Chapter 14 Challenges

These Iraqi detainee patients may not be what you would expect, and our interactions may not be what you would expect, either. This was a war experience, but a human experience as well. And as Indira Gandhi once said, "You cannot shake hands with a clenched fist."

The biggest challenge in caring for our patients was that the Iraqi detainees were on one side of the curtain dividing our hospital ward and our own soldiers were on the other. The enemy — maybe that detainee — put our men and women in the hospital. How could we set that aside and care for the enemy with the same diligence as we did our own men? And our soldiers had to accept that we must give the same level of care to the Iraqis as we give to them.

We didn't always have enough supplies for everyone. Should we exhaust our stores of blood and medications on the detainee patients, knowing that our own soldiers and Marines could be brought in at any time and need those supplies to stay alive?

I had not wanted to know anything personal about our detainee patients. It is against the Geneva Convention to ask a detainee personal questions, and a detainee might object if I asked too much. But that view changed for me early on, with a young Iraqi soldier who would not allow us to cut his hair. It was black, long and wavy, and really quite beautiful. He combed it in a western way, but he didn't want to look like a westerner. We teased him about his hair.

Through an interpreter, I told him the biblical story of Samson. I explained how Samson's hair gave him his strength and how Delilah, the Philistine woman, seduced him and betrayed his secret to his enemies. Samson was shorn, captured, blinded, and imprisoned. But after his hair grew out, when he was called to put on a show for the rulers, he stood between the pillars of the temple, pushed them apart, and brought down the temple, killing all the people who were in it, including himself.

He and the other detainees liked the story, and from then on that patient's name was Samson. He enjoyed being called Samson. He was so handsome that we told him he could have been pictured in GQ.

Later one day I asked him if he had a wife.

"Yes."

"Do you have children?"

"Two girls."

"Do you work?" I asked.

"Yes. I am an engineer in auto mechanics."

"Do you work every day?"

"Yes."

I was quite sure I knew the answer to this question, but I asked it anyway. "Does your wife work?"

"No."

"Do you help care for the children?"

"No. My wife takes care of the children. I play with them."

I was even more sure I knew the answer to this one, but I simply had to ask, if only to tease him. "If one needs a diaper changed, would you change it?"

Emphatically: "Never."

I told him that in the United States, men take an active part in caring for children. He said, laughing incredulously, that he would never do that. "I don't change diapers."

I said, in my best chiding, motherly tone, "You are going to go home and change diapers some day, okay?"

He knew he was good looking, and he knew we all thought he was good looking, and he was determined to hang onto his hair. Some of the soldiers and Marines thought it was sort of cool. Samson fell between conservative and fundamentalist. He would have fought to stick to some of the things he believed.

Journal entry, May 20, 2004:

I like this set of prisoners — we laugh, sing, wheelchair races. The MPs showed them the movie "Jackass!" Oh, great! Just what we want them to see — America at its dumbest. I like the MPs. I try to do any teaching I can. Am trying to do a pain management class. Help interpreters with medical words.

Most of the detainees were farmers, people from villages, and men working in Baghdad. Some had connections to the United States. One was married to an Iraqi from Detroit. She was in Iraq now, and he had never been to the States, so I think theirs was an arranged marriage. Another detainee patient had a brother who sold cars in Dallas. Others had never seen an American.

Our interpreters taught us about the differences among Iraqis from different ethnic groups or religious sects. Some of our patients were more conservative, and some, like those from urban Baghdad, were more secular. Almost everyone had dark hair and piercingly dark eyes — but we also had an albino Iraqi patient. Most of the men had mustaches; the more conservative Iraqis had full beards. The Kurdish were usually darker skinned.

In Iraqi culture, it is expected that women will wait on men and follow their orders, and some of the patients could get a little demanding. If a patient brusquely ordered a nurse to give him something to drink, a male soldier sternly told him, "Don't speak to her that way. These women are not servants. They are here to take care of you. If you can reach something, then get it yourself. Or you can drink when we pass out water or juice."

Sometimes I think they just forgot our roles, and we allowed ourselves to do the extra things they expected. Other times we had to remind them. When you see each other all day, every day, lines can blur. Then a patient might say, "Madam, I am very sorry if I offended you."

Many of the older patients spoke British English. They had studied at universities in the Middle East during a time when more English was used, and they had more exposure to the West. A couple of these were Iraqi patients identified as Al-Qaida who refused to use the translators. According to the translators, they were Jordanian or Saudi, but they wouldn't speak Arabic because the translators would then know where they were from. The translators sometimes had difficulty understanding the southern accents of a couple of our soldiers from Mississippi, and we teased about it: "Those Al-Qaida guys speak better English than you do."

