It wasn't as if I intentionally set out to work for one of the lowest forms of media. It just sort of happened. As a 21-year-old communications and English major, I longed to carry a business card that would label me as a high-profile reporter. I envisioned that I would be surrounded by ringing cell phones, my hair tied in a loose bun with a stylish pair of gold-rimmed glasses dangling from my lips. I wanted to be the one searching frantically for the taped interview for tomorrow's cover story. I wanted to be Katie Couric.

After all, I hadn't exactly popped out of the womb singing "Hollywood" or even had a desire to see my face on the big screen, for that matter. But somehow I ended up in Los Angeles, smack dab in the middle of the tabloids. In a city where people blend together like salt crystals in a shaker, there I was, a single speck of pepper, trying to fight my way out of the spout.

As the daughter of a minister, I was encouraged to walk the "straight and narrow path." Each generation of my family tree had produced dedicated preachers and foreign missionaries. By sprouting off in my own direction, I was determined to avoid becoming just another typical branch in my heritage.

After graduating early from Westmont College, I moved to LA to share a condominium with my sister, Heidi. Although she is only two years older, we are as opposite as siblings can be. Heidi excels in math and science, while I always rely on calculators. She has blue eyes, fair skin, and lives under a layer of SPF 35. My eyes are green, I live to surf, and I chase the sun. Heidi is sensitive and compassionate with a desire to deliver medical supplies to third-world orphans. I am raw and spontaneous and take risks as if I were indestructible. Considered "grounded and brilliant," Heidi brushes those labels aside and insists that our dissimilarities bring balance to our wobbly spirits. I think she's right. Over time, my sister and I have developed a common understanding of our roles. I will continue to live the way I want and Heidi will make sure nothing falls apart. Yet, for all her years of damage control, Heidi will never forgive herself for introducing me to her campus Web site. Using her student code, I gained access to the UCLA job board.

"Would you look at this?" I said, pointing to our computer screen.

"Globe magazine is hiring celebrity reporters. Maybe I should send in my resume."

"Maybe," Heidi suggested apprehensively, "you should think about getting your teaching credential instead."

Ignoring her concerned pleas, I spontaneously sent my resume to Globe. Later that week, I received a call to interview with the magazine, a publication I had never read or even purchased. Eight days later, I was scheduled to meet with Globe's West Coast bureau chief, Madeline Norton.

During the week prior to that fateful meeting, my family and I went on vacation to Hawaii. The first day of our holiday ended painfully with my family lying flat on the floor, charred to a crisp after naively believing that our base tans could brave the tropical rays. There we were, side by side on our bellies, looking like bright, pink sausages lined up on the rotating spit of a 7-Eleven hot dog warmer.

Our faces buried in the carpet, we were only vaguely aware of the background noise of CNN's world news coming from a television in the corner of our rented condo. Suddenly, regular programming was interrupted by a special report announcing that Princess Diana had just been involved in a serious car crash. At the time, the extent of her injuries remained unknown.

Without making the correlation between my upcoming interview and the historic events unfolding on the screen, I remained absorbed in my own burnt suffering. It was agonizing to peel away my sun-pasted bikini. "More aloe," I motioned to the lifeless bodies around me. Responding to my tormented call, my mother began rubbing the green goop on my back.

As CNN's coverage continued, one expert after another began to blame the paparazzi for the accident, naming them as the primary culprits. Breaking away from the horrific scenes in the French tunnel, live footage cut back to the CNN studio as the anchorman introduced yet another guest.

"Here, to speak on behalf of the tabloids," he was saying, "is Trenton Freeze, editor in chief of Globe magazine."

I lifted my inflamed face long enough to take notice of Mr. Freeze. It was my first introduction to the man who would later become my boss. With slightly graying hair and coaster-sized glasses, he spoke with a thick British accent.

"Oh, how splendid," I said, mimicking his English pronunciation. "It appears my future boss is defending the tabloids on the telly."

My mother stopped rubbing my back. "Marlise, please don't tell me this man runs the magazine where you'll be interviewing on Monday."

"Calm down," I said, dropping my head between my burning arms. "I don't even have the job yet."

"But how could you even think about working for those people?" my mother asked. "Princess Diana may very well be dead."

"Well," I snapped, "I didn't kill her."

And that was the end of our discussion. The next week, I stormed the doors of the great American tabloid. In retrospect, it is a wonder that the editors even granted me an interview. My journalistic background was far from comprehensive. It consisted of two summer internships at a Monterey, California, tourist publication, where I did everything from layout to writing copy and selling ads. After college graduation, I spent fourteen months working at a stock footage library in Hollywood. As a production assistant, I helped film everything from street scenes and buildings to taxis and airplanes. Production companies would order these specific stock shots to be spliced into movies and television shows. That Hollywood exposure, combined with my journalistic experience, was apparently enough to get me through the tabloid doors.

