In the middle of Richmond’s Church Hill neighborhood stands a Greek Revival–style landmark, almost frozen in time. Fourth Baptist Church sits along P Street, surrounded by signs that say “Coming Soon” and other markers of gentrification.

As a part of the Getty Foundation’s Conserving Black Modernism grant program, the Richmond church will receive $150,000 to protect Ethel Bailey Furman’s modernist addition to the building.

The Getty initiative aims to rectify the narrative of modernism in the United States, which historically has omitted Black architects. The funds will go toward conservation planning, professional development and storytelling projects to commemorate and safeguard the historic structure.

Established in 1859 by 23 enslaved Virginians, Fourth Baptist is one of the oldest Black churches in the commonwealth. The congregation began meeting in the basement of Leigh Street Baptist Church and reorganized after emancipation as the Fourth Baptist Church on Dec. 2, 1865.

Church members built their own place of worship using wood from nearby abandoned Confederate military barracks at Chimborazo Hill. That structure was replaced in 1874 by a building that burned down in 1884. The doors of the current site opened a month later.

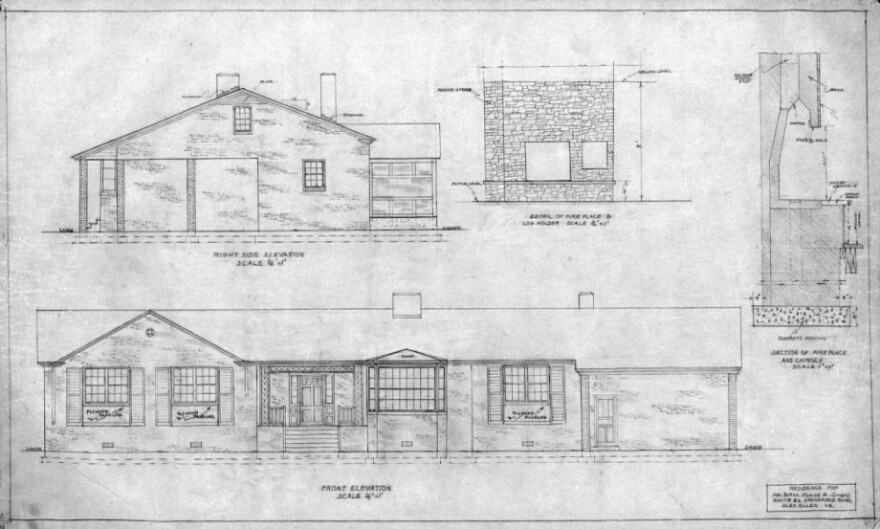

Bailey Furman, the earliest known practicing Black female architect in Virginia, designed an addition to the church in 1962 to create more space for education programming. And through the years, the church continued to add to its campus, incrementally purchasing surrounding parcels of land.

James Wallace, a church member and historian, credited Fourth Baptist trustees in 1992 for some of the later acquisitions.

“We had a trustee by the name of John Taylor Junior, and he came up with the idea and attitude, ‘Well, why not acquire as much land around the church for parking and our use as we could?’” said Wallace.

The church considered using some of its land for senior housing, but due to pastoral transitions, the plans didn’t come to fruition, said Esther Quarles, another church member and historian.

Fourth Baptist later purchased another nearby 2.5-acre parcel and now owns everything on the block — other than a privately owned convenience store. Wallace also said the church owns a few parcels across the street, though he didn’t specify which ones. The church has been approached numerous times to sell its land, he said.

“We lived in this area and grew up in this area. Not only would everyone come here, not only for church service, but for other activities during the week,” Wallace said. “It was the center of the Black community, almost.”

Bailey Furman — the daughter of Madison J. Bailey, Richmond’s second licensed African American contractor — designed an estimated 200 residences and churches throughout Central Virginia, according to Brian Goldstein, an architectural historian and assistant professor at Swarthmore College.

Few of those structures remain today. Among Bailey Furman’s designs that no longer stand is the childhood home of Douglas Wilder, who later became Virginia’s first Black governor, at P Street and North 28th Avenue in Richmond.

Prior to any training in the 1920s, Bailey Furman already had been recruited by her father to work as a draftsperson in his firm. At the time, Black women weren’t permitted to pursue a formal education in Virginia. So, Bailey Furman went to New York for an apprenticeship and then to the Chicago Technical Institute to study architecture.

Throughout her studies and her career, Bailey Furman sometimes submitted her designs using the names of male colleagues to avoid bias. Her work tended to draw on modernism, though Goldstein described a complex relationship between the design aesthetic and minority groups during the 20th century.

“A lot of African Americans, and in general, people who were in a minority status, or were seen as others, in a global sense, were often at the receiving end of modernism in ways that were very harmful,” he said, mentioning concepts like “urban renewal.” “At the same time, I think, there's a group of architects who are being trained at this time, who are Black people, and they, of course, see a lot of the utopianism of modernism. It’s very inspiring, and [they] want to sort of imagine in that way, too.”

Amaza Lee Meredith

At about the same time that Bailey Furman was working, Amaza Lee Meredith was pushing at the boundaries of modernism in Petersburg.

Upon completing her master's degree in 1935, Meredith established the arts department at Virginia State University and served as its chairperson until her 1958 retirement.

During her time at VSU, Meredith designed Azurest South, which served as both a residence and workplace for her and Edna Meade Colson, the architect’s partner.