Introduction

Down the dusty roads of Xi'an the motor scooters zoom, weaving around potholes and rickety bicycles, bip-bip-bipping their horns as they circle the city's 16th-century bell tower. Xi'an, pronounced Shee-ahn, is one of China's oldest cities, settled by man since prehistoric times. From 221 B.C. to 907 A.D., Xi'an served on and off as the capital of the vast Chinese empire. The famed Silk Road trade route that linked the Far East to Europe started there in the second century B.C. and turned the city, then known as Chang'an, into a throbbing metropolis of nearly two million and an epicenter for culture and politics. Painting, poetry, dance and music thrived in Xi'an, and l'art de vivre-the refined art of living-was an essential component of everyday existance. Xi'an was so beautiful, with its elaborate Buddhist temples, mosques, bustling souks and eighth-century walled imperial city that Japan's emperors used it as a model for their imperial capitals of Kyoto and Nara. It was said that Xi'an was as cosmopolitan and influential as Baghdad, Constantinople and Rome. Many considered it the greatest city in the world.

It is hard to imagine today. With a population of 8 million, Xi'an is a small city by Chinese standards, compared to Shanghai (17.8 million), Beijing (15 million) and Chongqing (12 million). Unlike Beijing and Shanghai, which, thanks to China's market reforms, have become vibrant international capitals, Xi'an suffers from the blight of Communism. The people, many dressed in faded Mao suits, seem downtrodden. Nothing has been painted in decades, scooters are held together with string, tape and hope, and everything is covered in dust and soot. The new wealth of China has not trickled down to Xi'an-at least not yet. It has some local industry-cotton textiles, chemicals and high tech-but its most important business is tourism. Half an hour away by car is the site of the Terracotta Warriors, the 8,000 life-size soldiers and horses that were buried in the tomb of Shi huangdi (259-210 B.C.), the first Emperor of Qin [or China], for more than 2,000 years and discovered in 1974 by a farmer digging a well. Each year, more than 20 million tourists-primarily Chinese-travel to Xi'an to see the warriors, making the site one of the country's most popular tourist destinations.

In April 2004, my husband and I traveled to China for the first time. I was there to cover the opening of Giorgio Armani's new retail complex on The Bund in Shanghai. Afterward, we went to Xi'an to see the Terracotta Warriors. We arrived in the spanking new airport on the outskirts of the city and took a beat-up cab down the factory-lined highway and tenement-lined streets to the historic center. We checked into the Hyatt Regency, one of the two "Western" business hotels at the time, and as we stood there in the polished marble lobby and plant-filled atrium, I remembered that the word "Xi'an" means "Western peace": the Hyatt seemed transplanted directly from any American urban center.

On the way to breakfast the first morning, we came across a couple of Chinese vendors selling clothes in a small conference room on the mezzanine. Not just any clothes: spread out across a half dozen folding tables were Gucci and Versace men's loafers, Givenchy men's shirts and socks, Versace sweaters, Calvin Klein underwear, Gucci sweaters with tags in them that read "Designed in Italy," and hanging on a garment rack in the corner, a couple of Burberry men's trench coats. Some of the items were obviously fake-some of the Versace shirts were labeled "Verla" in the same font-and I knew that Chinese factories turned out counterfeit goods of every sort. But some looked suspiciously authentic. I picked up the Gucci loafers. They were made of good quality leather, well stitched, with a slight mod design to them, just like the shoes you find in Gucci stores on Rodeo Drive or Madison Avenue. My husband tried on one of the alleged Burberry trenches. It, too, was well made and with all the Burberry details just right. We asked the price. No one in the room spoke English, but a thin twenty-something Chinese girl pulled out a calculator and tapped out the price: $120 U.S. My husband said he'd think about it. We stopped by the concierge desk to ask about the provenance of the goods. Most were legitimate, the concierge told us, and had slight defects, were from an overrun or simply didn't fit into the shipping container.

The next morning we went by the room to buy the trench. The entire operation had disappeared.

What, I wondered, was this all about?

