A long history led Richmond to its recent water crisis.

One factor: Some of the city’s water infrastructure is more than 100 years old.

Dwayne Roadcap, director of the Virginia Department of Health’s Office of Drinking Water, said that comes with responsibilities.

“What that means is you have to be very good about your operation and maintenance, and checking systems and verifying that they're working, that you're doing the asset management that you need to be doing,” Roadcap said.

A 2022 Environmental Protection Agency audit of the water system found that no asset management plan was in place for Richmond’s drinking water infrastructure. A separate 2024 internal city audit details those missing systems.

While filing the document with VDH isn't required, an asset plan's been requested from the city — but not received. A representative for Richmond’s Department of Public Utilities did not respond to multiple requests for access to the document, if it exists.

The Richmond Times-Dispatch reported the key piece of equipment that failed during the power outage at the plant in early January had been slated for removal for eight years.

The EPA report, completed with assistance from the state’s drinking water office, comes with pages of photos showing a rusted, leaky and malfunctioning water system. Federal inspectors documented extensive rust on valves, pipes and on the outside of water tanks — along with malfunctioning meters and chemical leaks.

One pipe, located at the Warwick Road storage tank, appeared to be propped up by pieces of wood.

Roadcap said the EPA report speaks to the need to update processes and hardware, and that ODW would look into the city’s capital improvement plan, asset management plan and emergency management plan. At the time of the EPA report, those documents had not officially been updated since at least 2017. New plans from 2020 and 2021 were provided to the EPA, but were unsigned.

“Part of it was built in 1924 and another part in 1950,” Roadcap said about the city’s water processing system. “There's ample opportunity to improve upon that infrastructure over time.”

An EPA spokesperson said the results of the audit were discussed with DPU leaders in 2022. A spokesperson for the city department didn't respond to questions about when the city became aware of the report and what accounted for a delayed response to its findings.