With a portfolio of my writings in hand, I entered the lobby of Globe magazine. Because of my limited background in celebrity reporting, I had little confidence I would get the job. Watching the Oscars® was about as close as I had come to the private lives of Hollywood's rich and famous. At the time, however, Globe's desperation was my ticket to employment.

I was escorted into the office of Globe's West Coast bureau chief. Noticeably absent were the customary questionnaires, clipboards, and editing exams. Our interview was brief and direct. My fate was ultimately determined by my answer to a single question:

"What would you do," Madeline asked, "if you believed that Tom Cruise was cheating on Nicole Kidman?"

At that moment, all I could think about were my sweaty palms and how they might reveal my insecurity. Phone lines on the editor's desk were lighting up like a Christmas tree at Nordstrom.

"Excuse me for a moment," she murmured, pressing her manicured nail onto a blinking light. Placing the call on hold, she ordered someone in the other room to "bring the JonBenet rewrite." I wiped my damp hands on the arm of the chair before folding them tightly in my lap.

The walls around me were studded with paparazzi photos encased in gold frames. Like trophies on display, each photograph represented another life that had been changed by a single flash and a probing lens. There they were, all those well-known images: Michael Jackson covering his burnt face, a pregnant Farrah Fawcett sweeping her garage, and a young Liz Taylor romancing in Rome. I felt as if their freeze-framed eyes were begging me to reconsider.

"Stop it," I pled silently to the desperate celebrities screaming in my head. "I'm making a decision here and I can do it without your help."

The editor slammed down the phone. "So, where were we?"

Picking up where we had left off, I blurted, "I would follow him."

The editor leaned over her desk with a look of confusion. "Excuse me?"

"Tom Cruise," I answered. "I would follow him."

Standing up, she walked toward me and extended her hand. "So, we'll be seeing you on Monday then." It was an announcement, not an invitation.

Monday? Do I have to come back for another interview or did she just offer me the job? What is the job? Can I ask her? No, Marlise, you can't ask her that. Act confident.

"You know, it's nothing official," she continued with a saccharine smile. "We'll just take it one day at a time and see how it goes. But I must admit I have a good feeling about this."

Easy, Turbo. This is going way too fast.

"Actually," I mumbled, trying to cover the damp handprints on my skirt, "could I have a little time to think it over?"

The editor seemed stunned to have a 21-year-old challenging her game. Regaining control, she slipped me her card. "You have exactly twenty-four hours."

The interview was officially over.

That evening I phoned my parents, who habitually tell me what need to hear rather than what I want to hear. "Mom, Dad, I'm becoming a tabloid journalist."

Silence.

"What do you exactly mean when you say 'tabloid journalist'?" my father asked. I told them everything I knew about the position, which was not very much. I understood their hesitation, but I was unwilling to pass up this opportunity.

"Do you really have to write for a tabloid?" my mother asked.

"What about working for CNN or National Geographic? If you take the job at Globe, you won't be climbing the corporate ladder. You'll be climbing the corporate footstool." She was probably right. After all, how could a tabloid reporter ever become a respected journalist?

By this time, the death of Princess Diana had been officially confirmed. It seemed as if the whole world were in mourning. The tabloids in general, and paparazzi in particular, were under fire for their alleged roles in her untimely death. The tragic passing of the internationally adored princess only worsened the infamous reputation of the tabloids. The timing could not have been worse for my career change from production assistant to tabloid journalist.

Consistent with my reputation for spontaneity, I picked up the phone and called Madeline. Without fully realizing where it would take me, I accepted the position as a tabloid reporter.

The transition was rough.

Day one at Globe felt like an eternity. After leaving my car in underground parking, I signed in with building security and took the elevator to the ninth floor. Walking down a long, narrow corridor, I made my way to suite 925. I knocked and waited. The heavy blue door was flung open.

Standing there was an attractive African-American woman who appeared to be in her early thirties. "You must be Marlise," she said, reaching out her hand. "I don't think we've officially met. I'm Sharmin."

"It's nice to meet you, Sharlin," I responded, giving her a firm grip.

"No," she said, letting go of my hand. Turning away, she led me into the lobby and continued. "It's Sharmin, as in, 'Don't squeeze the Charmin.'"

I smiled, wondering which had come first, the toilet paper or her birth.

Dramatically waving her arm over the couch like a game show model, she asked me to take a seat. Rather than receiving a traditional office tour or a formal introduction to the staff, I was handed a stack of magazines and told someone would be with me shortly. For the next forty-five minutes, I sat there flipping through the pages of Globe, wondering what on earth I had gotten myself into.