* * * * *

The "Luxury Goods Industry" as it is known today is a $157 billion business that produces and sells clothes, leather goods, shoes, silks scarves and neckties, watches, jewelry, perfume and cosmetics that convey status and a pampered life-a luxurious life. Thirty-five major brands control 60 percent of the business, and dozens of smaller companies account for the rest. The top six brands-Louis Vuitton, Gucci, Prada, Giorgio Armani, Hermès, Chanel-have revenues in excess of $1 billion. Most luxury goods companies that we know today were started a century or more ago as simple one-man or one-woman shops that sold beautifully hand-crafted pieces. Today, those companies still carry the founders' names but are, for the most part, owned and run by tycoons who in the last two decades have turned them into multi-billion dollar corporations and omnipresent global brands. They cluster their stores on main city avenues, in airports, in outlet malls. Their advertising fill magazines and blanket billboards. Their primary customers are upper-income women between 30 and 50 years old. In Asia, the customer base veers younger, starting at 25.

Walk up to a luxury brand store and a dark-suited man with a listening device tucked in his ear will silently pull open the heavy glass door. Inside there is a hush as slim, demurely-dressed sales assistants await you in a posh minimalist space in neutral tones with chrome accents. The first thing you'll encounter are shelves full of the brand's latest fashion handbags as well as its classic designs, displayed like sculptures, each lighted with its own tiny spotlight. Glass cases are filled with monogram-covered wallets, billfolds and business card holders: the lower-priced, entry-level items aimed at aspirational middle market customers. Chances are the slim assistants will make the sale right there in the very first room. Through calculated marketing strategies and with the support of fashion magazines, luxury companies in the last ten years have created the phenomenon of the handbag of the season-the must-have around the world that will catapult sales and stock prices. Louis Vuitton's sales of Japanese artist Takashi Murakami-designed smiling cherry purses were almost single-handedly responsible for double-digit growth for Louis Vuitton in the first quarter of 2005. The average mark-up on a handbag is ten to twelve times production cost. At Vuitton, it's up to thirteen times. And Vuitton prices are never marked down.

Many luxury stores end right there: handbags and accessories. If it is a "flagship," the industry word for a store that carries the complete range of products, then there will be a gleaming counter offering perfume and cosmetics. Perfume has, for more than 70 years, served as an introduction to a luxury brand. It has allowed folks who couldn't afford the more expensive things in the shop to own a small piece of the brand's dream. It also provides luxury brands with substantial profits. Cosmetics serve the same purpose, but like handbags, are more showy: pulling a Chanel lipstick from a handbag gives the instant impression of wealth and savoir-faire.

In the next room-often upstairs or down in a converted basement-you'll find a small selection of ready-to-wear clothes and shoes. Back in the old days, when luxury was still an intimate, elegant business for an elite clientele, shopping for clothes, be it couture or ready-to-wear, was a pleasurable affair. You chose what you liked, often during a fashion show or a personal viewing, retired to a spacious, comfortable dressing room, tried them on leisurely and had the seamstress on hand to do whatever retouching was necessary. Couture and high-end department store saleswomen were counselors and confidants. They knew who was wearing what to which event and they knew what suited you and they advised you accordingly. Today, by contrast, shopping for luxury-brand clothing is an exercise in patience. Usually there are only a few pieces of clothing and only in the smallest sizes. This is where the slim sales assistants come in: they scurry into the back storeroom for 10, 15, 20 minutes to find your size, or perhaps another style that isn't on the floor, or even a dress that no one else has seen. If it doesn't please you, they scurry off again for another 10 or 20 minutes. And so on. This, in the minds of luxury executives, is attentive, specialized service.

Whatever the purchase, you'll walk out with a rope-handled paper bag in the brand's signature color and with the brand's name emblazoned on the side. The product will be wrapped in tissue paper and, if it's a handbag, wallet or other leather goods item, stuffed into a soft felt pouch, also in the brand's signature color.

And what will you have gotten?

