Perfect

To Dai Vernon, Amador Villasenor was a lucky draw, like turning up three aces in the last hand on a losing night. To the cops in Wichita, who had searched for him for three long years, Villasenor was a gambler, a cardsharp, a thief, and a killer.

Though perhaps not a first-degree murderer. Villasenor swore he had acted in self-defense, and the police and his jailers believed what he had to say. The distinction was a technicality, maybe, but his freedom depended on it. Villasenor had, after all, taken a man's life. He had confessed to shooting one Benito Leija and leaving him to meet his maker in the grit of a Wichita alleyway back in the red-hot summer of 1929. He said he had even watched as Leija -- like himself, a young Mexican in his twenties, a gambler well accustomed to the feel of cards and dice -- had staggered off the sidewalk outside Manuel Garcia's poolroom in Wichita's North End, contemplating his speedily approaching end. Villasenor had jumped in his car on that July evening and bolted out of the city as Leija pitched forward from his knees into a pool of his own blood.

Vernon, who had just come to Wichita, knew little of what had landed Villasenor in the city's Sedgwick County Jail, where he was meeting him on a wet winter night during the first gloomy week of February 1932. The crime had happened long before Vernon arrived in Wichita and it didn't really interest him. To Vernon, Villasenor's predicament was a scrape like a million others, a "gambling mix-up," he called it. Vernon certainly wasn't one to make a hobby of murder. That was not his line.

What roused Vernon on this chilly evening was the possibility he might learn something from Villasenor he could use in his magic. Vernon was a magician, an artist. Magic was his obsession. It was what he cared about more than anything else. For three decades, Vernon, now thirty-seven, had been consumed by magic. At times, it possessed him. It was what he puzzled over, theorized about, dreamed of.

Magic would keep Vernon up for days at a time with no thought of food or rest. Magic softened these hard times of the Depression. Magic made his dull days cutting silhouettes in a department store in this wheat-and-oil town passable. He was a world away from the ritzy Park Avenue soirees where he had once been the featured attraction, but magic made even that bearable. It was what allowed Vernon to walk blithely into a jail to shake hands with a killer. Vernon would smile and follow the devil himself if it meant he could bring back something, a sleight, a ruse, a line of patter, that he could use in his art.

In the Twenties magic had offered audiences a cocktail of glamour and glitz, elegance and escape, to chase away the humdrum workaday world. To most of the great illusionists of that golden era, bigger was better. Magic, to those veterans of the slam-bang vaudeville tours, meant stage spectacles on a grand scale. The tuxedoed, ministerial Howard Thurston, then considered the most popular magician in the world, offered up his portentous Wonder Show of the Universe with ever-more elaborate levitations and disappearances, including the "Vanishing Whippet Automobile," packed with seven gorgeous young beauties. Horace Goldin, known as the Whirlwind Illusionist, jammed so many effects into his dizzying act that he had stopped speaking on stage altogether lest he slow down the pace. "Silence is Goldin," a British competitor had quipped. But to Dai Vernon, spectacle had little to do with magic. To Vernon, the magic was not in the size of the stage or the number of tricks on the bill or the box-office receipts.

Vernon had first started popping up at New York's fabled magic shops around the end of World War I. He was from Canada, dashing and cultured, and he handled cards with a gentle grace, coaxing such startling effects from them that even the most experienced magicians were flummoxed. In short order, he was ushered into the hallowed back rooms where only the most elite practitioners of the ancient art were allowed to gather.

Quickly, quietly, he had begun to steer his art in a new direction. He was as different from an old-style illusionist as an Impressionist was from a sign painter. Rather than larger and faster, he preferred to make magic that seemed more casual, and thus more natural. And as he became more well-known, a small group of nimble-fingered sleight-of-hand artists, who came to be dubbed the Inner Circle, gathered around him. They were a quiet band of artistic assassins killing off the old Victorian ways of magic. Vernon was the Lenin to the rest of these revolutionaries. He became magic's Picasso, its Hemingway, its Duke Ellington.

Vernon had little interest in the old stage ruses. He believed that sleight of hand and psychological subtlety far surpassed the hidden mirrors and wires used by conventional illusionists. To him, the proper stage for real magic was not the expanse of the vaudeville boards, but the unadorned human hand, held out just before his spectators' eyes. And the best props were not floating women or disappearing automobiles, but bits of string, colorful silks, cups and balls, coins and cards. Always cards.

