Chesterfield County officials unveiled two sites recently slated to house data centers, but residents' questions persist: What will those centers look like, what resources will they require — and what company will even operate them?

“This is in no way a done deal,” Midlothian District Supervisor Mark Miller told residents in late February. Miller added that he hoped the county would be “learning from a whole bunch of other people’s mistakes.”

But over the course of two town halls, county residents peppered Economic Development Authority officials with questions: How much power will they use and how will that affect utility rates? How much water will they need to cool? What about noise?

“The citizens really need to know now,” said resident Bob Olsen. “Because depending on the size of the KW [power consumption in kilowatts] of the data center determines how much Chesterfield County water is going to be needed.”

At the first town hall, Jake Elder, a deputy director with the EDA, said it’s too early in the process to know what the centers’ power consumption would be. Elder also noted the county doesn’t yet know what type of cooling system the centers would utilize.

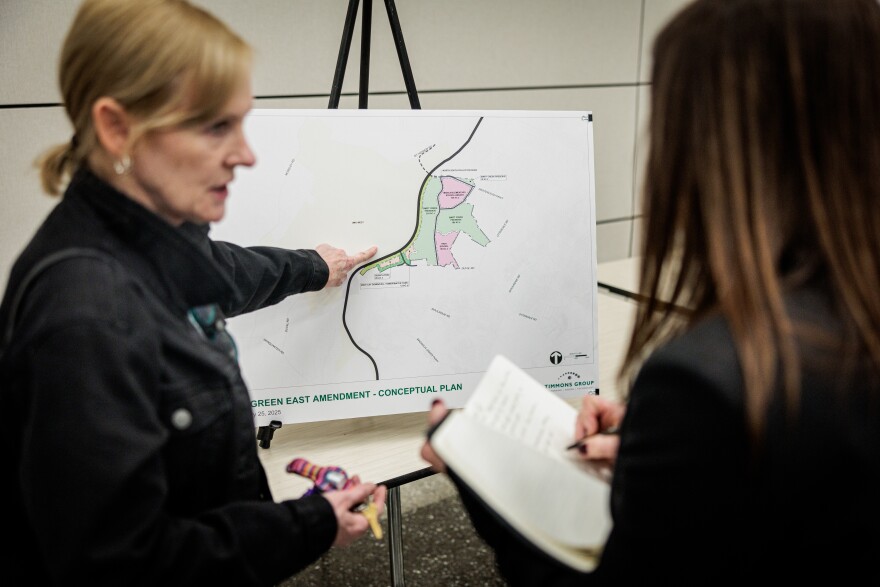

The two plots of land in question are known as Watkins Center — just south of State Route 60 and west of State Route 288 — and Upper Magnolia Green West, west of the proposed Powhite Parkway extension and between State Routes 60 and 360. In total, they comprise almost 1,000 acres.

Officials won’t reveal the name of the company that would operate both sites, but acknowledged that this undisclosed company plans to operate both data centers.

Commercial land use attorney Kim Lacy, who is representing the unnamed developer, said a hydraulic analysis is required prior to zoning approval.

As part of the proposals, the potential developer is offering concessions to make the project acceptable in the community, also known as proffers. Some of those sweeteners include setting noise limits of 65 decibels during nighttime hours, paying for local infrastructure upgrades and covering water and wastewater costs.

As for the effect on electricity rates, Alex Rendon, the government affairs representative for Dominion Energy, said to the crowd at Midlothian High School that “we have rate classes for industrial customers, commercial customers and residential customers” which are set by state regulators.

“We can confidently say that heavy users of power do pay their fair share of what the power generation costs are,” he added.

Energy demands a concern for some residents

Dominion projected that electricity bills are likely to increase under the combined pressures of extreme load demands of hyperscale facilities, including data centers, and a changing electricity grid. The utility detailed a possible 50% increase in residential bills by 2039 in a 15-year planning document filed with the State Corporation Commission last year.

The SCC opened a case on impacts to customers, utilities, infrastructure and rates in late 2024 in response to the proliferation of data centers and other hyperscale energy users.

“This new load could surpass a provider's current peak load requirements for its entire system, creating issues and risks for electric utilities and their customers that have not heretofore been encountered,” commissioners wrote in an announcement of a December conference on the subject.

Then, during the General Assembly’s regular session, state lawmakers considered a measure that would have required the SCC to rule on whether non-hyperscale ratepayers “unreasonably subsidize” grid improvements spurred by data center growth.

The bill, sponsored by state Sen. Russet Perry (D–Loudoun), died at the last possible stage of consideration when a group of bipartisan lawmakers from the House of Delegates and Virginia Senate couldn’t come to an agreement on language.

However, another measure that could impact the developer’s planning process did pass both chambers. If signed by Gov. Glenn Youngkin, Del. Josh Thomas’ (D–Prince William) HB1601 would allow Chesterfield to require a site assessment on impacts to water and wastewater, forests, agricultural land, parks and historic sites on the property and neighboring parcels.

It may also require the county to ask for noise impact assessments on nearby schools, hospitals and residences.

Chesterfield EDA officials have said that over 20 years, a $1 billion data center would generate a bit more than $71 million in combined tax revenue.

Some Chesterfield residents said they were concerned that they could be looking at the beginning of a massive influx of data centers in the county, the kind Loudoun County has seen.

“We saw in Loudoun County, it was so fast, one after another,” said Elizabeth Zizzamia, a Midlothian resident who grew up in Loudoun County. “What kind of assurances do we have as a community that every wooded parcel is going to become another data center that is going to pollute our water, our air and use our electricity?”