* * * * *

The way we dress reflects not only our personality but also our economic, political and social standing and our self-worth. Luxury adornment has always been at the top of the pyramid, setting apart the haves from the have-nots. Its defining elements-silk, gold and silver, precious and semi-precious stones, fur-have been culturally recognized and sought after for millennia. In prehistory, a man set himself apart by decorating his furs with bits of bone and feathers. The Chinese enriched their appearance with silk embroidery as long as 12,000 years ago, as did the Persians and the Egyptians in the second century B.C.

The display of luxury signified one's power and achievements and brought on both scorn and envy. "'Is it a waste or not?' was argued as far back as 700 B.C.," Kenneth Lapatin, an antiquities curator at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Malibu, California, told me. The Etruscans wore gold and imported amber from the Baltics and had beautiful engraved gemstones like jasper and carnelian. But it was this love of luxury that led to their downfall, according to social conservatives of the era.

The Greek aristocrats, Lapatin explained, "were flashy. They'd wear their gold and their fancy clothing out and would be aped by the masses." This drove the rich to live more opulently, simply "to stand out" from the ordinary folk. Rulers passed sumptuary laws: social restrictions that dictated what you could display in terms of wealth-usually clothing, jewelry and other luxury items-and prevented commoners from imitating nobles and reigned in conspicuous consumption. "In some places, if you brought gold and jewelry to a sanctuary, you had to leave it as an offering," Lapatin said. "You dedicated your luxury to the Gods and often indicated your name through an inscription or label. And when people would go into the temple and see it, they would say, 'What good taste and generosity he has.'" Faking luxury was considered the ultimate disgrace. According to one ancient tradition, Pheidis offered to build the Athena statue in the Parthenon in Athens out of cheap materials-gold-gilded marble-but the proposal was vetoed by the assembly. "Shame! Shame!" its members cried and insisted on gold and ivory. "They didn't want to save their money," Lapatin said. "They wanted to show it off."

It was during the reign of the Bourbons and the Bonapartes in France that luxury as we know it today was born. Many of the luxury brands we patronize, such as Louis Vuitton, Hermès and Cartier, were founded in the 18th and 19th century by humble artisans who created the most beautiful wares imaginable for the royal court. With the fall of monarchy and the rise of industrial fortunes in the late 19th century, luxury became the domain of old-moneyed European aristocrats and elite American families such as the Vanderbilts, the Astors and the Whitneys who moved in closed social circles. Luxury wasn't simply a product. It denoted a history of tradition, superior quality, and often a pampered buying experience. Luxury was a natural and expected element of upper class life, like belonging to the right clubs or having the right surname. And it was produced in small quantities-often made to order-for an extremely limited and truly elite clientele. As Diana Vreeland noted in her memoirs, "D.V.", "Very few people had ever breathed the pantry air of a house of a woman who wore the kind of dress Vogue used to show when I was young."

When Christian Dior, considered by many to be the father of modern fashion, was interviewed by Time magazine in 1957, he pondered the importance of luxury in contemporary society. "I'm no philosopher," he said, "but it seems to me that women-and men too-instinctively yearn to exhibit themselves. In this machine age, which esteems convention and uniformity, fashion is the ultimate refuge of the human, the personal and the inimitable. Even the most outrageous innovations should be welcomed, if only because they shield us against the shabby and the humdrum. Of course fashion is a transient, egotistical indulgence, yet in an era as somber as ours, luxury must be defended centimeter by centimeter."

Dior believed that Europe was still the epicenter of luxury creation and production because of its steady stream of megalomaniacal kings and popes who, over the centuries, commissioned the construction of sumptuous palaces and cathedrals. "[We] inherited a tradition of craftsmanship rooted in the anonymous artisans who...expressed their genius in chiseled stone gargoyles and cherubs," he said. "Their descendents-skilled automobile mechanics, cabinet makers, masons, plumbers, handymen-are proud of their métiers. They feel humiliated if they've done a shoddy job. Similarly, my tailors, seamstresses constantly strive for perfection."