Fortunately that moment marked the only time I would ever sit on the "outsider couch," reserved solely for sources and the endless string of auditioning reporters. The lobby was a cold and forsaken place, with more of the intimidating paparazzi photos covering the walls. The furnishings were sparse. In addition to the uncomfortable loveseat, the room held a black slate reception desk. That desk remained empty throughout my years at Globe, during which the magazine never hired a receptionist.

Instead, those duties were performed by Sharmin, who informed everyone that she was the "senior assistant to the bureau chief." Over and over, we could hear her sexy telephone voice echoing from around the corner, "Thanks for calling Globe. This is Sharmin. How may I help you?"

Despite her claims of being overworked and underpaid, Sharmin was the office favorite. Everyone adored her, especially the FedEx man, who blushed when she dropped enticing lines like, "Do you make afterhour deliveries?" She flirted with the men and befriended the women, wrapping nearly everyone in the industry around her little finger.

Somehow, Sharmin had even convinced upper management to grant her paid vacation time for any day related to minorities: Martin Luther King Jr. Day, Slavery Abolition Day, Cinco de Mayo, Rodney King Conviction Day, and even the anniversary of Tupac Shakur's death. She loved to joke," Whose idea was it to put cotton in the top of a medicine bottle anyway? I say leave the cotton pickin' to the white man. Set my people free."

With a mastery of multitasking, Sharmin could talk on the phone, write up leads, file her nails, and play computer solitaire, all at the same time. Ultimately, my friendship with Sharmin was one of the reasons I stayed in the industry. But day one was another story. From the beginning, she had mentally written me off as "some rich white girl who won't last a week."

Almost immediately, I sensed that I was disliked by the staff. Teamwork was nonexistent, and there was little opportunity to get to know one another. We only worked together when a predecessor had failed, or, on those rare occasions when assignments required us to blend as partners.

The editors constantly reminded the reporters that they could not "afford" to have us sitting around. This seemed odd, given the fact that the publishers were selling more than two million magazines each week. Yet we all knew that any reporter who did not produce regular leads would be fired. We were set up to become competitors, not teammates. It was a dog-eat-dog world and we were the dogs. It was that simple.

Naturally these realizations only became clear to me over a period of time. From the moment Sharmin escorted me to my section, there were clues that I was entering a company of quick employee turnover. Empty desks and barren bulletin boards hinted at a staff that could never completely settle into the system. The office was surprisingly quiet. There was little movement, except for the sound of typing and the occasional ringing phone. My long-anticipated visions of a frenzied newsroom, perfumed with the smell of cigarette smoke and black coffee, would have to remain a stereotypical image inside my head.

White walls and black desks made the place look stark. In the main section, there were six desks, with three on each side of the open room, lined up one behind the other. The small tabloid family was made up of only five staff reporters, nine editors, and three assistants. Head of the LA household was the Los Angeles bureau chief, Madeline. There was very little to know about her personal life, particularly since she didn't seem to have one. Commuting three hours from Santa Barbara every day, Madeline dedicated herself to Globe as if she also lived in fear of the tabloid guillotine. She came in early and left late.

About five feet tall, she wore flat dress shoes, tan nylons, and bland skirts that hit directly below the knee on her pear-shaped body. Her auburn hair was styled in a pixie cut, but I thought she was far from the magical Tinkerbell. Although her normal practice was to stay inside her office, she occasionally paced up and down the center aisle of the open room like a flight attendant, making sure that seat belts were fastened and tray tables were in their upright position. During these periodic appearances, she sprinkled her fairy threats of, "Leads, people! Where are your leads?"

She had hired me on a risk and could have fired me on a dime. Oddly enough, I felt indebted to her for employing me without journalistic credentials, tabloid experience, or an extensive portfolio. Countless complaints bounced off the office walls, but none of them could accuse Madeline of a lack of commitment. Typically, this would be the appropriate time to say she took me under her wing and taught me everything I know about journalism. But that would not be true. In reality, Madeline pushed me off the edge of Globe and forced me to fly alone.

That first day should have given me a clue of what was to come. After sitting alone in Globe's lobby for almost an hour, I timidly walked around the corner to Sharmin's desk. "Excuse me," I said, wondering if they had forgotten about me. "Was I supposed to be meeting with someone or doing anything in particular?"

Sharmin's expression showed me that I had, in fact, been forgotten. "Oh, right," she answered. "Why don't you follow me?"

As we walked through the office, the handful of reporters did not even glance up from their desks long enough to make eye contact. No words, waves, or smiles were exchanged. Sharmin led me to an empty desk at the back of the office. She handed me a second stack of magazines, including the latest issues of Globe, National Enquirer, and Star.

