it ever gonna happen for you?” Lindsey asked. “I'm honestly still pushing past that.”

The other major challenge Lindsey has faced is financing. When Sol Rise launched, she was “bootsrapping,” meaning the company ran without outside financing. Now, Lindsey’s looking for more financial support — but not a loan. Instead, the strategy currently is to apply for grants, and she’s considering crowdfunding through a microlending platform like Kiva.

On the other hand, Lindsey hopes to move the business out of her home soon and into a warehouse space. To raise enough money, she’ll likely have to apply for a loan and take on debt.

“That is not a bad thing if I'm looking at it from a business standpoint. But it's a lot of work and I might just be a little bit afraid. But I'm gonna do it,” she said.

Short said for business owners struggling to get investment from large banks, she recommends looking at Community Development Financial Institutions — which are required to primarily serve moderate- and low-income areas. Short pointed to Locus, a local CDFI formerly known as Virginia Community Capital.

“A lot of Black-owned businesses, they are not even familiar with CDFI. So they wouldn't even know to go to these community banks to see if they could get a loan or a line of credit,” she said.

Short said Locus runs a fund that lends specifically to female entrepreneurs and entrepreneurs of color to help them grow their business and ensure its stability — including by helping them purchase property.

Short said that’s key for building long-term stability in majority-Black neighborhoods. She pointed to the history of Richmond’s Jackson Ward neighborhood — formerly known as “Black Wall Street” — as proof of the power of local financial control.

“Historically speaking, we have a history of paying rent to non-Black property owners. And so what happens is the property owner is the one that becomes a fat cat,” Short said. “We want to shift that narrative so that we are not only business owners, but we're also commercial real estate owners as well.”