Bon Air Juvenile Correctional Center in Chesterfield County is the last maximum security youth prison Virginia.

Resident Sage Williams came along for a media tour earlier this month to help explain some of the programs there.

“They sit down with you and get to the root or core of the problem,” he said. “Instead of throwing you behind a door when you act up”

Williams is president of the newly formed student government association at Bon Air. He and a few other residents on the tour were dressed in shirts and ties. Williams is one of about 200 young men and women housed here. But it was built to house almost 300. It’s a large building, with cinder block walls and windowless rooms. Counselling takes place inside empty cells, as heavy doors slam in the background.

Criminal justice experts say this type of facility isn’t ideal for rehabilitating young people who are caught up in the criminal justice system.

“Forty years ago, thirty years ago they thought windows and space and looking outside was a distraction,” said Andrew Block, director of the Virginia Department of Juvenile Justice.

“And now the current thinking is having natural light and things like that helps stimulate brain activity and performance and engagement,” Block said.

This week the Virginia Department of General Services will recommend a location for a new Juvenile Correctional Center in Central Virginia. The plan follows a multi-year overhaul of the state’s juvenile justice system.

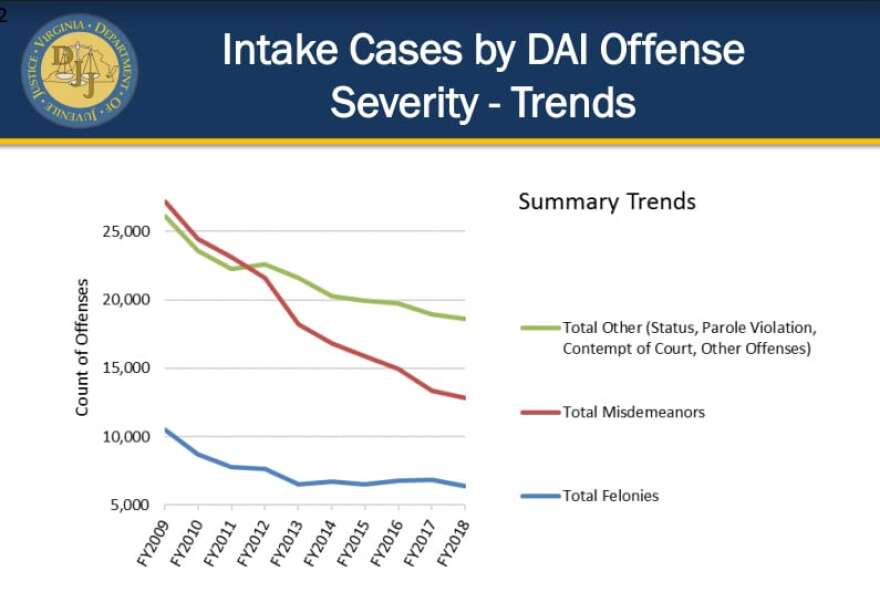

The Department of Juvenile Justice oversees people under the age of 21 who were charged with a crime before they turned 18. Following national trends, Virginia’s juvenile prison population has declined. That’s allowed the state to close outdated youth prisons, including Beaumont Juvenile Correctional Center in 2017, and use the money it saved for programming.

“We’ve been able to stand up a huge array of evidence-based programs and new services that kids across the state didn’t used to have access to,’ Block said.

Block credits new sentencing guidelines with reducing the youth prison population from about 600 four years ago, to a couple hundred today. Judges are less likely now to send kids away to serve long sentences. And a lot of lower-risk offenders have been moved to smaller detention centers in their own communities.

What the department has planned is a 60-bed youth correctional center in Hampton Roads and a 90-bed facility somewhere in Central Virginia to replace Bon Air. Block said they both will have treatment space and plenty of natural light.

“It will have colors and stimulating environment that we don’t have so much of,” Block said. “We’re trying to do the best we can with what we have right now.”

Another Way

Despite the state’s progress, some groups oppose the idea of building a new youth prison.

“When you send kids to facilities, the conversation starts, you’re on your way to the big house. You’re on your way to prison,” said Jerry Lee, a former prisoner and an advocate for youth offenders in Virginia. Lee was on a tour last month in Richmond with the group RISE for Youth, which advocates for alternatives to youth incarceration.

“They’re not thinking about their algebra homework,” Lee said. “They think about the rough stuff. How am I going to protect myself in prison?”

RISE for Youth wants to see much smaller facilities than what the Juvenile Justice Department has planned. The tour included a two-story home, which the group said could be secured to house ten to 15 youth offenders.

“If we can open up these type of houses, the only thing they want to do is, how can I own my own?” Lee said. “How can I sink my feet into my own carpet? How can I work on my own sink?”

“And we want to get as close to home and as close to a home as possible.” said Valerie Slater, director of RISE for Youth.

In 2012, New York City moved away from large, outdated youth prisons to smaller facilities. They were as small as six to 18-beds, located in offender’s home communities. The city saw declines in youth arrests and some better educational outcomes. Slater believes Virginia could also make this model work.

“They are receiving the rehabilitative services they are needing,” Slater said. “They are being held accountable. But they are also learning some amazing things about what does it mean to be a part of a functioning family.”

RISE for Youth has been lobbying lawmakers to adopt these alternatives. But it hasn’t been an easy sell.

“I do not think there will ever be a time where there will be no facility that is needed,” said Republican Senator Ryan McDougle (R) . He said the department has already reduced Bon Air’s population to only the most serious offenders.

“We have taken the model of moving kids to the smaller detention facilities that are in their communities,” he said. “And this is the continued direction to do that. To have two small facilities. One 60 beds. One 60 to 90 beds.”

High Recidivism

One area the department is not seeing improvement is re-arrest rates. The numbers are still grim. Between 2012 and 2016, about half of youth were re-arrested in the year after their release. But as the state continues making changes, Direction Andrew Block expects these numbers to shrink. He said at Bon Air educational achievement is up and aggressive behavior is down. And it’s all happening inside an outdated prison, with what he says are, at least on paper, the most challenging kids in Virginia.

“If success in here and safety and educational progress are kind of leading indicators of what we hope to expect in terms of recidivism, I’m feeling pretty good about where we’re at,” Block said.

Block doesn’t think he can make those programs as successful in the kinds of facilities RISE for Youth would like to see. But ultimately, it will be up to the General Assembly to decide what a Central Virginia Youth Detention Center looks like. And RISE for Youth will continue to push for a seat at the table when those discussions take place.