"Read through these," she said. "They'll give you an idea of what we're about."

Within that first hour, I read everything Sharmin had given me from cover to cover. Naïve to the world of weekly publications, I came face to face with stories such as JonBenet Ramsey's murder, Princess Diana's death, and Kathy Lee's marriage to Frank Gifford.

At the time I had no way of knowing that the National Enquirer would soon publish a story alleging that Globe had paid $250,000 to a former flight attendant to lure Frank Gifford into a hotel room. The Enquirer further claimed that the encounter had been taped with a hidden camera. But on my first day, I knew none of that.

As a novice tabloid reporter, I had no idea what it meant to find "a source." The fact that the magazine bought stories was meaningless to me. Eager to start writing, I was desperate for some sort of direction.

"Excuse me," I said, spinning my chair toward a young, blond reporter. "Could you possibly tell me what I should be doing? It's my first day. I'm a bit clueless, to be perfectly honest."

Biting into his tuna sandwich, the reporter paused to finish his mouthful. "It's noon," he said. "You can take your lunch break if you want."

"No, I mean as far as work goes," I continued with embarrassment. "What do we all do?"

He wheeled his chair toward me and whispered. "Listen, it's only my second day at Globe. If you want to keep your job, I suggest you try to look busy." Pointing toward a rack of publications, he added, "Grab a mainstream magazine and start looking for a buried quote. Maybe you can create a story from something a celebrity said in another interview."

"Thanks," I whispered back. "By the way, I'm Marlise."

He wiped his mayonnaise-smudged mouth with the front of his sleeve. "I'm Adam, Adam Edwards, from New York."

Other than Sharmin, Adam was the only person who spoke to me all day. From time to time, Madeline would pass my desk on the way to the conference room, but she never acknowledged my existence. I was beginning to wonder if I were invisible.

At Adam's direction, I spent the next five hours flipping through the pages of Time, People, USA Today, and Elle. Although I was far removed from the world of celebrity gossip, everything seemed to be old news, even to me. One by one, the other reporters shut down their computers and left the office, calling it a day.

"It's six o'clock," Sharmin said, reaching for her purse. "You can leave now."

Fearing my days at Globe were numbered, I drove home deep in thought. When people asked me how it had gone, I had no idea how to respond. It was one of the strangest days I had ever experienced in an office.

Day two was even worse. No one spoke to me, helped me, or guided me. The only change was on my desk, which now bore two pencils and a stenographer's notepad. After skimming through twenty magazines, I compiled a list of five story ideas pertaining to everything from "Madonna's Beauty Secrets" to "Charlie's Angels, Where Are They Now?" By five o'clock, I had worked up enough courage to knock on Madeline's door.

"Yes?" she murmured without looking up from her desk.

"Sorry to bother you," I said shyly. "I came up with a few possible story ideas."

Speed-reading through my list, she handed it back without giving me any direction. "Not bad, but keep trying."

I walked out of her office feeling more defeated than encouraged. Day three was a repeat of the initial two, except for the appearance of a reporter seated in the desk beside me.

"Well hello, luv," he said brightly with a strong British accent. "No one told me we were getting a new bird in the office."

Reaching out his hand, he introduced himself as Patrick Kincaid.

"Marlise," I said, relieved to have a bit of conversation. "I didn't realize anyone sat in that desk. Do you have Mondays and Tuesdays off?"

He laughed at the absurdity of my question. "There are no days off here. I've been on assignment in Texas. Do you know how much beef they have over there? I've never seen so many fat people in my life."

He had lost me.

"I've been doing a story about Oprah supposedly destroying the beef industry," he continued. Pantomiming the headline in the air, he added, "'Farmers Rage: Oprah Ruined Our Lives!' It's a brilliant story, really. But I can't bother being tied up in here all day. Especially with that witch looking over my shoulder every five seconds. I would have left Globe long ago, but I'm signed on for a year."

Patrick tapped his pencil on the desk. "Whatever you do, never get involved in contracts. The tabs brought me over from the British papers a few months ago. Supposedly I'm a roving editor, but I don't like that title. It makes me sound like a bit of a wanker."

"Well, at least you know your job," I said, leaning over to whisper. "I have no idea what I'm doing here."

"You're not much different from the rest of us then," Patrick laughed, lifting the cover of his laptop. "See if you can get one of these beauties. Then you can actually pretend to be busy."

I glared at the enormous computer that was on my desk, similar to the one I had used in elementary school. It looked like it operated on the DOS system, controlled with turtle-slow arrow configurations rather than by a mouse.

Booting up the tank, I wondered aloud, "Do these things actually work?"

"Well, you can type on them," Patrick explained. "But you can't check the bloody football scores now, can you? "He turned his laptop screen toward me with a little victory shove to show me the sports Web page.