We were careful not to talk casually among ourselves within hearing of any detainee. Some had tattoos on their arms that signified they were with a certain group or gang, according to our translators. The high-value detainees had to be separated from other patients and were not allowed to speak to each other. Occasionally, a detainee would be shunned by all the others, and we never really knew why. We speculated that these were the bad guys.

One of them was my patient. He was shot to pieces, but he was going to live. He said he had been to the East Coast in the United States, but he never gave anyone any specifics. He was extremely polite. He would say, "Madam, please, if it doesn't bother you too much. I don't want to disturb you, but if you have time could you turn me now?" Or, "Madam, what time is it?" Or, "Madam, do you think I am getting better?"

My gut told me to be particularly cautious and to observe him closely. I felt he wanted to be casual and kind — break down the defenses of someone like me — so he could ask questions and get answers about what was going to happen next. I heard rumors about his identity that made me even more cautious. The CIA was very interested in him.

A ward sergeant had put a sign over his bed: "High Value Detainee." I pulled it down because a clause in the Geneva Convention forbids making a patient's special status evident. We had to know, for ourselves, but if someone in authority walked through, he or she would have to see that all patients were treated the same. We followed the guidelines, placing him closest to the MPs and farthest from the desk. That patient was still there when I left. He had become more and more withdrawn.

I cared for two retired generals from Saddam's army, perhaps detained because they had information gained before they retired. They were a direct contrast to each other.

The first was a retired general in his fifties who had lost both legs above the knee in Desert Storm, the 1991 Gulf War. His fresh injuries were minimal, and he would ordinarily have been cared for in the tent prison camp. However, because of his handicap, it had become too difficult to manage even minimal cares in the tent camp. He became a patient on our ward.

This man was relaxed and rather nondemanding. His cot was in the middle of the ward, and he seemed to command the respect of the younger men. I believe that respect came mostly from his age and his status; otherwise, they did not seem to like him much.

The general was not well liked by the translators, either. They avoided him as much as possible. One translator said, more than once, "He is not a good man." When we asked why, he wouldn't tell us. He would only say, "I do not like to talk to him."

At times, the general had a good sense of humor and looked for a laugh along with the rest of us. Yet, at other times, he seemed to incite unrest in the ward. He spoke out against the war and got the other patients to talk among themselves until they had to be reminded of the rules.

When I saw other patients engage in conversation with the general, it looked to me as if they spoke only out of respect for his status and were doing so very cautiously, as if they needed to be careful not to get into trouble. Yet the general with no legs continued to command an audience as he sat like a round little Buddha on his bed.

The second retired general was probably in his sixties. The story was that he and his sons owned a tire business in Baghdad where they did a fairly good trade. Iraqi soldiers had brought in all the men in his family, perhaps because one of them had gotten into something suspicious. The general had a gunshot wound to his lower back. We weren't told how he got shot, and I never learned what happened to his sons.

The general looked distinguished, and it seemed like he was accustomed to a good lifestyle — well groomed, non-callused hands, genteel manners. He seemed humiliated to be in a ward wearing paper shorts and a top. He was stoic when dressings were changed, although I knew the exit wound on his back was painful. He asked for pain medication periodically. He spent most of his time on that ward just lying on his side, not communicating with others.

When I made my patient rounds, I asked him how he was doing, and he responded in English, "Okay." I would tell him that his wound was healing, and he nodded, but he didn't respond beyond that. Sometimes he appeared to be frightened. Otherwise, he seemed distant — depressed or worried.

I suspected he spoke and understood English, but he spoke only a few words of it to me — until his last day in the hospital. He was one of eight patients being discharged back to the detainee tent camp. At that time we did not have culturally appropriate clothing available for the detainees to wear back to the camp. Often, the only clothes they had were the old, dirty garments they were captured in or the paper shorts and tops that the hospital issued. That particular day we had only a few clean cloth hospital jackets to give to the patients who were leaving — not enough for everyone.

Somehow, the young men got the clothing, and the general was going to have to go back to the camp bare chested in paper shorts. Our staff tried to find something for him but came up short. I decided to bend to his age and status.

In spite of how younger people may feel, in Arabic culture the elderly still get respect. I asked a young man who had gotten one of the nicer jackets to give it up for the general. He reluctantly gave it to me, and I handed it to the older man. One of our soldiers gave the young man a clean T-shirt from his own clothes supply.