Nineteenth-century plans

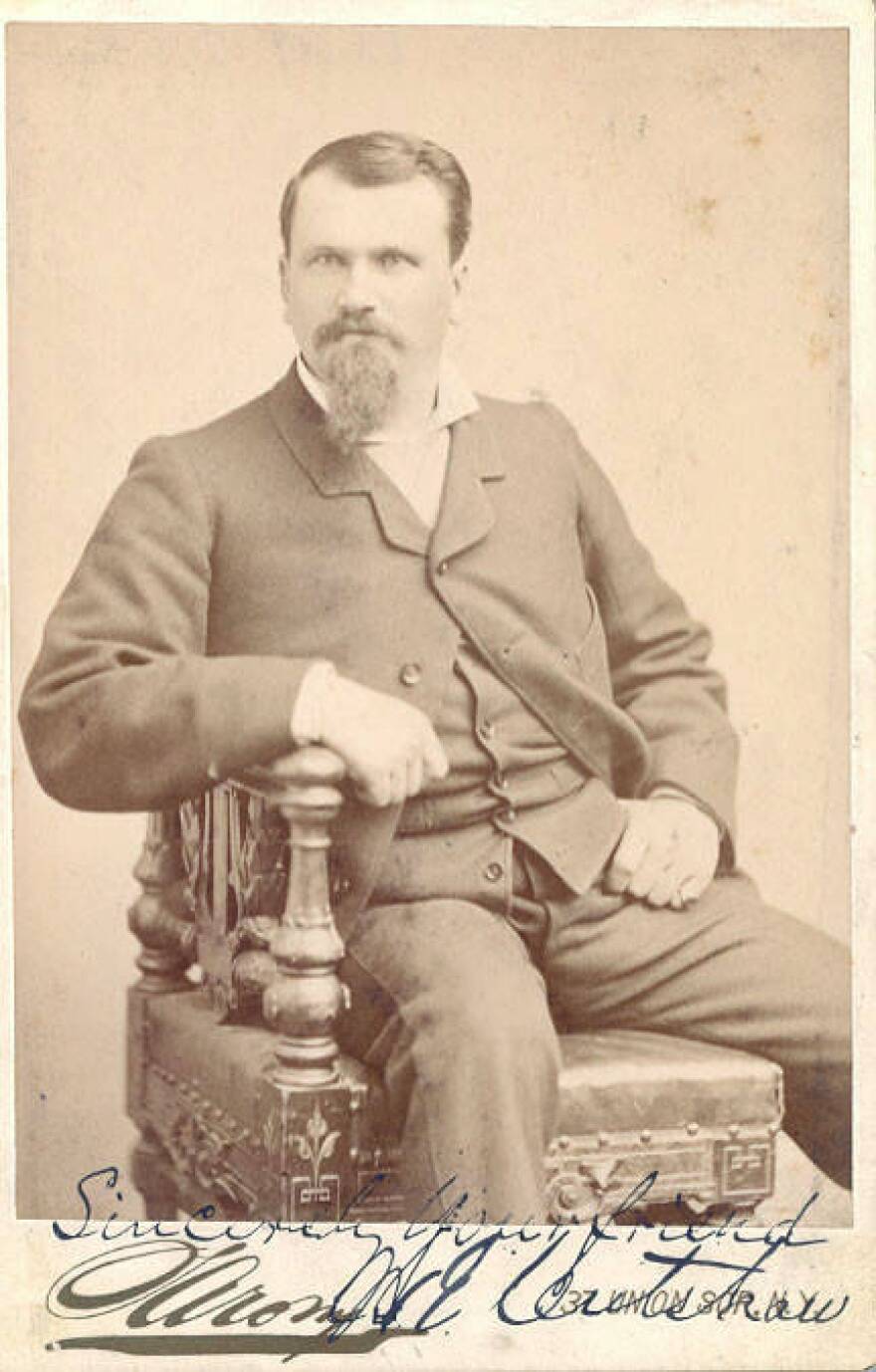

Wilfred Cutshaw, a onetime Confederate soldier, became Richmond’s city engineer in the 1870s. He’s ostensibly responsible for the capital city having a modern waterworks, according to Christina Vida, the general collections curator of The Valentine Museum.

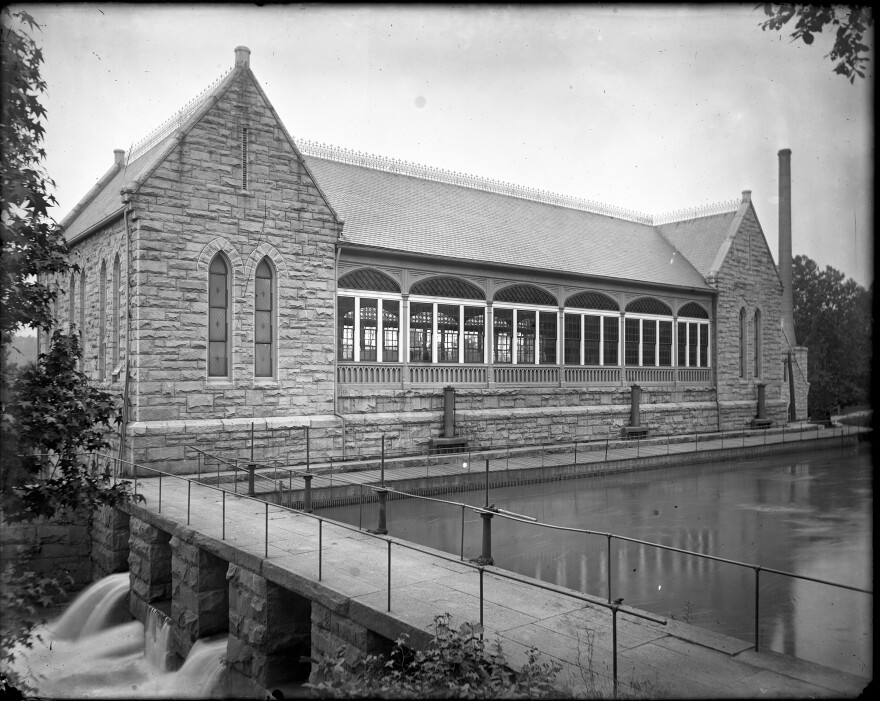

In addition to plotting out the water system, Cutshaw designed the stone and granite Gothic revival pumphouse building in 1881. It was opened two years later and placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2002.

“It is something historically that has been so critical to development, to the economy, to the cost of living, to the ways of living here in the Richmond region,” Vida said about Cutshaw’s work to bring the water system online.

During the 19th century, the original pumphouse was also used by white Richmonders as a place to recreate: There were dances and other events held there, and the surrounding grounds were a place for couples to go for walks.

But by the 1920s, Cutshaw’s pumphouse was becoming antiquated, and calls to bring clean water to Richmonders who weren’t white and affluent were growing. In the 1920s, the city opened a nearby facility, which in 1950 was paired with a new building to prepare James River water for city residents to drink. Those two plants are in use today.

A 2017 city finance document indicated some of Richmond’s water mains date to the 1840s, and another from 2022 said “about 1,000 miles of water mains and 9 pumping stations” are from the 1880s. City communications staff were not able to offer more recent information.

“We're still looking for our contemporary Wilfred Cutshaw to take us a little bit further into the 21st century,” Vida said.

Water requirements and regulations

Under state and federal law, the city is responsible for reliably running clean, potable water through its pipes without interruption. Doing so means following a long list of regulations.

The requirements include maintaining a current emergency operations plan, regular contaminant monitoring, as well as regular reporting on plant activities.

State and federal agencies get involved through audits, like the 2022 EPA report. The federal agency began its latest audit of the water works in September 2024, but officials couldn’t estimate when it would be completed and made available to the public. Agencies outside the city can also intervene when things go wrong to provide oversight and assistance, and can enforce laws and regulations when needed.