I was surprised to learn that most of the office computers lacked Internet access. Looking back, this made the research process of tabloid journalism that much more remarkable. Further into the job, I was told that we were expected to rely on a file room for our data gathering. Filled with newspaper clippings and magazine articles, it contained a file on nearly everyone in the entertainment industry. If the file library lacked the specific information we needed, we were to call Marsha Powell in the Florida office. She would then fact check everything from celebrity birthdates to their past flings. Marsha was amazing. She single-handedly faxed reporters all of the requested information within minutes.

Most of the time, tabloid journalists relied on sources for gathering information. At this point, I had not yet established any useful contacts. Lacking sources, I used my lunch breaks to research current celebrity Web pages from my home computer. Some time later, Globe installed dial-up Internet, which gave me an added level of job security. Oddly enough, in this office of old-school veterans, anyone who knew how to operate e-mail was considered computer savvy. In their words, the Internet was "much too technical." Apparently Patrick and I were on our own when it came to the world of Yahoo.

"So, how do you like the job so far?" he asked, looking up from his screen.

"Well, there isn't too much to like, really," I said. "To be honest, I'm a bit frustrated at the moment."

Patrick turned off his computer as if calling it a day. "Keep your chin up, luv. I reckon you'll be the star of Globe in no time."

Day three had ended without making any progress. That evening, I watched Inside Edition, Access Hollywood, Entertainment Tonight, Extra, and the E! channel, determined to get a sense of celebrity reporting. I had to get up to speed in the world of gossip. My hope was to capture a line that I could develop into a story. The following morning I typed out a list of possible ideas and placed it on Madeline's desk. Nearly an hour passed before she made any reference to my efforts.

"Marlise," she called from inside her office. "Come in here for a moment, please."

Holding my pad and pen in jotting-ready position, I practically ran to her office. Madeline began talking even before I entered the room.

"I like your enthusiasm. But you've got to think headlines. Headlines, Marlise! Like here, for example." She pointed toward my idea to interview Anthony Hopkins about his upcoming role in The Edge.

"Obviously Hopkins is not going to give us an interview, nor would we want one. Find out something else that is going on around him. I think you're headed in the right direction."

She handed me back my list and continued about her work. Although I had absolutely no idea what she was talking about, it seemed pretty clear that I dare not ask. During my lunch break, I raced home and researched The Edge on the Internet. The leading stars in the film were listed as Anthony Hopkins, Alec Baldwin, and Bart, the bear. The name of the bear's publicist and contact information were listed below the animal's film credits. Dialing the management firm, I explained that I was a reporter who was interested in interviewing the animal's owner. Viewing the exposure as harmless publicity, the bear's publicist organized a telephone interview with Bart's owner, Doug Seus, for later that afternoon.

Back at the office, I composed a series of questions similar to what one might ask an actual actor. How does the bear stay in shape? How many hours of sleep does he get? What are the bear's favorite foods? Does he have a girlfriend? Has he been to acting school? Does he ever get moody? I then called the bear's owner. Midway through my telephone conversation, Madeline walked past my desk and motioned me into her office. After I hung up the phone, I knocked on her open door and entered.

"Who were you talking to?" she asked, somewhat puzzled to see me using the phone.

"The bear," I responded. "Well, not the actual bear, but the bear's owner."

She looked annoyed." What bear?"

"You know, the bear as in the bear."

"Marlise," she said, shaking her head. "We are a tabloid magazine. We want scandal."

"Well," I nodded. "I just thought it might make an interesting lifestyle piece on the wealthiest pet in Hollywood."

It was the first time I had seen her smile in four days. "So, what did he say?"

"It turns out the bear is quite a spoiled star." I waited for visual feedback from Madeline, but she gave me nothing. "He's appeared in over twenty movies. He eats Oreos, sits at the dinner table, swims laps with his personal trainer, sleeps in his own bed, makes ten thousand dollars a day--"

She stopped me before I had a chance to continue.

"Write it up. Two pages double-spaced, twelve point, Times New Roman. Have it on my desk first thing tomorrow."

I smiled the entire way back to my desk. As a so-called celebrity writer, it was somewhat humiliating to be reporting on the beauty secrets of a grizzly, but the following day, I realized that this single story saved my job. With hardly any editorial corrections, Madeline signed off and faxed my story to Florida headquarters. The article was published as a full-page spread with my byline.

It took me only one week to adjust to tabloid lingo. "Tone down your vocabulary a bit," Madeline scolded. She claimed that my writing style sounded like it was addressed to an educated audience. She explained that I needed to target the trailer-park readers who thrive on stories like "Oprah Battles the Bulge. "Within a few days, I learned to incorporate catch phrases into my articles. Among the tabloid favorites were "hunky beau," "love nest," "tragic heartbreak," and "secret romance."

