Introduction

Just this morning, a front-page story told of the enormous demand throughout the United States for courses in English as a Second Language (ESL). Immigrants, regardless of their economic, legal, or employment status, know that speaking English increases their potential at work and play. Learning a language as a youngster is easier than as an adult. At any age it can be grueling, painful, aggravating, fulfilling, amusing, instructive, gratifying, and rewarding—sometimes all of these, sometimes all at once.

When my wife came home from her first day in ESL class, I asked what she had learned. "Oh, really?" Regla replied. "That's interesting." Her first four words in English showed polite curiosity and superficial nicety. In fact, to everything I asked, she responded, "Oh, really? That's interesting." What was the teacher like? "Oh, really? That's interesting." Were there many other students? "Oh, really? That's interesting." Did you break for lunch? "Oh, really? That's interesting." Over the years it's become a running gag.

Regla's first ESL class took place at a neighborhood community center that offered free courses as a public service. Her fellow students were mainly the wives of day laborers and of recently arrived campesinos. She next took a semester at a university ESL center, where her classmates were doctors, physicists, engineers, economists, and chemists—not the image of typical ESL students, but just as anxious to learn a new language. Finally she completed her ESL studies at a community college.

Early on in this country's history, local schools often offered instruction in the language of its main immigrant student population combined, frequently, with English. States passed English instruction laws toward the end of the 19th century, only to repeal them not long after. Some cities, though, did away with bilingual classes altogether and relegated foreign languages to high school instruction only.

When waves of Italian and Eastern European immigrants arrived in the early 1900s, philanthropists underwrote night school English classes, notes James Crawford, an authority on bilingual education, "while indoctrinating immigrants in 'free enterprise' values." Industrialists such as Henry Ford insisted his employees attend loyalty classes, and "an ideological link was forged between language and 'Americanism.'" After the Spanish-American War, an effort to force public schools on the newly acquired island of Puerto Rico to teach only in English was so disastrous that soon the attempt at linguistic colonization was diluted and eventually, after World War II, abandoned.

"We have room for but one language in this country," Theodore Roosevelt wrote ten years after he left the presidency, "and that is the English language, for we intend to see that the crucible turns out people as Americans...and not as dwellers in a polyglot boarding house." Roosevelt pushed for more classes for immigrants to learn English, but also "the deportation of those who failed to do so within five years." This attitude got a boost in Nebraska, where, in 1919, the legislature passed a statute that English "become the mother tongue of all children reared in this state." (The U.S. Supreme Court overturned that law four years later in Meyer v. Nebraska.)

There isn't just one way to learn English, as the contributors to this collection prove. Most of them built their English on a foundation of Spanish (or Portuguese). And most of the immigrants who tackle English today start with this underpinning. Just 75 years ago, though, the source of most immigration was European. In The Education of H*Y*M*A*N K*A*P*L*A*N, a droll 1937 entertainment by Leonard Q. Ross, all the students at New York's American Night Preparatory School for Adults came from Germany or Poland. Ross, the pen name of Polish immigrant Leo Rosten, author of The Joys of Yiddish, wrote of one student whose remarkable contortions of the English language constantly bewildered his exasperated teacher Mr. Parkhill. The beguiling and innocent Mr. Kaplan, who always signed his name with asterisks between capital letters, told the class that the plural of blouse was blice, of sandwich was delicatessen, and that among United States presidents were Judge Vashington, James Medicine, and Abram Lincohen.

Upper-class foreigners, in the days when working-class Hyman Kaplan took courses, were taught through a new approach called English as a Second Language. By the 1950s, ESL had spread to all levels to combat "cultural deprivation" and "language disability," as one account had it.