Cards were Vernon's first love. They were the choice instrument for his audacious style of magic. He moved away from the pick-a-card tricks that always started the same way, preferring instead to have people merely think of a card without touching the deck. Then he would look them in the eye and tell them the exact card they were thinking of. He replaced the dull Victorian patter with sharp, modern tales peppered with slang. With a rakish grin, the smoke of his cigarette curling up around his dark eyes, Vernon would deftly maneuver the cards with his long, elegant fingers, improvising with them the way a jazz musician might with his cornet, beginning an effect without knowing exactly where he was going to take it.

The Wichita jail was an imposing building that held a small town's worth of prisoners, over eight hundred, from murderers down to bad-check writers. Since the Depression had tightened its grip and winter had settled, a new class of prisoner had begun to appear -- hobos, drunks, and other down-and-outers looking for a hot meal and a warm, dry place to stay the night. Vernon's friend Faucett Ross, a fellow magician who had gotten the tip about a gambler in the lockup who was a whiz with a pack of cards, went in with him. After Ross gave the inmates some smiles by doing a few tricks, the guards went down to the cell block to fetch Amador Villasenor.

No wave of a wand or abracadabra could make the Depression disappear. By the Thirties, magicians were hard-pressed to keep themselves from vanishing. Audiences were smaller now and with the advent of the "talkies" it was much harder to captivate them. For just a quarter, there was the roaring King Kong astride the Empire State Building, his paw wrapped around the scrumptious Fay Wray. How could magicians compete with movies? Back in the heyday of vaudeville, the great magician T. Nelson Downs had dazzled thousands around the world with his "Miser's Dream," pulling a seemingly endless supply of coins out of the air. But now in the Depression, audiences were longing for "Pennies From Heaven." Downs was retired and friends were sending him postage stamps in their letters to be sure he could afford to write back. After the stock market crash, even Vernon's lucrative engagements for the Astors, the Vanderbilts, and the Schwabs at their swanky parties and Long Island country clubs began to disappear. With few prospects, he and his wife, Jeanne, with their young son, Ted, in tow, had left Manhattan and hit the road.

Vernon became an artist in exile, aimlessly making his way across the country. He supported his family by cutting silhouette portraits, an improbably reliable profession despite the times. In the summer of 1931, the Vernons were in Virginia Beach when they decided they might as well head west. After reading in the newspaper about the gambling resort of Reno, they decided to work their way across the country to Nevada to see what all the fuss was about. By the middle of July, having braved the parched countryside of Kansas and Oklahoma, they rolled into Colorado Springs.

After the Dust Bowl, Colorado Springs was a delightful oasis in the Rockies. It was cool and instantly restorative. Vernon was thrilled to find master magician Paul Fox working a little carnival there, and he and Fox struck up a fast friendship. Vernon set up his silhouette stand at Manitou, the posh resort at the foot of Pike's Peak. At summer's end, the Vernons moved on, not to Reno, but to Denver now. There they met up with Faucett Ross, who invited them to come to live near him in Wichita. Ross had told Vernon he could cut silhouettes at the exclusive George Innes Department Store, the city's finest.

"Show these fellows a couple of those things you were doing with the cards," the guard told Villasenor when they brought him up from the cell block. Villasenor was younger than Vernon, about twenty-nine. He had a broad, roughly framed face and thick, black hair. Soft-spoken, with hesitant English, he seemed eager to please the jailers with this demonstration. He was an experienced sharp with several sleights in his repertoire, moves to "get the money," as the gamblers said. He began by showing the magicians a slick one he had worked up to beat the game of monte, not the well-known three-card short con of riverboat and fairground fame, but a card game popular among the Mexican workers who had been brought up north to labor in Wichita's slaughterhouses and train yards. Vernon watched intently. He could see that Villasenor was a professional, but he could also tell that the Mexican was no great virtuoso. His card handling was workmanlike, good for fooling these jail guards maybe, or drunken marks at a roadhouse, but he was not a genuine sleight-of-hand artist. After demonstrating his monte move, Villasenor showed off a couple of other sleights -- a slip and a shift. Then, he moved on to his false deals. Vernon saw everything coming.