It was quite a week. Adam from New York barely made the cut. He survived only after aggressively assisting a veteran reporter on a Brady Bunch update. Unable to make the same deadline, another rookie reporter whom I never met was fired the following day. That Friday, Sharmin distributed a memo announcing staff happy hour at LA's Westwood Brewing Company.

"Remember to bring extra flow for the less fortunate," she added, holding out her hand. "I'm not too proud to beg for money."

After work, I drove to the bar where the majority of reporters were already well into their pints and cocktails. Madeline and Sharmin were there. Patrick Kincaid showed up but ignored the entire bunch in exchange for being able to watch televised sports on ESPN. Adam sat across from me, looking just as relieved as I felt to still be employed.

"Have you met the staff?" Madeline asked, pointing her wine glass toward the others around the table.

"No, just Patrick and Adam," I replied.

One by one they welcomed me to the team.

"I'm Karen," said one who looked rather pale. "I specialize in covering soap opera gossip."

Over time, I discovered that Karen was somewhat timid and introverted, most likely as a result of some chronic health issues. Then there was Pete, a 350-pound bundle of pure tabloid bliss. Digging into the nut bowl, he threw back a handful of almonds and introduced himself as "the unorganized one of the bunch."

Like Sharmin, Pete was adored by everyone. Suffering from severe narcolepsy, he was notorious for two things: falling asleep at his computer and stashing candy wrappers inside his desk. Pete's chocolate fetish was the root of all ant problems at the office. When he typed, he used an unorthodox two-finger punching method, but still managed to write as fast as the rest of us. After a year at Globe, Pete had already mastered the tabloid formulaic jargon and was viewed as the greatest wordsmith in the industry.

The rest of the LA staff was made up of a handful of freelance reporters like me. We had no binding contracts, no benefits, and no formal proof of our relationship with the tabloid. As freelancers, we received a flat day rate of $200 and knew that Globe could drop us at any moment. One such freelancer introduced herself as Ronda and appeared to be in her early fifties. Turning to the mustached gentleman by her side, she said, "This is my husband, Jacques Pierre."

"So, are you both reporters?" I asked, turning toward Jacques Pierre.

"No," Ronda answered, speaking for him. "He's a photographer."

Maybe it was the language barrier, but by the end of the evening, I realized that Ronda did all the speaking for both of them. The couple was seldom seen in the office and predominantly worked from home as dedicated freelancers. Then there was Jason, the smooth operator. He kissed the back of my hand and explained that he dealt with the dirty side of the business. Throughout the evening, he inched his chair closer and closer toward mine. Jason had a habit of winking at the end of each sentence and repeatedly suggested another toast to "new beginnings." I found him a bit creepy.

Pete leaned over and whispered, "Jason digs in celebrities' trash cans in search of anything that might lead to a story."

Nodding, I excused myself and went to the restroom to scrub my hands. Returning to the group, I asked, "So where is the rest of the staff?"

"This is it," Madeline explained. "At least on the West Coast. Most of the news comes out of our LA office even though Globe's headquarters are in Florida."

Everyone seemed much more relaxed in this setting than they had been at the office. I was stunned to learn that there were seldom more than five full-time staff reporters, plus freelancers, working from Hollywood at any time. It was amazing that these reporters could produce as much as they did each week. By the end of the evening, I began to realize that life behind the walls of Globe was not what might be expected from one of the world's most scandal-filled magazines. My fellow journalists were not evil or malicious, nor were they on a mission to destroy lives. They simply wanted to write and get paid for it.

They were an unusual bunch. Although they made a living from delving into the details of celebrities' lives, they neither asked nor shared information about their own. Sometimes they made jokes I didn't get and had sayings I didn't understand. At other times, the office was awkwardly quiet, the silence only broken by the sound of an air bubble rising to the top of the water cooler.

As far as I could tell, no one had any enemies that they knew of, until of course those cyclic days when Madeline would invite a reporter into her office and close the door. One by one we would lower our heads, sensing we were about to lose another solider from the battlefield. We came to think of the simple act of that closed door as the tabloid guillotine, ready to behead another reporter at any moment.

The industry itself was structured on a well-defined hierarchal scale. There were distinct levels of seniority on the tabloid pen. Madeline reigned somewhere on the cap while the rest of us clung to the sides of the pocket clasp for fear of sliding onto the page and smudging the ink. Above the LA bureau chief was the Florida staff. That team consisted of a cluster of executives who generally communicated through the chain of command. Never once did I meet the faces behind those ominous voices, nor did I ever visit the headquarters in Boca Raton. To this day, it remains a corporate Neverland, where people dream that someday, they too might be able to fly away from the tabloids to become respectable writers.