And there luxury stayed, a domain of the wealthy and the famous that the hoi polloi dared not enter, until the Youthquake of the 1960s. The political revolutions throughout the Western world at that time pulled down social barriers, including those that separated the rich from the rest. Luxury went out of fashion, and it stayed out of fashion until a new and financially powerful demographic-the unmarried female executive-emerged in the 1980s. The American meritocracy came into full bloom. Anyone and everyone could move up the economic and social ladder and indulge in the trappings of luxury that came with this new-found success. Since 1970, real household income in America has risen by 30 percent; one-fourth of American households have an annual income of more than $75,000. By 2005, four million American households had a net worth of more than $1 million. Both men and women have put off getting married until later in life, freeing them to spend more on themselves. The average American consumer is also far more educated and well-traveled than a generation ago and has developed a taste for the finer things in life.

Corporate tycoons and financiers saw the potential. They bought-or sometimes seized-luxury companies from their elderly founders or their incompetent heirs, turned the houses into brands, and homogenized everything: the stores, the uniforms, the products, everything down to the coffee cups in the meetings. Then they turned their sites on a new target audience: the middle market, that broad socioeconomic demographic that includes everyone from teachers and sales executives to high-tech entrepreneurs, McMansion suburbanites, the 'ghetto fabulous,' even the criminally wealthy. The idea, luxury executives explained, to "democratize" luxury, to make luxury "accessible." It all sounded so noble. Heck, it sounded almost Communist. But it wasn't. It was as capitalist as could be: the goal, plain and simple, was to make as much money as heavenly possible. And it worked. In the past two decades, luxury executives have become among the wealthiest people on the planet.

To realize this "democratization," the tycoons launched a two-pronged attack. First they hyped their brands mercilessly. They trumpeted the brand's historical legacy and the tradition of handcraftsmanship to give the products an air of luxury legitimacy. They encouraged their designers to stage extravagant or provocative fashion shows-at a million dollars a pop-to drum up controversy and make headlines. They spent billions of dollars on deliberately shocking advertising campaigns?Dior's grease-smudged lesbian ads to sell purses, Saint Laurent's full-frontal male nudity shot to sell perfume?that made their brands as recognizable and common as Nike and Ford. They dressed celebrities, who in return told every reporter lining the red carpet which brand provided their gown, jewels, handbag, tuxedo and shoes. They began to sponsor high profile sporting and entertainment events such as Louis Vuitton at the America's Cup and Chopard at the Cannes Film Festival. The message was clear: Buy our brand and you will live a luxury life too.

Then they made their products more available, economically and physically. They introduced fashionable lower-priced accessories that most anyone could afford. They expanded their retail reach from the original polished oak-paneled family shop and a few overseas franchises to a vast global network, rolling out thousands of stores that are as ubiquitous and approachable as Benetton or Gap. They opened outlets to sell leftovers at bargain prices, launched e-commerce sites on the Internet, and ramped up their share of duty-free retailing. In 2005, travelers purchase $9.7 billion worth of luxury goods each year, accounting for one-third of all global travel retail sales. And travel experts say it's only going to increase.

Luxury brands funded this expansion by listing their companies on the world's stock exchanges. Going public brings many advantages to luxury companies: it raises capital, elevates the brand's status, creates management incentive such as stock options, and makes the company more transparent, thus attracting a higher caliber of executive management. But it also makes brands beholden to stockholders who demand increases in profits every three months. "Going public does force you to change the way you do business," former Gucci designer Tom Ford told me. "It forces you to be aware of how you are spending and where it's going, to make some short term decisions because that's what shareholders respond to, and to juggle the long term benefits with the short term." To meet those profit forecasts, the luxury brands have cut corners. They use inferior materials and many have quietly outsourced production to developing nations. Most have replaced individual handcraftsmanship with assembly line production, mostly on machines. Simultaneously, most luxury brands have raised their prices exponentially, and many justify the move by falsely claiming that their goods are made in Western Europe where labor is vastly more expensive. To further pump up their numbers, luxury brands have introduced cheaply-made, lower-priced accessories such as logo-covered T-shirts, nylon toiletry cases and denim handbags and expanded their range of perfume and cosmetics, all of which bring in substantial profits when sold in great volume. The average consumer certainly can't afford a $200,000 made-to-order couture gown, but she can drop $25 on lipstick or $65 for a bottle of Eau de Parfum spray to have a piece of the luxury dream.

