Few people outside Africa seem to understand the scale or the epic gravity of what is happening there. When I talk to people at home about the pandemic, I get the sense that they feel a dying African is somehow different from a dying Canadian, American or German — that Africans have lower expectations or place less value on their lives.

That to be an orphaned fifteen-year-old thrust into caring for four bewildered siblings, or a teacher thrown out of her house after she tells her husband she is infected — that somehow this would be less terrifying or strange for a person in Zambia or Mozambique than it would be for someone in the United States or Britain.

And so I wanted to tell their stories — to tell how they want to go to high school, or build up a small taxi business, or meet their grandchildren. When people in Tanzania or Botswana find themselves fighting governments — their own and in the West — and multinational pharmaceutical companies and their own families and the neighbors who isolate and fear them, that is every bit as bizarre and daunting for them as it would be for you and me. I have met the beauty queens and the soldiers and the young lovers and the scientists who live with AIDS in Africa, and I know that the only way that they are different from me is that they have the misfortune to live in countries that are economically and politically marginal — that they are black and they are, quite often, poor, and so their lives can slip away unremarked.

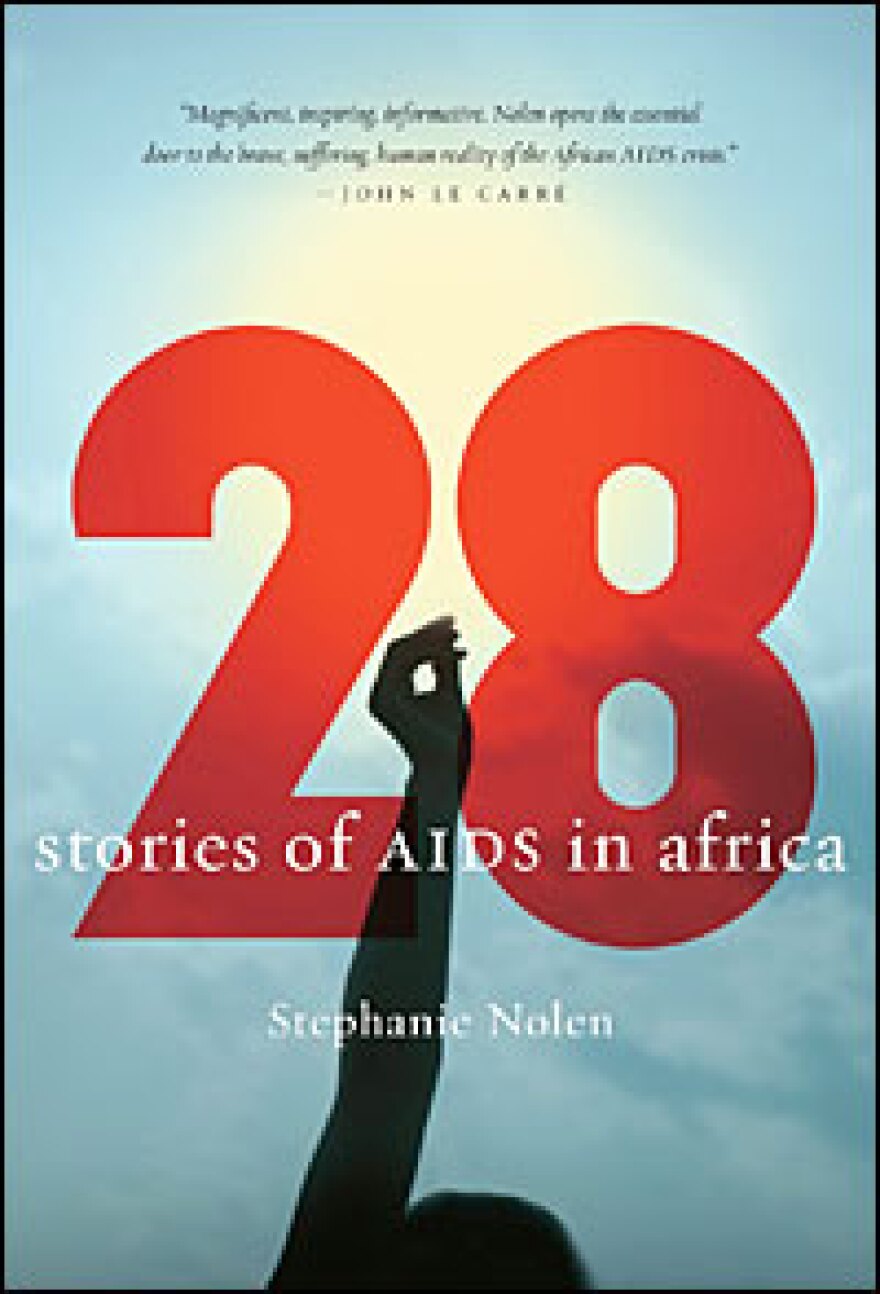

I can't tell every story. I decided to tell twenty-eight — one for each million people infected in Africa. Their stories explain how the disease works, how it spreads and how it kills. They explain how AIDS is horribly, inextricably tied to conflict and to famine and to the collapse of states. They explain how treatment works, when people can get it and how the people who can't get it fight to stay alive with virtually no help and no support.

Let me say, here, a word about numbers. This book could equally plausibly be called 26 — or 30. The data collection on the number of people living with HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa is extremely weak. Many countries draw their statistics only from HIV tests at prenatal clinics, because that's the one time adults reliably come into contact with the health system. But those numbers can be artificially high compared to the overall population, because by definition pregnant women have had sex. A few countries have done door-to-door surveys, and these are more reliable, but people who know or suspect they are infected are much more likely to decline to be tested by the surveyor who knocks at the door, even when promised anonymity. So that pushes the numbers in those surveys down. Many nations lack the skilled people to accurately process and maintain these kinds of statistics, and in those countries, the UN agency responsible, UNAIDS, is guessing, too.