Our brave Peter Pan was Trenton Freeze, whose name was at the top of the masthead with the unpretentious title of editor. The man I had first encountered through CNN secretly gained the nickname of "Freezy" among the rest of the staff. Most considered him to be king of the tabloids, with a history linking him to leadership at the National Enquirer and some of England's best-known dailies. Trenton Freeze was the equivalent of our feared father, seldom pleased with the work we produced.

There were, however, a handful of memorable times that his calls were patched through to my personal line. Always notified prior to his calls, I was coached on how to respond to his comments.

"Excellent work on your latest cover story," he would say. "Keep it up." There would be an awkward silence, before a burst of "Cheerio!" would precede the final hang up.

Sandwiched between Freezy and Madeline was the Florida-based managing editor, Cathy Tidwell. Again, I had very little direct contact with Cathy, although it was significantly more than I had with Trenton Freeze. Occasionally I would receive one of her "not too bad" phone calls, accompanied by a pep talk to keep me going in the game. I never met Cathy or saw a photograph of her.

I constantly felt as if I had fooled everyone, successfully turning out stories with circumstantial luck rather than skill. My fear of the tabloid guillotine kept me furiously typing away. The turnover among reporters was staggering. Some entered the doors only as hopeful prospects. Others were viewed as potential contributors hired to help the magazine grow. As one of the few who had survived the critical first week at Globe, I was granted access to the secret vault of tabloid journalism.

Each day, I was handed more responsibility and given more insider tips. The fact that information was being revealed gradually seemed to cut down on the overall shock value of the industry's tactics. My job was saved by a series of column fillers, on everyone from Roman Polanski to Alyssa Milano. Column fillers were short, three-inch reports based on longer articles that had appeared in other periodicals.

By the close of the second week, I had been given a proper tour of the file room. I had also been introduced to Globe's research tools and data banks, such as Faces of the Nation. I was taught how to "run faces" by plugging in celebrities' Social Security numbers to access credit reports, former addresses, and lists of phone numbers of their neighbors and relatives. The starting point for all data gathering was getting the correct Social Security numbers for celebrities. All it took for reporters was a written request to Cathy Tidwell at Globe's Florida office.

We were never told how she obtained those numbers and, at the time, I was too naïve to ask. Rumor had it that Globe paid $150 for each Social Security number. The identity of that source was top secret and we never learned how Cathy worked her magic.

In time, the other reporters started to accept me as a colleague. They began to casually drop phrases that were common to tabloid insiders. These included terms such as "pulling numbers" and "running plates." When throwing a term my way, reporters were always careful to protect the secrets behind their surreptitious tactics. With the assistance of paid sources at various phone companies, Globe could pull numbers. It was then a routine matter of using celebrity phone bills and viewing the numbers they had been calling to gain insight into their private lives. "Running plates" meant contacting the Department of Motor Vehicles to determine car ownership and driving records. Eventually I was asked to perform the dreaded "door-stepping," which involved showing up unannounced on the front steps of celebrities' homes.

There were other commonly used phrases flying around the office, such as "leads" and "cold calls." The latter term referred to unsolicited tips from unconnected sources who would spontaneously call Globe. All of this information would appear on the source sheet that the editors required for every article. These sheets, seen only by editors and Globe's legal department, documented the actual names of informants who might appear in articles as "an insider" or "a pal." The source sheets were faxed to Florida separately from the related article in order to protect the identity of our sources.

As the newcomer on board, I envied the bulging Rolodex of my coworkers. They regularly turned in leads from their roster of paid contacts. Lacking sources, I lacked stories. Hungry for another byline, I asked Sharmin to patch through any new call-ins to my line.

"I'm supposed to pass them out equally," she replied. "But, considering you're new, I guess I'll make an exception." Smiling, she added, "By the way, bribes are accepted."

Flipping through a stack of new magazines, I anxiously waited for the phone to ring. Globe's phones had remained eerily silent due to increased suspicion of the tabloid's following the recent death of Princess Diana. The only exception was the occasional angry call from someone whose loathing of the tabloids had intensified over the past weeks.

Unfazed, Sharmin would reply to those callers with a polite, "Well, thank you for those kind words. I'll be sure to pass on your message."

Between the dual curse of silent phones and my lack of sources, I feared that I was about to lose my job. With mortgage payments to be made, I dreaded the possibility of being unemployed. Fortunately, a lead sheet from Madeline was waiting on my desk the following morning. Lead sheets were single pages that listed story ideas in the form of potential headlines. They could either be submitted for approval from reporters to editors or could be assigned by the editorial staff. This one read, "Patsy Ramsey auctions off JonBenet's pageant dresses." Across the lead sheet Madeline had written, "Check it out."