All this hype and marketing of dreams made luxury brands wildly successful and their shareholders extremely happy. In their best year-1999-luxury indices rose a remarkable 144 percent, according to Bear Stearns. And analysts predict that luxury sales will soon surpass those record pre-Sept. 11 levels. There have never been so many wealthy in the world. In 2005, there were 8.3 million millionaires-an increase of 7.3 percent in a year-who possess $30.8 trillion in assets, according to the World Wealth Report. The Swiss bank UBS's wealth-management division had an influx of $76 billion in new money in 2005, an increase of 57 percent in one year. NetJets, the private jet share company, saw a business increase of 1,000 percent from 2001 to 2006. The private security firm Kroll reported that its business of clients with $500 million in assets increased 67 percent two years. And the World Wealth Report added that there has been a rise in "middle market millionaires" with assets of $5 million to $30 million.

But for some on the wrong side of this growth, those dreams have turned into the darkest of nightmares. Luxury brands are among the most counterfeited products today-the World Customs Organization states that the fashion industry loses up to $9.7 billion (7.5 billion Euros) per year to counterfeiting-and most profits fund illicit activities such as drug trafficking, human trafficking and terrorism. Luxury incites other illegal activities too. Japanese girls work as prostitutes in order to buy luxury brand handbags. Chinese "hostesses" accept shopping visits with their clients at luxury brand stores, which stay open until midnight, as payment for services rendered. The next morning, the hostess will return the purchase for cash, less a ten percent "transaction fee," thus inflating luxury brands' sales figures in China and washing away any illegal cash transactions between the woman and her client. A true story, told to me over a summer lunch on the French Riviera in 2004: A rich, hip New York banker met a pretty Russian girl in the Hotel Byblos' bar in Saint-Tropez late one night and took her home with him. The next morning, she told him pointedly: "I could really use a new pair of Gucci shoes." He understood immediately that she was a working girl and took out his wallet. "No," she said, "Gucci shoes." And to the store they went.

The tycoons' marketing scheme worked. Today, luxury is indeed democratic: it's available to anyone, anywhere, at any price point. In 2004, Japanese consumers accounted for 41 percent of luxury sales, Americans 17 percent, and Europeans 16 percent. Expansion continues in India, Russia, Dubai, and of course, China, luxury's new Golden El Dorado. While parts of China like Xi'an are still dusty and blighted, a new big-spending class is emerging at warp speed. When I visited the country in the spring of 2004, China was considered an investment for the future. By December 2005, it accounted for 12 percent of luxury sales and this figure was expected to grow exponentially. Luxury brands are opening stores not only in Beijing and Shanghai but in rapid growing second- and third-tier cities such as Hungzhou, Chongquing and even Xi'an. By 2011, China is expected to be the world's most important luxury market.

And luxury's barons have reaped the wealth. Bernard Arnault, chairman and CEO of the Paris-based luxury brand group Moët Hennessey Louis Vuitton-LMVH is the most successful of them all. In 2006, Forbes named him the seventh richest man in the world, with a net worth of more than $21 billion. His shareholders aren't doing badly either. When Arnault took over LVMH in 1990, it had sales of four billion French francs (610 million Euros) with an operating profit margin of 38 percent. In 2005, it recorded $17.32 billion (13.91 billion Euros) in sales and an operating profit margin of TK. "What I like is the idea of transforming creativity into profitability," Arnault once said. "It's what I like the most."

The luxury industry has changed the way people dress. It has realigned our economic class system. It has changed the way we interact with others. It has become part of our social fabric. To achieve this, it has sacrificed its integrity, undermined its products, tarnished its history and hoodwinked its consumers. In order to make luxury "accessible," tycoons have stripped away all that has made it special.

Luxury has lost its luster.

