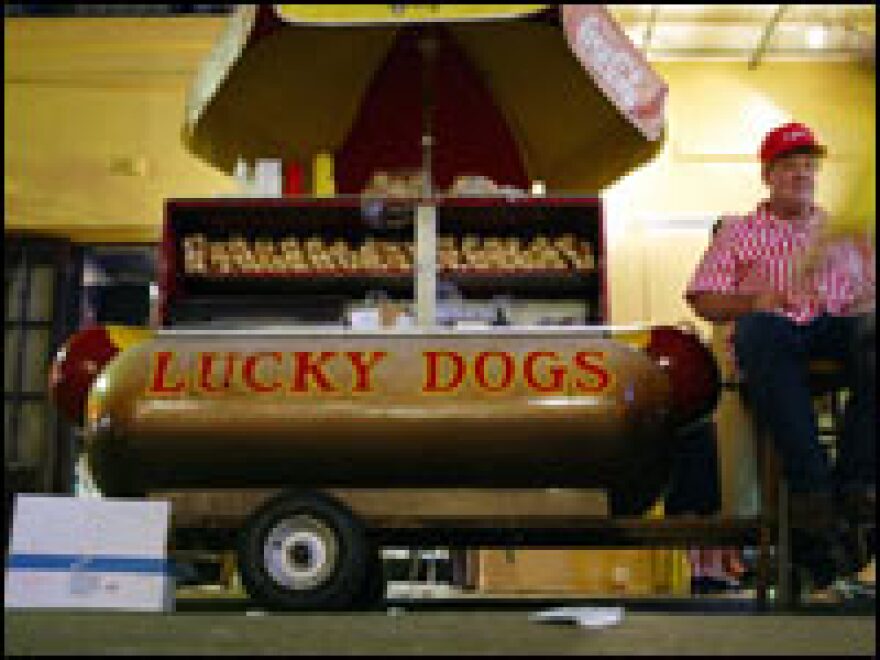

What follows is an excerpt from an essay by John T. Edge, originally published in the Oxford American in 1998. Edge writes about his stint as a hot dog vendor for Lucky Dog, the company immortalized in John Kennedy Toole's comic novel A Confederacy of Dunces. After an encounter with Lucky Dog Manager Jerry Strahan, the author eventually took to the streets of New Orleans to learn the trade.

December 30, 1997

And so it was that, approximately one year after my first encounter with Jerry, I found myself back in New Orleans. Attired in a red-and-white-striped shirt and an official-issue Lucky Dog cap, I stood in the heart of the French Quarter at the corner of Bourbon and St. Louis streets, listening to a fellow vendor's harangue.

Drink up you slobs! You know the routine. Drink. Stumble. Dance. Eat a Lucky Dog. Go home...What's the matter with you people? You're sober, you pitiful pieces of shit! Drink tequila. Smoke dope. Get the munchies. Eat a dog! Let's go!

It is a little after 9 o'clock on a frigid Tuesday night and Adolf, a former Ole Miss student, is just a wee bit upset. With New Year's Eve only a day away, he had hoped to be raking in big commissions on the sale of quarter-pound Lucky Dogs at $4.25 and smaller, regular dogs at $3.25. Instead, business is down. According to Adolf, it is all because the crowd is too sober. Lucky Dog vendors pray for drunks like farmers pray for rain. Drunks do not normally debate the relative merits of paying $4.25 for a turgid tube of offal meat, fished from the steamy depths of a hot dog-shaped cart, and cradled in a gummy bun that threatens collapse under a molten mountain of mustard, ketchup, chili, relish and onions.

For drunks, Lucky Dogs are not so much food as fuel, and drunks need fuel if they are to survive a night of debauchery in the French Quarter, an area that Ignatius, perhaps the most famous vendor ever to peddle a dog, claimed "houses every vice that man has ever conceived in his wildest aberrations, including, I would imagine, several modern variants made possible through the wonders of science."

With business still at a crawl, Adolf, a onetime Nazi who says he has mellowed and now just likes to think of himself as a racist, asks me to look after things as he goes in search of a bar that will let him use their bathroom. I begin poking around inside the cart. Self-contained restaurants of a sort, the carts are equipped with sinks, steamer compartments, iceboxes, propane tanks, and prep tables — all enclosed within a seven-foot-long, 650-pound metal wienie-on-wheels. As I peer into the inner workings, I begin to understand Igantius' befuddlement when he exclaimed: "These carts are like Chinese puzzles. I suspect that I will continually be pulling at the wrong opening."