Madeline suggested I start by calling Christie's auction house. Lacking guidance on how to proceed, I independently decided to play the role of an interested shopper.

"I would like to buy all of JonBenet's dresses and donate them to charity," I said, creating my first fake identity.

Grudgingly checking the system, the woman on the line informed me that the dresses of a murdered child would probably never be auctioned at Christie's. It had seemed a bit odd to be inquiring about such a lead. But then again, almost anything was possible at Globe. Although that lead sheet turned out to be a false tip, it introduced me to the world of phone scams.

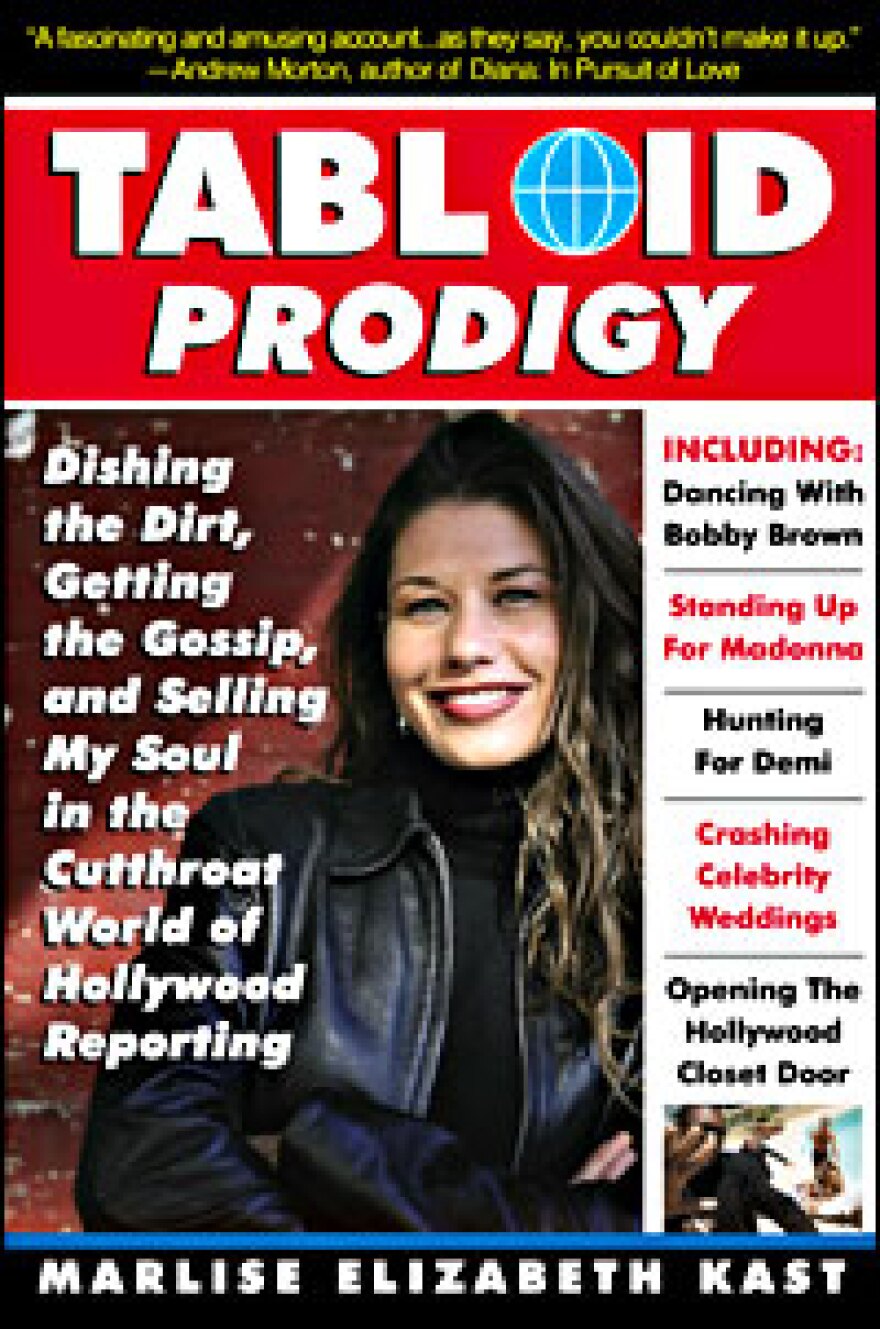

Excerpted from Tabloid Prodigy by Marlise Kast, with the permission of Running Press, 2007.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDM3NjYwMjA5MDE1MjA1MzQ1NDk1N2ZmZQ004))