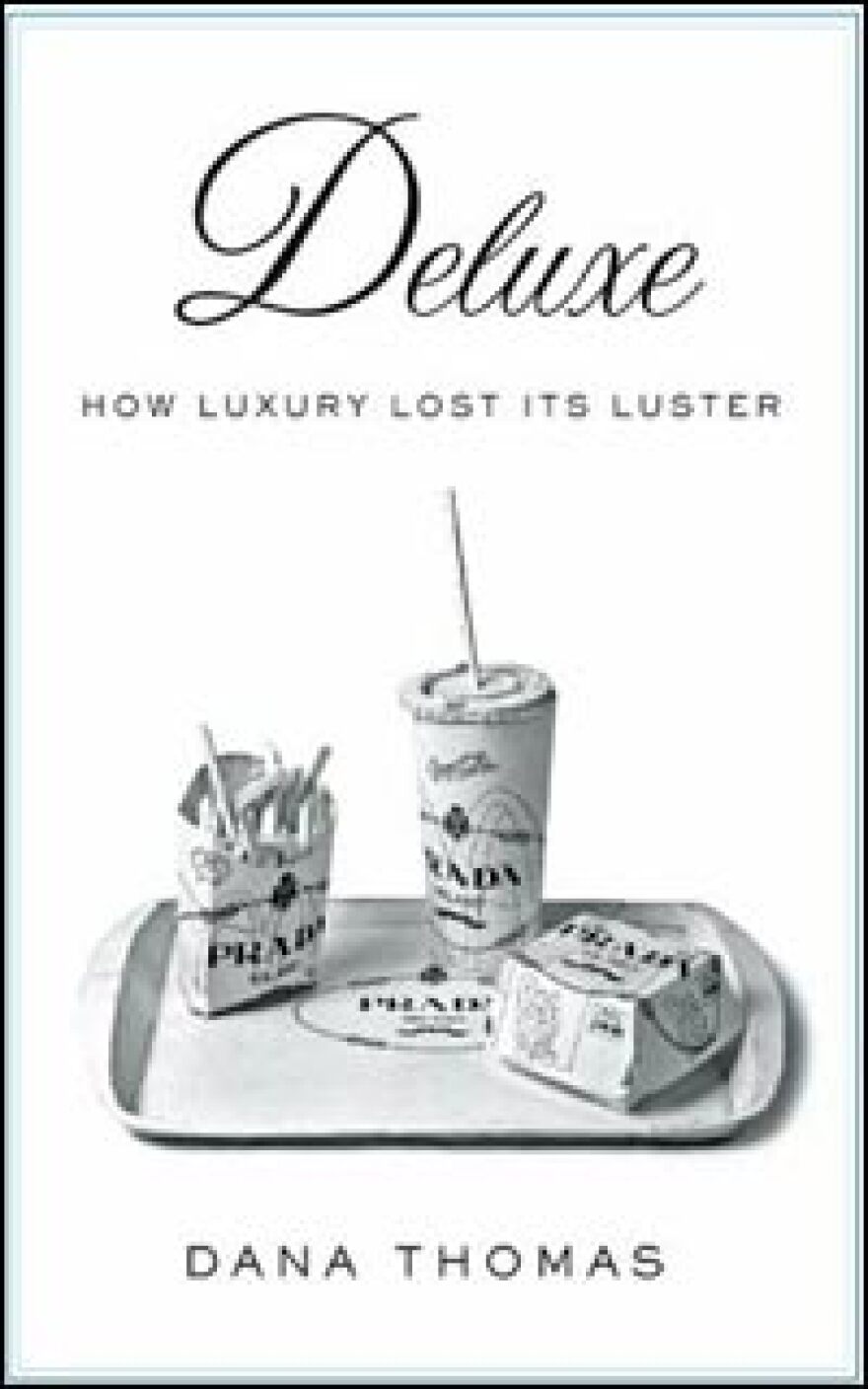

Excerpted from Deluxe: How Luxury Lost its Luster Copyright 2007 by Dana Thomas.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDM3NjYwMjA5MDE1MjA1MzQ1NDk1N2ZmZQ004))