When Adolf returns, I wander up the street in search of a bit more on-the-job training. At the corner of Bourbon and St. Peter, I find Rick. Nattily attired, pleasant and well spoken, Rick is the antithesis of Adolf. As drunks stumble out of the Krazy Korner Bar, Rick jingles the change in his pocket and calls out: "Lucky Dogs. Get you Lucky Dogs here. Buy one at the regular price, get a second one at the same price!"

While we are talking, a black man in a white satin jump suit stops in front of us and screams out, apropos of nothing, "That Tom Jones is a bad white muthaf--a!" His attempt at doing a split in the middle of the street is unsuccessful. When he topples, I move on.

I wade deeper into the Quarter. At the corner of Bourbon and Orleans, David is sporting a soiled Santa hat and barking like a carny. "I don't want your first born!" he shouts. "I certainly don't want your ex-wife! And I probably don't want your college grades! But I do want your tips!"

Like many of the twenty-odd vendors working Bourbon Street on a typical night, David, a veteran of two weeks, sees Lucky Dogs as a way station, not an occupation. "I'm a commercial fisherman by trade," he says. "But I've done my share of street vending. Worked the carnival circuit too. I love it out here...Out here I'm just David. No past, no future --just passing through."

It's now about eleven o'clock and though I am enjoying the spectacle, I am not doing much work. Most carts are already fully staffed by two vendors. Fortunately, soon after I leave the corner of Bourbon and Orleans, I meet up with Jerry who tells me that Alice is in need of help and is willing to share her cart with me for the next few nights.

When I first encounter Alice, a woman of great girth but few teeth, she is standing at the corner of Bourbon and Conti, opening and closing the cart's steamer compartment, fanning wiener fumes across the street in hopes of luring passersby. She is having little luck.

"It's still a little too early. They're drinking now, but they're not quite drunk enough. They'll come around; they've got to...I only cleared 65 dollars yesterday," she says, a touch of desperation in her voice. "We've been waiting too long for this – suffering through December, waiting for New Year's and then Mardi Gras."

After more than fifteen years on the job, Alice, knows the street. And more importantly, Alice knows her drunks. Over the course of the next few hours she shows me the ropes and mentally prepares me for what will happen tomorrow night. "It's gonna be hell on New Year's Eve," she warns. "This isn't a party; this is a job. And you damn well better treat it that way."

Alice runs a well-stocked cart. In addition to the company-issued condiments like mustard, ketchup, chili, onions and relish, Alice offers her patrons a little Tony Chachere's Creole Seasoning — "for a taste of New Orleans" — as well as pickled jalapeno peppers. And, for those in search of still more heat, Alice will douse your Lucky Dog with her own special blend of hot sauce. "It will light your ass up," she says, her face creased by an enormous smile.

During the lulls between customers, Alice and I gaze at the slovenly promenade. The few customers we serve retreat just a few feet before trying to stuff the oversized dogs in their mouths. I watch, disgusted, as chili and relish plop from the back end of their buns and onto the sidewalk like dung from the business end of a horse. But, as one o'clock passes, the lulls become shorter. Soon a line has formed and the rush is on.

By two in the morning Alice and I are working as one. I make the dogs. She makes the change. And when she flails away at a gawky drunk who dares curse me for being too slow, I attempt to hold her back. Fortunately for the drunk, the crowd parts and he vanishes into the lurch.

Meanwhile, with the horde pressing down upon us, Alice and I scramble to keep up with the orders. In a rush of syllables and slobber, two college freshmen, down to their last dollar, plead for a bun full of chili, and then, as if by divine intervention, scrounge together the $3.25 needed for a regular dog. With my back to the crowd, I lean into the cart, reach for the tub of relish, and begin spooning it on their dog. I grab a pair of tongs and begin to pile on a mess of onions. When the soberer of the two leans in and mumbles "Gimme more chili on it will ya?," I feel the spray of spittle and liquor on my nape. Rather than break the rhythm of work to wipe away his request, I ladle on the chili and turn to take the next order. Alice collects the clump of bills that he shoves in her face.

By half past two, our pockets are bulging from the night's take. When the pizza place across the street closes at three o'clock, we suddenly have six customers in line. "They've got no choice now!" Alice cries with delight. "Now we've got 'em." We may well have them now, but thirty minutes later the street is starting to clear. At a quarter 'til four, Alice decides to call it a night. Ketchup splattered and bone tired, I head on.

Originally published in the Oxford American 1998.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDM3NjYwMjA5MDE1MjA1MzQ1NDk1N2ZmZQ004))