“Ultimately, it's the city's job to make sure that they are responding to those areas of concern, and prioritizing needs and allocating the funding needed to make those improvements to the infrastructure where it's obvious that it needs to have some updates,” Roadcap said.

Water quality reports submitted to state regulators since 2022 show a handful of routine bacteria tests throughout the distribution system that came back positive for total coliforms, a category of bacteria that includes the harmful E. coli. That’s not necessarily a bad thing: The coliform umbrella covers a number of other harmless bacteria that naturally appear in the environment. When they do appear, it’s simply a sign that a closer look at the water is warranted, and more tests are run.

Tests for E. coli all came back negative from 2022 to 2024. Subsequent resampling of water supplies after each positive coliform test didn’t show any total coliform bacteria present, let alone any E. coli.

Who’s responsible?

State law governing water utilities caps penalties for violations at $5,000 per day, after the attorney general sues. The State Corporation Commission has wide authority to investigate public utilities, including to determine the “efficiency and economy of operations.” The Virginia Board of Health also has the power to declare certain utilities “chronically noncompliant.”

As the city embarks on compiling an “after action report” and the state conducts its own investigation, the weeklong water crisis is already having repercussions on Capitol Square.

Virginia Senate Republicans have introduced legislation to further regulate water supplies. Sen. Glen Sturtevant (R–Chesterfield) proposed a bill that would have amended Richmond’s city charter to require the head of the public utilities department to hold a degree in engineering or a related field. It was voted down in committee this week.

“From the state direction, we need to look at policies that can make sure that this type of situation does not happen again,” Senate Minority Leader Ryan McDougle (R–Hanover) said recently. “It'll take longer to do the full deep dive into how we got here. But making sure the leadership going forward has a certain level of qualification is one of the things that we think needs to be discussed.”

Last year, the General Assembly passed a bill requiring water utilities to employ someone with a current waterworks operator license. A city spokesperson confirmed the appropriate DPU personnel are in place.

What’s next for Richmond’s waterworks?

In its immediate aftermath, Richmond’s water system failure led to new protocols for visual inspections of the plant, an update of the facility’s emergency contact list and an hourly check-in for staff, Mayor Danny Avula told City Council during a Jan. 13 meeting. An interim director was also put in place to lead DPU.

The mayor said system failures at the plant underscore Richmond’s need to focus more on comprehensive emergency planning and review of critical infrastructure needs. But the most pressing issue is getting answers on what led to the citywide outage.

Avula described a three-phase response, initially focused on an independent investigation into the plant failure and response — which he said would clarify near-term fixes, other factors in need of attention and short-term investments to make.

Richmond signed a $234,000 contract with Kansas City-based engineering firm HNTB on Jan. 21 to investigate its recent water system failure. A final report on the review is expected within 60 days of that announcement.

The Office of Drinking Water — which called the water outage “completely avoidable” in a Jan. 23 report sent to Avula and interim DPU head Scott Morris — is conducting a state-level investigation into the system’s failure. A VDH spokesperson told VPM News that its post-failure probe will be “completed as soon as possible” — but couldn’t share specifics.

“We need to wait to see what that tells us, but I fully expect that there will be findings that there were operational challenges, technical challenges and equipment challenges,” Gov. Glenn Youngkin told reporters after his annual State of the Commonwealth address, which was delayed due to the city’s water issues.

“We've got to wait to do this work, and when we know the facts, then we will chart a course to make sure it doesn't happen again,” Youngkin said.

The second phase of Avula’s plan would analyze the city’s emergency preparedness, including protocols at the water treatment plant and how often the city held emergency response exercises before the crisis.

This could take a couple months, Avula predicted during the January council meeting, adding that work on making system investments and building a stronger emergency response culture would “take place over the next year” or more.

Avula said the water crisis offers an opportunity to take a deeper look at the whole regional water system — while surrounding counties consider becoming less reliant on Richmond’s treatment plant.

In the plan’s final phase, Richmond would work with area localities drawing water from the city’s plant to evaluate regional water resiliency.

He doesn’t know how much the expected repairs and upgrades to the water plant will ultimately cost, Avula told VPM News. To date, his administration has done preliminary reviews on the costs of the recovery and upgrade or replacement of the water plant IT system.

Richmond will also need more DPU workers to provide “additional expertise” in the wake of the crisis, the mayor said.

He praised Del. Rae Cousins (D–Richmond) for requesting $650,000 from the General Assembly to replace damaged system components, but added the necessary updates could take at least a decade and cost a “couple billion” dollars.

Disclosure: Richmond's Department of Public Utilities is a sponsor of VPM. Questions about this article and VPM News’ overall editorial policy should be directed to Managing Editor Dawnthea M. Price Lisco and News Director Elliott Robinson.