Tropical Storm Debby closed parts of Interstate 95 in North Carolina on Thursday as it moved toward the commonwealth. And while Gov. Glenn Youngkin declared a statewide emergency earlier this week, Virginia’s farms and forests will likely benefit from the rain.

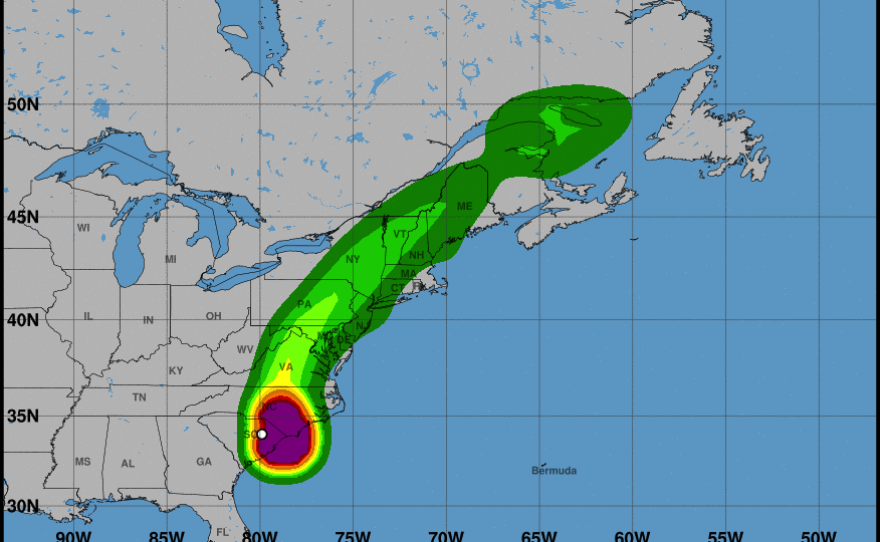

Seven deaths have been attributed to the storm as of Thursday morning, and forecasters have warned of potential hurricanes in both Virginia and North Carolina, according to The Associated Press. The National Weather Service has issued a tornado watch for Williamsburg and said to look out for possible flooding in Richmond, Charlottesville and Harrisonburg.

NWS has also issued flash flood warnings in parts of Southside and Southwest Virginia.

Out of the state’s 95 counties, 23 have USDA Drought Disaster Designations; about 4 million people live in those areas. The federal agency said the designations aren’t uncommon and enable localities to access assistance programs.

Northern Virginia and the Shenandoah Valley are faring the worst. According to an Aug. 8 U.S. Drought Monitor map, both regions are experiencing extreme drought.

John Benner, the Virginia Cooperative Extension unit coordinator for Augusta County, said the past two years have been particularly difficult, comparing the drought to those in 1977 and 2001. He said the coming rainfall is “sorely needed.” But for grains like corn, soybeans and wheat, severe drought has already set a ceiling on yields.

“So, rain at this point doesn't really save much of those crops,” he said.

Corn that doesn’t do well can be used for animal feed — or silage. But Benner said underdeveloped cobs don’t provide much energy for livestock. And drought conditions last year mean many livestock farmers have low stocks of wheat for their animals. The rain could help with another animal food source, though.

“This rain will be instrumental in helping livestock producers have some fall grass,” he said.

That would reduce the need for other food sources in the early fall. Overall, Benner said, livestock producers likely will fare better than those looking to haul in crops this year.

“We've had dry summers before, and we've had dry falls,” Benner said. “But 2023, you had a dry spring, dry summer, dry fall.”

Low yields will impact farms’ income, too. Benner said a farm that averages 140 bushels an acre could lose most of that — possibly producing 30-50 bushels this year. He estimated that to be a $300-$500 decrease in income per acre.

There are some protections for farmers, Benner said, referencing the USDA funds now accessible to 15 localities across the state.

Public land in the commonwealth has been affected by the drought as well. In addition to Virginia’s 22 national parks, the George Washington and Jefferson national forests in the western portion of the state cover more than 1 million acres of land.

Adam Downing, an extension agent based in Madison County who specializes in forestry, said a healthy tree can deal with a few years of drought without a problem. But after that stress, “drought can be the nail in the coffin” — pointing specifically to oak trees.

“The way that [drought] expresses itself in trees is that they become more susceptible to other pathogens, whether it's insects or disease,” Downing said. “Or in the case of urban trees, limited root zones.”

Downing said Virginia’s trees are getting toward the end of their growing season for the year. And while the rain will help nourish them, if soil remains saturated and significant storms send gusts of wind through the commonwealth, some trees could become unstable.

The Virginia Drought Monitoring Task Force tracks drought indicators, including river and stream flow, soil moisture and groundwater.

According to a July 30 DMTF report, some areas of the commonwealth are improving: Rains prior to Debby’s arrival along the Virginia–North Carolina border brought needed moisture to the Southeast.

Water Supply Planner Trevor Lawson told VPM News the task force will evaluate the impacts of Debby’s rainfall on groundwater, soil moisture and stream flows at an Aug. 13 meeting.