David Beckham is a hard man to hate. I should know. As a lifelong West Ham United fan, I've been trying to loathe him for years.

Distaste for Beckham should be hardwired into my DNA, given that he's spent most of his career playing for Manchester United, a rival team I've never had any problem despising, and confess to shouting vile abuse at during some of my weaker moments as a human being.

For those unfamiliar with the tribal nuances of English soccer, Manchester United is the equivalent of the New York Yankees — a team whose deep pockets and propensity for sucking up talent make even George Steinbrenner look positively parsimonious. They are a hard team to love unless you come from Manchester, or are one of those sports fans who always want to back a winner.

Add in the Spice Girl wife, and the absurdities of the couple's celebrity lifestyle, such as their lavish residence dubbed "Beckingham Palace" by the British tabloids, and you'd think Beckham would be about as lovable as Paris Hilton after one too many mojitos. Yet he's a curiously likeable chap — even my celebrity-immune mother thinks so.

The L.A. Galaxy isn't getting the second coming of Pele. Beckham's a very good player, but he isn't a great. He's not a human highlight reel like Michael Jordan. There were times when he wasn't even an automatic starter for the first team at Manchester United.

Yet Beckham helped his team to six Premiership Championships in a decade before his 2003 transfer to the Spanish club Real Madrid. This year, with Beckham playing some of the best soccer of his career, Real won the Spanish championship for the first time in three years. He's an excellent team player who makes those around him better, and, yes, no one can "bend it like Beckham" — the ball, that is.

A mainstay of the English national team, which he captained more than 50 times, Beckham was dropped by England's new coach after the 2006 World Cup, only promptly to be brought back to a hero's reception when England proved incapable of winning without him. One of the sub-plots of his move to the Galaxy is whether he'll be able to retain his place in the England lineup while playing in what is generally considered (sorry America) to be an inferior league.

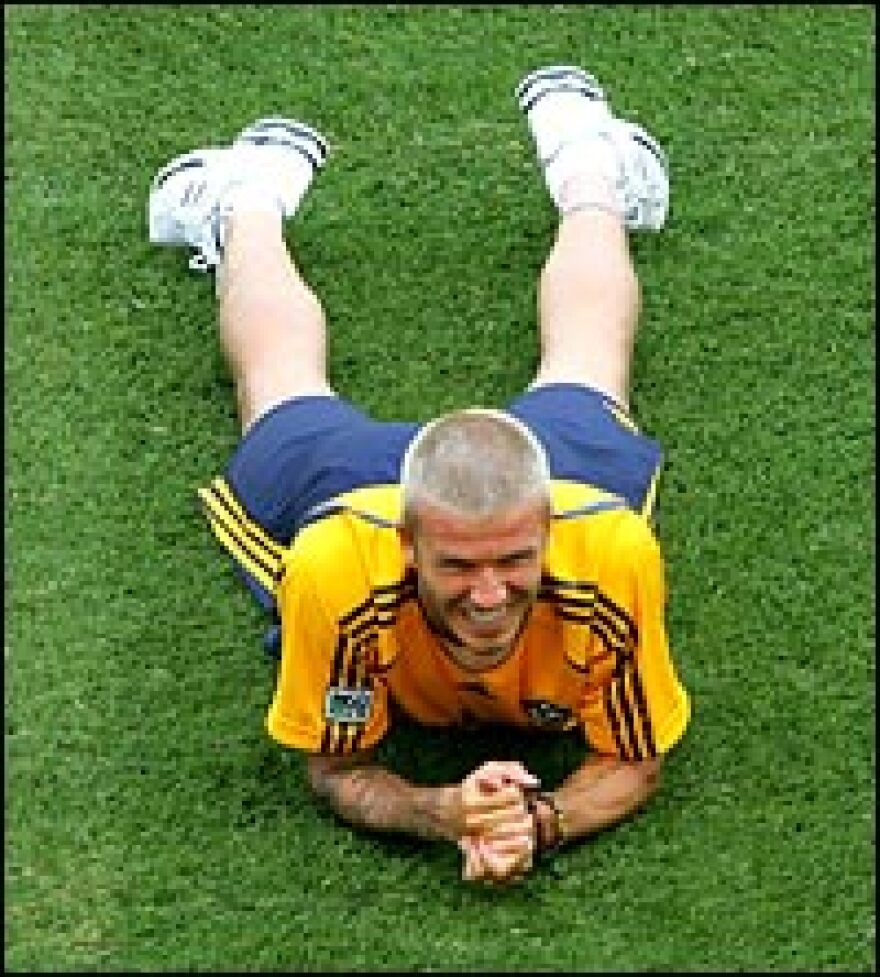

In truth, though, Beckham off the field — the global icon who graces billboards from Hollywood to Hanoi — is more interesting than Beckham the footballer. Certainly, he's photogenic and he's had some good career advice. But that doesn't fully explain the Beckham phenomenon.

Part of the man's charm, is that having sought celebrity, he seems to genuinely enjoy it, even under the rapacious glare of Britain's tabloids. In matters of class, race and gender Beckham is a uniter, not a divider — he crosses all kind of boundaries. The young Manchester United star came of age when English soccer was metamorphosing from a hooligan-riddled national embarrassment to one of the world's premier sporting leagues. Beckham has been the perfect ambassador — comfortable with himself, comfortable with others.

Born in East London, he may have married "Posh," but he's never forgotten his working-class roots. He's close to his parents. Like many contemporary sports stars, his kids' names are tattooed on his body. Unlike some, his devotion to Brooklyn, Romeo and Cruz seems to go beyond mere calligraphy — at least if one believes the many glossy spreads in celebrity magazines.

In a sport still riddled with racism and anti-Semitism, Beckham has spoken of his Jewish heritage. And then there are the famous pictures of the Superstar elegantly clad in a sarong, which launched one of the odder fashion revolutions of recent times. Until Beckham, most Englishmen would rather have their fingernails pulled under duress than be caught in a sarong. Perhaps Beckham's lasting contribution to British culture is he's helped redefine what it means to be macho. He's made it safe for a generation of British men to get manicures without being laughed out of the pub by their mates.

The future of soccer in America will be determined on the playing fields of suburbia, where legions of young players are discovering the game's democratic simplicity. Beckham isn't the savior of Major League Soccer. But even if Beckham's contract really is worth $250 million counting endorsements, my guess is that the Galaxy, American sports fans and the readers of US Weekly will all get their money's worth and more. And if a West Ham fan says that about Beckham, you can take it to the bank.

Christopher Turpin, the executive producer of All Things Considered, grew up in Essex, England. He achieved journalistic nirvana in 1994 when he was assigned to cover the World Cup competition in the United States.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDM3NjYwMjA5MDE1MjA1MzQ1NDk1N2ZmZQ004))