From the time he was a boy, when, by accident, he discovered how his father had accomplished the first true magic trick he ever saw, Vernon had been steeped in secrets. Magicians live with secrets, naturally, but few of them ever come to fully understand their deepest intricacies. Vernon did. Early on, he came to see that the secret behind the trick wasn't the only ingredient needed to make great magic. But a secret was often the starting point. So as he became obsessed with magic, he also became obsessed with secrets. When Vernon was still in knickers, rambling around Ottawa on his bicycle, he developed a drive to track down those who held the secrets to his art. If he heard a rumor about some boy who could make a coin disappear, Vernon would jump on his bicycle and ride for miles until he found him. If he saw con men at the racetrack, he would skulk around for hours, deflecting their threats, until he discovered just what they were up to. His life became a quest for secrets.

The deepest secrets in magic, he discovered, were usually found in the skillful, fearless hands of those Vernon called the gamblers -- the cardsharps, the broad tossers, the dice mechanics who could subvert any game they played without the slightest hesitation. Vernon came to see them as the greatest magicians of them all. He had found some of the cardsharps' secrets in a mysterious book called The Expert at the Card Table, a bold volume he took as his bible but which most other magicians shied away from, dismissing it as indecipherable. Still other secrets he learned in person after tracking down gamblers. Magicians had been borrowing sleights from card cheats for hundreds of years, but Vernon had an unprecedented knack for prying the cherished tricks of the trade out of these closed men. He was tenacious, and he could handle people as well as he handled cards. He laced his tricks with devastating moves taken from the card table -- false shuffles, palms, card switches, and many more. Other magicians couldn't follow them. They came to hold Vernon in awe.

Of all the gamblers Vernon learned from, he was probably most enamored of the false dealers. They were the elite among the cardsharps. The second dealers, called Number Two men in gambling slang, could smoothly slide the second card off the deck and make it look exactly like they were taking the top card. The bottom dealers -- subway dealers, they were called -- could do the same with the bottom card. These sleights required years of practice to master, and they could be devastating in a card game. Vernon sought these men out diligently. Their techniques were rare in magic, and invaluable, allowing him to do tricks that even other accomplished card magicians thought were impossibilities.

Still, there was one master among these false dealers, with one great secret, that had always eluded Vernon. It had eluded everyone. Even among the most gifted of the cardsharps, this virtuoso remained just a rumor, a fairy tale. Vernon had heard the tales over the years, of a cardsharp who could pick up a deck that had been fairly cut according to the rules of play, and deal out any card from it that he wanted. With a single deal from the center of the deck, this cardsharp could make all the rules and the very laws of chance itself vanish. Just like a magician.

The faint murmurs about the center dealer, who supposedly lived somewhere in the Midwest, swirled into myth. From time to time, Vernon heard new reports of this unparalleled master, but in the end he had always dismissed the vague tales as hokum. He came to agree with those who considered such a feat beyond reach, and removed the center deal from his list of obsessions -- until he got to the county jail in Wichita.

"You've been a gambler all your life haven't you?" Vernon asked Villasenor as their visit wound down. After the Mexican had finished showing what he could do, they had started to chat. Sure, Villasenor agreed, he had been gambling pretty much all his life. "Well," Vernon continued, "have you ever witnessed anything unusual…? You've played cards all your life, have you ever seen anything you don't understand?"

Villasenor's English may have been a little shaky, but he didn't hesitate now as he answered the magician. "In Kansas City," he replied immediately, a surge of excitement in his voice, "I see a fella. He deals cards from the center of the pack...."

Suddenly, the magician was no longer just looking to liven up a stormy night. Ross was stunned to see how Villasenor's words electrified Vernon. Indeed, the way the Mexican announced this news, so boldly, made Vernon think it could be the truth. He began firing questions, asking Villasenor again and again how the man's deal had looked. "Perfect," the gambler answered every time. Perfect. It was a word Vernon always shunned. Yet Villasenor threw it down confidently, as he would a winning hand or a pair of loaded dice. Perfect.

The end of his session with Villasenor marked the start of Vernon's search for this secret that had been beyond his imagining, a secret held by a man he would come to consider the greatest sleight-of-hand artist of them all. For decades, he would tell other magicians about it, a story many of them would dismiss as a tall tale. It all began in a Wichita jail, Vernon would say. But the story of his great quest didn't begin on that wet, raw night in Wichita. It started much earlier, in Canada, where a small boy came upon some playing cards strewn along the railroad tracks. He would pick them up and use them to create his first tricks, devilish tricks like no one had ever seen before.