My own upbringing was entirely in English, surrounded by wall-to-wall books and a surfeit of daily newspapers. When my parents didn't want us to understand them, they spoke household Yiddish. In the late 1960s I moved to the American Southwest, and over the years have often traveled from there into Latin America. In both places, I have met innumerable people for whom English was a second language and have become intrigued with how they acquired this new way of speaking and how it affected their lives. Increasingly my personal and professional friendships developed with those for whom English was not native, as mine was, but another layer. Finally, I married into a Spanish-speaking family and watched in admiration as first my wife, and then my stepsons, learned American English and adapted to its cultural foibles, inexplicable idioms, and linguistic idiosyncrasies.

The contributors to this book are neither culturally deprived nor linguistically disabled. On the contrary, they each have something to contribute to the English-speaking world. Many speak more than two languages. I've always thought that speaking a second language could make you more mentally agile but not necessarily smarter. I've known plenty of people whose lingual was more semi than bi. Yet by the time someone adds a third language to the mix they're either on the ball or on the run.

The killer in English, as in all languages, is the preposition. Nowhere did this strike me more than in Manhattan, where Regla and I once sublet a fifth-floor apartment in a heavily Dominican neighborhood near 145th Street and Broadway. The building super, whose apartment was situated next to the elevator in the lobby, had posted a sign on his front door, with an American flag near the top. Thank you, America, it read, for all that you have done to us. Was ever a preposition so artfully misconstrued?

I rather like the notion of Theodore Roosevelt's polyglot boardinghouse and would be happy to lodge there. I suspect many of this book's contributors would stay there as well. In fact, we may have already done that, dear reader, and what follows just may be a transcript of our multilingual arguments and pontifications going deep into the night. Now that's interesting.

* * *

Learning English by the Sinatra Method

by Congressman José Serrano

People learn second languages in strange ways. My experience has to rank among the strangest. I was born and spent my first seven years in Mayagüez, Puerto Rico, where everyone I knew spoke only Spanish.

My father served with the U.S. military in World War II. When he was discharged, he came home with a stack of Frank Sinatra 78-rpm records. Like many Puerto Ricans, music was a huge part of our lives. I spent hours listening to those records and sometimes singing along.

Little did I know, but those records were teaching me the language of the mainland, where my family would soon move. Listening to Sinatra, I learned to pronounce every word distinctly. He never swallowed a syllable. From him I learned rhythms, inflections, and the sounds of a language that was so different from the one I spoke everyday.

Soon we moved to New York, where my education in English continued. I went to a school where everyone spoke English and began to fill out my vocabulary. From Sinatra records I learned to say "Tewsday," like he did, not "Toosday," like everyone else. But even dearer to my heart and similar to my Sinatra English lessons, I listened to Mel Allen do the play-by-play for the Yankees and a young Vin Scully broadcast the Brooklyn Dodgers. Glued to the radio following the exploits of my heroes, I absorbed the language of excitement and disappointment. I learned storytelling and the art of filling dead time.

As I look back on learning a second language, I always think about the doors it opened for me. I can communicate with people from so many different backgrounds and personal experiences in their native tongues. This skill is invaluable as a leader and a community figure. I must listen and talk to people in language they can understand. The words that I choose have more importance to them than when I talk casually with my family or friends. I am making a connection with them through language—and my special awareness of the power and meaning of words serves me in that endeavor.

I have spent considerable energy in Congress beating back efforts to make English the official language of the United States. I always offer an alternative. I want to recognize English as the primary language in the United States and promote the acquisition of English language abilities by all Americans. But perhaps most importantly, my legislative proposal recognizes that multilingualism ensures a greater understanding among the diverse groups of people that compose the fabric of this nation.

Learning and knowing more than one language is an invaluable skill. I often think what my life would have been like if I had never heard Sinatra as a kid. Without those 78s, there's no way of knowing where I would have gone, or what I would have done, but it is safe to say that my life would have been far different.

Frank Sinatra once said, "I think my greatest ambition in life is to pass on to others what I know." I like to live by those words. One of the things that I know is that language is an invaluable tool. The more tools you have for life, the better equipped you are for whatever life will throw at you.