Just before the eight detainees were removed from the ward, the general looked at me and I went over to him to say good-bye. In flawless English, he said, "Thank you, Madam, for your good care of me. I am grateful to you for that. In another time and another place, you and I could have been friends. I wish you safe travels back to your home."

He touched my hand lightly and slowly walked away with the others, escorted by an MP.

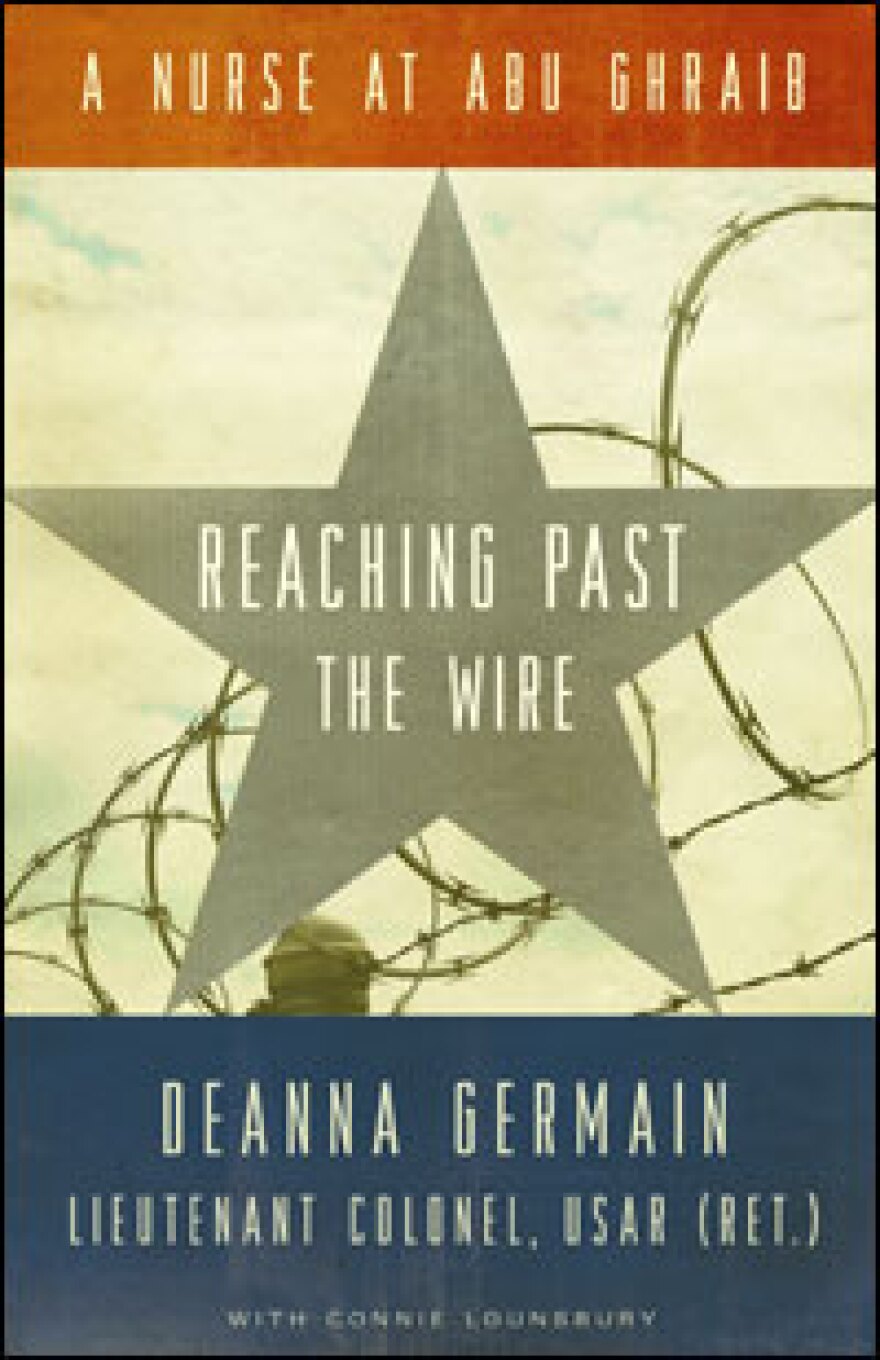

From Reaching Past the Wire: A Nurse at Abu Ghraib, by Lieutenant Colonel Deanna Germain, USAR (Ret.) with Connie Lounsbury. Copyright © 2007 by Deanna Germain and Connie Lounsbury. Published by Borealis Books. All rights reserved.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDM3NjYwMjA5MDE1MjA1MzQ1NDk1N2ZmZQ004))