Read the original article on WHRO News' website.

Hundreds of thousands of pounds of cargo move through the Port of Virginia each day, handled by massive pieces of equipment like cranes, forklifts and straddle carriers.

All of that infrastructure was usually powered by diesel, a fossil fuel that releases emissions when burned that contribute to climate change by trapping heat in the atmosphere.

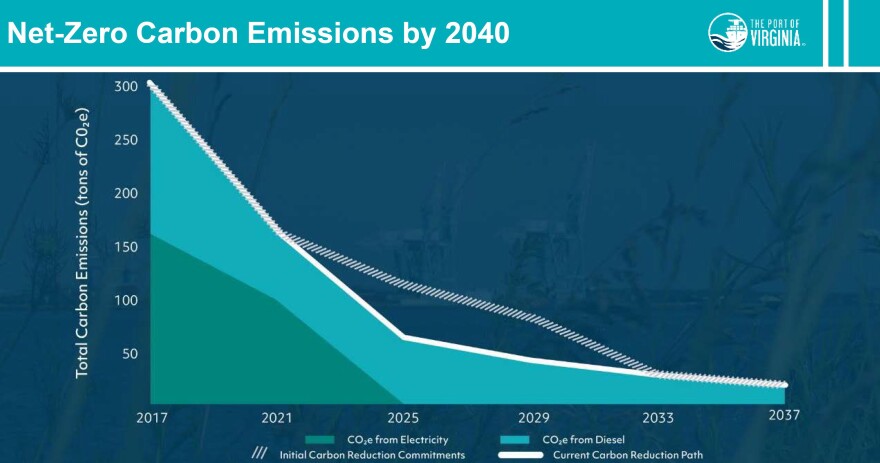

But Virginia’s main port has slowly been working to transition to a clean-powered operation. It’s part of a larger vision to produce net-zero carbon emissions by 2040.

This month, the port achieved its first major milestone: using electricity that comes from only renewable energy sources like solar, wind, nuclear and hydro-power. Officials ensured that through a power purchase agreement with Dominion Energy and a rider with Rappahannock Electric Cooperative.

“This is a modern approach to meeting our environmental targets and we are setting ourselves apart as a result,” Stephen Edwards, CEO of the Virginia Port Authority, said in a news release.

Norfolk’s the first major East Coast port to fully run on clean energy, according to the authority.

The state already contracted with Dominion for solar generation from several farms — including one in Chesapeake — to be dedicated for state agency facilities, said Cathie Vick, chief of development and public affairs at the Port of Virginia.

The port’s included in that, but petitioned to take a higher share to meet its needs.

Now, their focus will shift to slashing greenhouse gas emissions to reach net-zero within the next 16 years. That means replacing machines that use fossil fuels with those that run on electricity and finding ways to cut emissions through better efficiency.

Vick said officials have been doing so piecemeal for awhile. Since 2015, the port’s been switching to hybrid shuttle carriers and now has more than 100. Those use 50% less diesel fuel.

They also started moving more containers to Richmond by barge instead of carbon-intensive truck trips.

Another major investment was a new electric rail-mounted gantry crane system that uses an algorithm to move boxes into place at night. Vick said it’s connected to a truck reservation system that schedules truck pickups to cut down on drivers idling while waiting to collect cargo.

The clean energy transition is an important business move to attract cargo owners to the port, Vick said.

Customers like Amazon, Lego and Walmart have their own emissions targets to hit and had started asking the port about its practices, she said.

At the time, the Port had completed some improvements but had no overall strategic plan on the issue. But a few years ago, they made one, committing to net-zero carbon emissions by 2040.

Vick said that could include using carbon offset programs — which grant entities credits for actions like planting trees that absorb carbon — to supplement when the replacement of equipment falls short or takes too long.

“The technology does not always keep pace with our desire,” she said.

They’ve had challenges with yard tractors, for example, because its significant weight quickly degrades electric charge.

The federal government also recently opened up new opportunities for helping ports go green.

A Clean Ports Program under the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and funded by the Inflation Reduction Act will launch this year. Vick said the Port of Virginia plans to apply, which could help them accelerate buying new equipment.

The port’s also looking into using “green hydrogen” fuel as the local market expands.

The Port of Virginia handled a record-breaking amount of cargo in 2022. Last year’s numbers weren’t quite as high, but remain above pre-pandemic levels.