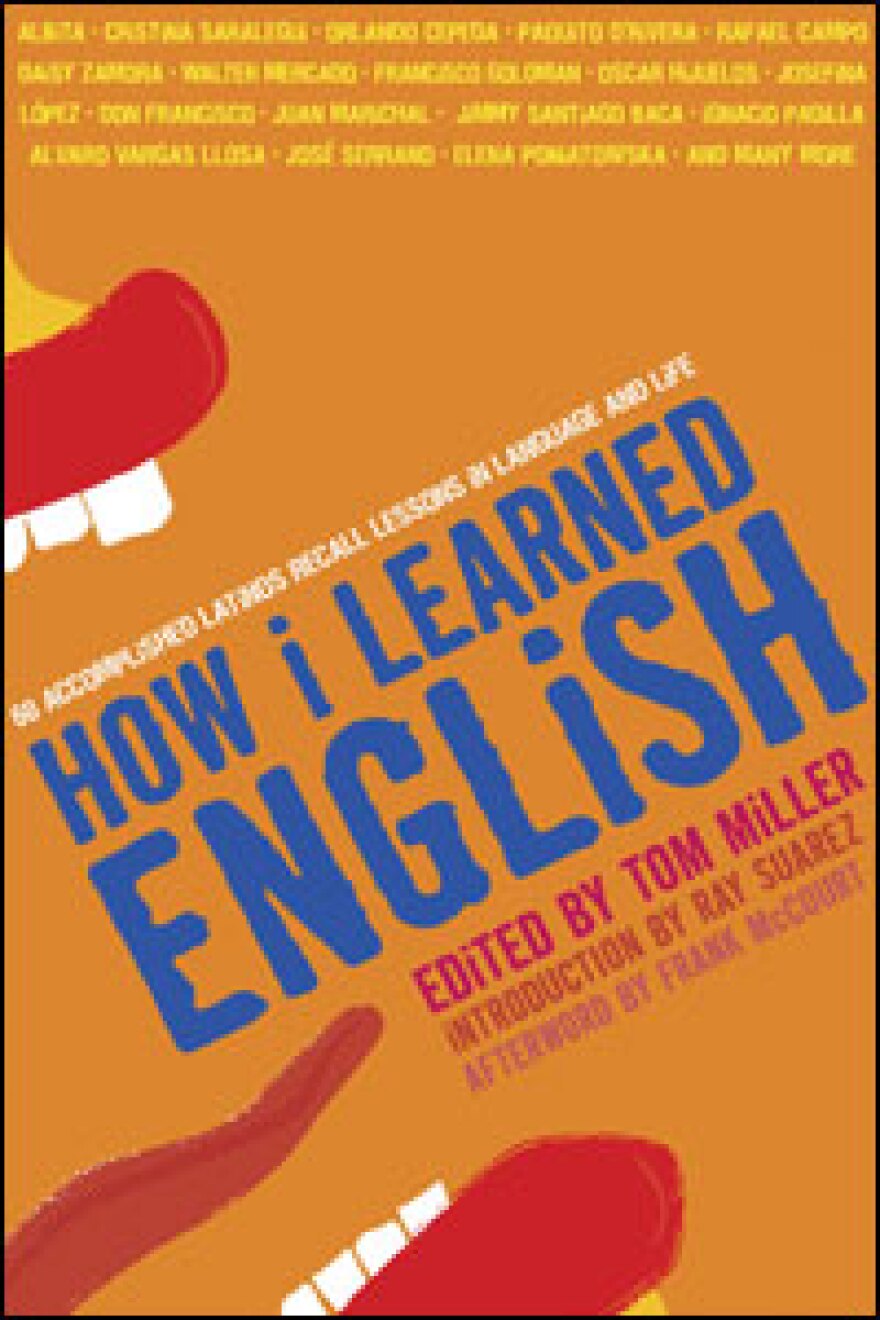

Reprinted with permission of the National Geographic Society from the book How I Learned English edited by Tom Miller. Copyright ©2007 Tom Miller.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDM3NjYwMjA5MDE1MjA1MzQ1NDk1N2ZmZQ004))