Read the original article on WHRO's website.

Sixty years ago on April 11, Gen. Douglas MacArthur — one of America’s most revered and controversial military figures — came to his final resting place in Norfolk.

MacArthur, who now stands in the shadows of a mall bearing his name, was born in Little Rock, Arkansas. But he had deep family ties to Norfolk, according to MacArthur Memorial archivist James Zobel.

“His mom was from here — her family lived across the river — the Elizabeth River right on the Southside, where the Berkley Bridge is,” Zobel said. “He would come spend his summers here with his mom and dad, and he could remember it.”

As an adult, MacArthur made history as a five-star Army general and through numerous major accomplishments, like developing island-hopping in the Pacific theater of World War II — which allowed the U.S. to regain control of the Philippines from Japan — and accepting the Japanese army's surrender.

Later, MacArthur was put in charge of the American-led United Nations troops during the Korean War until President Harry Truman removed him from the position.

After that, MacArthur lived the rest of life quietly in New York City until his death in Washington, D.C., in 1964. He was 84.

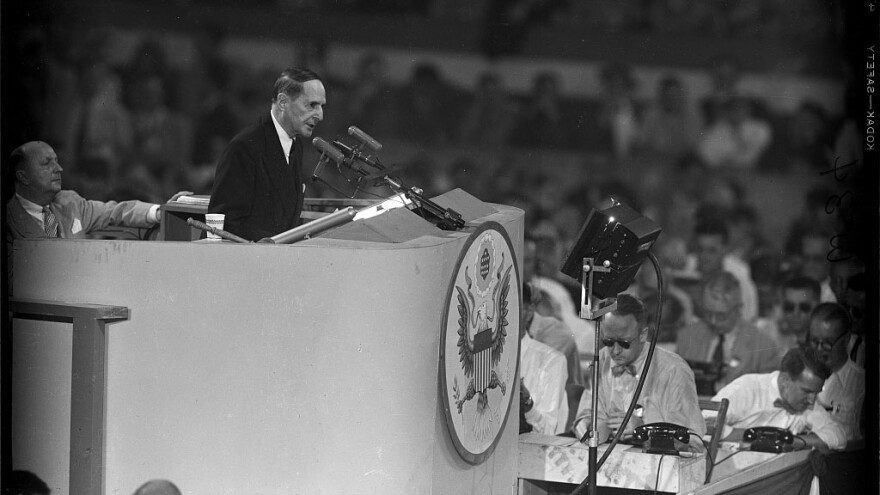

Douglas MacArthur was tapped to run for office as a Republican several times after his military career ended but instead stuck to the sidelines, like speaking at the 1952 Republican National Convention.

The general’s final resting place was Norfolk’s old City Hall. Then-Mayor Fred Duckworth had ordered construction of a new civic center during a massive redevelopment in 1960, and the old structure sat empty.

When the idea to turn it into a memorial came about in 1960, it was seen as an economic boon for the city — but it wasn’t without controversy.

Norfolk’s segregationist policies at the time were at odds with MacArthur’s own beliefs, as related in his thoughts about the U.S. Army's desegregation.

It’s likely he would’ve insisted a his memorial be open to everyone, Zobel said.

“MacArthur said no way, he said, ‘I’m not going to agree to it if this [is] going to be some kind of segregated place where not everybody can go to,’ ” Zobel said. “And it was the only place in Norfolk where Blacks and whites could go to in those early days.”

MacArthur died on April 5, 1964, at Walter Reed Hospital. His body arrived at Norfolk Naval Air Station on April 9.

The procession assembled at 21st Street and Monticello Avenue, where a horse-drawn caisson wagon slowly moved toward downtown. Spectators were 10-deep on the sidewalks.

Bill Zimmerman was a veteran from New York who stayed in Norfolk following his stint in the Navy. He watched the procession from St. Paul’s Boulevard.

“[There were] hordes of people there,” he said. “There was a limousine, but behind the limousine walked the young [Arthur] MacArthur, and followed by many notables either in cars or walking. It was virtually silent, as I remember it. There were no bands, many flags.”

Zobel said it was one of the biggest events ever in the city of Norfolk, with some estimates saying there were 150,000 people present.

“You have all these plans in the works and ready to go because you have so many people and it really does go off without a hitch,” he said. “They bring him down on the 9th and he lays in state there in the memorial from Thursday night to Friday night, and 87,000 [people] go through and it stays open all night long.”

Andrea Yesalusky was 8 years old at the time and said she remembers standing in line with her mother to visit the memorial.

“My parents felt like it was important for me to see this historical moment,” she said. “To me, it seemed like there were a lot of military officials, important people around — somber, quiet, respectful.”

After the procession, the general’s body was moved to St. Paul’s Episcopal Church. The period of national mourning ended at sunset on April 11 when a battery at Fort Monroe fired a final 19-gun salute to hail an adopted son of Hampton Roads.