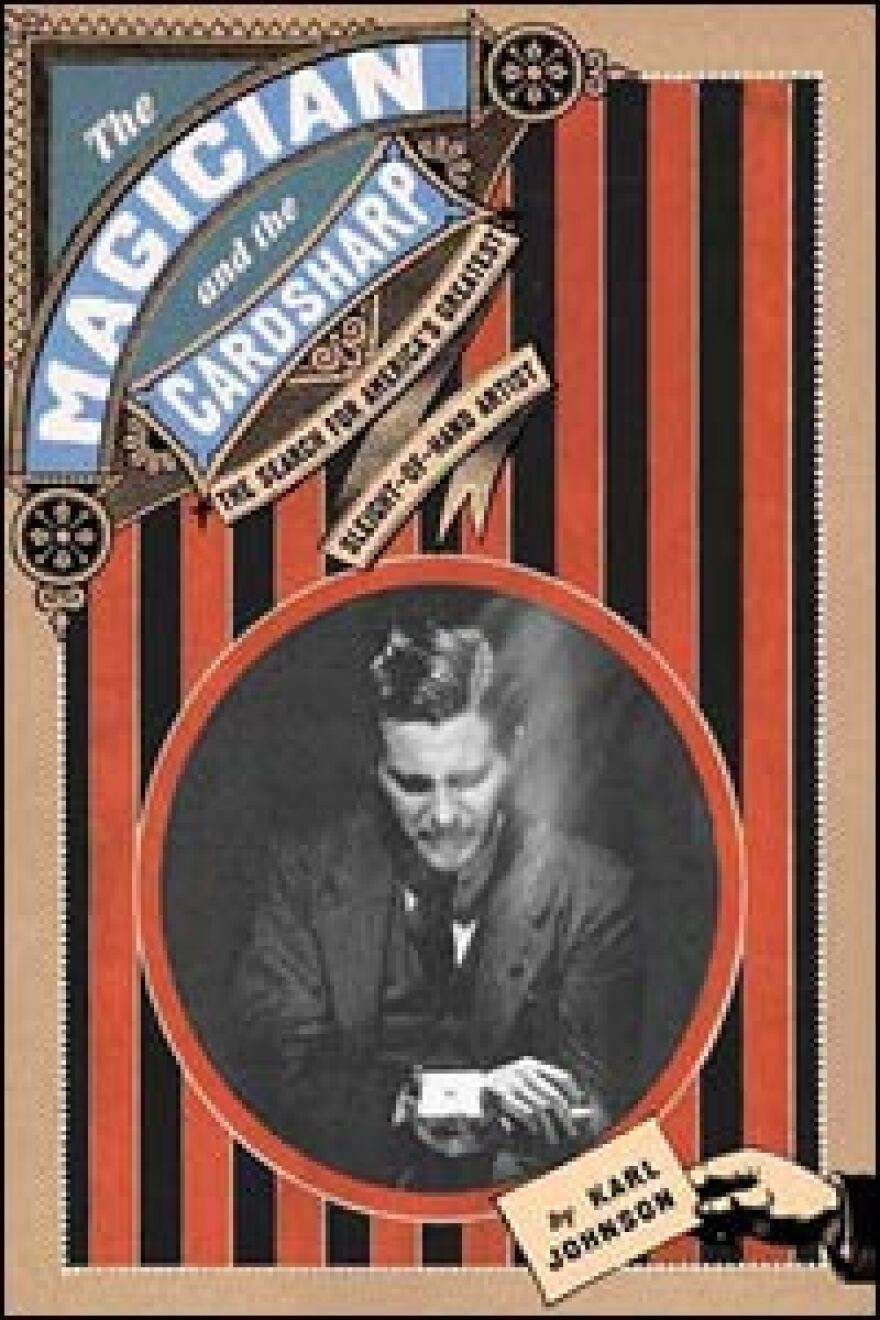

Excerpted from The Magician and the Cardsharp Copyright © 2005 by Karl Johnson.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDM3NjYwMjA5MDE1MjA1MzQ1NDk1N2ZmZQ004))