Still, today, only an estimated 10 percent of those who have the virus in Africa have actually been tested for it. Meanwhile, national governments have played down their infection rates — not wanting to scare off tourists or foreign investors — at the same time that international agencies have sometimes inflated them, out of a desire to attract more attention and more funding. In recent years UNAIDS has revised its infection numbers for most African countries downward (while a few shot up); part of that decline is the result of people dying, and part of it of more reliable statistics.

The latest epidemiological survey for the continent gives a range of twenty-five to thirty million people with the virus. My own feeling, after nine years of watching the African pandemic unfold, is that the figure twenty-eight million in Africa is conservative.

Again and again, I travel to areas where the estimated prevalence is 15 percent, but it seems obvious from looking around that the rate of infection is higher; or I speak to doctors and government health officials who have just done new surveys and found much higher numbers than they expected. I suspect that when accurate survey methods finally reach into rural areas and all segments of the population, the figure will be still higher.

This is, of course, on some level immaterial. The African epidemic is as much of a crisis with twenty-eight million people infected as it is with twenty-three or thirty-three million. The inaction of the previous two decades is ample proof that numbers alone, no matter how high, are not enough to motivate the United States to respond in any adequate way to the crisis.

Some of the people in this book I have come to know well, and come to call friends, and I have followed their stories for years. Others I met only once, over a day or two in their shattered villages, and so I can tell their stories only as a snapshot as their lives nraveled.

Some of these stories show us what success in fighting AIDS looks like, and others tell us how desperately far we have to go.

Some make for painful reading. Many of the people I meet wage a daily struggle to stay alive. All of them have suffered a level of loss of which I can barely conceive. They have been betrayed by their lovers and their families and their neighbors and their governments. AIDS has robbed them of much more than health.

And yet each day in my travels in these worst-affected countries, I meet people caring for their sick families and their neighbors, fighting drug companies and their governments for treatment, sheltering their orphaned siblings, overcoming shame and fear with breathtaking bravery. Along with all the pain and all the needless loss, theirs are stories of triumph and resilience, and they give cause for hope in the most unlikely circumstances.

People ask me all the time why I do this job, when "it must be so depressing." Here are twenty-eight of the reasons why.

From 28: Stories of AIDS in Africa by Stephanie Nolen, reprinted with the permission of Walker & Company, 2007.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDM3NjYwMjA5MDE1MjA1MzQ1NDk1N2ZmZQ004))