Chapter One: Black Forest

In the brisk Indian summer of 1991, Black Forest, Colorado, was a high-end suburban enclave waiting to happen. With its spectacular mountain vistas and free-ranging alpine meadows, the wedge of land between I-25 and Highway 24, just north of the rapidly expanding reach of Colorado Springs, was a prime piece of real estate, a developer's dream. Directly across the interstate from the United States Air Force Academy, Black Forest was poised to become the latest in a long string of upscale bedroom communities encroaching from Greater Denver, two hours to the north.

In the meantime, however, the 200,000 acres of unincorporated El Paso County clung stubbornly to their bucolic charms. Named by an early German immigrant for the similarity of its dark ponderosa pines to the forests of his native Bavaria, the land, teaming with wildlife, was ideal for camping, hiking, and horseback riding. Nearly 8,000 feet at its highest elevations, Black Forest was in fact largely given over to grasslands so spacious that most of the subsequent housing sites would be lopped off in sprawling five-acre parcels.

But there was at the same time something austere and desolate about this all-but-virgin land, especially now, as summer's heat gave way to the first chill of impending autumn sweeping down off the towering reaches of Pike's Peak and the Rampart range. Bisected midway by the crosshair intersection of Black Forest Road and Shoup Road, most of the region ran out along unpaved arteries, dead-ending at the horizon. Its high-end residential future notwithstanding, Black Forest seemed remote from the heartland bustle of nearby Colorado Springs, one of the most prosperous communities on the western edge of Middle America. It's a region that literally embodies the nation's faith and fighting power in a plethora of local military bases and an intense concentration of evangelical outreach organizations.

A pioneering spirit lingered across this windswept expanse of meadow and primeval forest, with homesteaders clearing space for double-wides down dusty roads from which, one day, McMansions and spacious residential streets would spring. Before it became one of Colorado Springs' better suburbs, Black Forest was home to more than a few who cling to the outskirts of society.

Not that the Church family were outsiders. Far from it. Michael and Diane Church may have had few neighbors along their sparsely populated stretch of Eastonville Road, bounding the northern quadrant of Black Forest, but they were still citizens in good standing in the newly minted community. Their thirteen-year-old daughter Heather attended nearby Falcon Middle School, while two of her three younger brothers—Gunner, seven, and Kristoff, ten—were active in the local Boy Scout troop. The whole family regularly attended the area's Mormon church, and they were an integral part of a tight circle of fellow Latter Day Saints and its built-in social and spiritual network. Black Forest was a good place to put down roots, and that's just what the Churches had worked so hard to accomplish.

But the roots had withered. That summer Diane filed for divorce, marking the end of a thirteen-year union that the onetime college sweethearts both acknowledged had long since been over. For a time Diane had attended group counseling sessions for women. Michael, meanwhile, maintained his job as a metrologist at Atmel, a Honeywell offshoot, calibrating tolerances for semiconductors in the region's fledgling high-tech sector. He had moved into town pending the dissolution of their troubled marriage, set to be finalized before the holidays. He left behind a forlorn aura that hung over the Churches' home that September, a lonely, quietly bereft aspect that well suited its remoteness and seclusion. The couple had recently put the property up for sale.

Situated on a 5.8-acre lot a quarter-mile down a badly maintained track from the Eastonville Road and all but hidden from view by wooded bluffs, the Church residence was a small single-family home with four bedrooms, one of which served as a family den. Decked out in a lackluster southwestern motif with a flat roof and tacked-on exterior beams, its windows, trimmed bright blue against the peach-colored stucco walls, overlooked a vista of desiccated grasslands spiderwebbed by narrow roads. A low cinder-block wall sheltered a half-finished patio, and a small garden of mountain flowers was strewn with boulders and a de rigueur rustic wagon wheel. There were other houses scattered across the sward, but the inescapable impression was of a place well off the beaten track, a homestead stubbornly clinging to a bare patch of land and the fading dreams of the family inside.

It was 8:30 PM on the evening of September 17, 1991—the moist air presaging a damp night to come—when Diane Church put in a call to home. A petite, vivacious forty-one-year-old with auburn-tinged hair, Diane still had traces of a southern accent from the Ashland, Kentucky, upbringing she shared with her identical twin sister Denise. She had earlier driven Kris and Gunner to a Scout meeting at their local Mormon church some fifteen miles down the Black Forest Road and had stayed on to attend a women's homemaking class, leaving her daughter Heather to watch over her five-year-old brother Sage, the youngest of the four Church children. Heather had been especially anxious to please her mother, volunteering to babysit and straightening her room without being asked, all because she had been granted permission to attend a school dance scheduled for that Friday.

After an hour of housekeeping dos and don'ts, the class was over. Diane stayed on to talk with friends. She took time out to check on Heather, concerned, she later recalled, because Sage had just gotten his multipurpose DPT vaccination shot earlier that same day, and she wanted her daughter to keep an eye out for any adverse reactions.

At thirteen, Heather Dawn Church still seemed a safe distance from the perilous shoals of adolescence. Measuring only five feet tall and weighing a slight seventy-eight pounds, her sharp oval face was dominated by the oversized front teeth she had yet to grow into and huge pair of brown-framed, thick-lensed glasses, magnifying her hazel eyes even as they seemed to diminish the rest of her already elfin features. She wore her light-brown hair shoulder length in the tight-permed fashion of the day, acknowledging her impending maturity only with the gaudy pairs of plastic earrings she often wore in her triple-pierced lobes. It was the unfinished countenance of a child, still waiting for all the pieces to fit together.

In some way similar, Heather was also assembling the first tentative elements of her own identity. Earnestly studying the violin, she was nonetheless concerned about her participation in a class talent contest and finally decided on handing out caramels to her schoolmates, announcing, "I don't dance. I don't sing. I don't play a musical instrument. I don't do cartwheels. But I sure do love candy." An A and B student who had recently tested for Falcon's eighth-grade gifted program, she had so far evaded drugs and alcohol and the other pressures of her peer group, thanks largely to her parents' decision to avoid suburban snares by locating to this secluded area. It was a measure of the Mormon Church's centrality to the family's life that on a Sunday-school questionnaire asking where she wanted to be in ten years' time, Heather had answered, "I'd like to be on my mission," referring to the mandatory evangelizing work required from every member of the Church of Latter Day Saints. Australia was her choice of mission field, while Brigham Young, her parents' alma mater, was the university she most hoped to attend. Yet even as she held closely to the family's avowed articles of faith, she was also beginning, however hesitantly, to find herself. "Tall, blue-eyed, blond hair," may have been the typical response to the question "What do you want your husband to look like?" but there were imaginative hints of individuality elsewhere in Heather's responses, as when she was asked the name and number of children she would want to have. "One," she replied: a girl, to be named, beguilingly, Persephone.

When Diane called in the mid-evening, Heather and Sage were settled in the family room watching the end of an episode of Home Improvement. It was past the boy's bedtime, but as Heather explained to her mother, she had allowed him to stay up especially to watch the popular sitcom with its idealized family dynamics. Cautioning her daughter to keep an eye out for signs of a fever and reassured of her children's well-being, Diane hung up. "I love you," she would later remember telling Heather, promising to be home by ten.

It was only natural that Diane would have felt an extra measure of concern, especially where it touched Heather. Her oldest child had been born shortly after her marriage to Michael, who, more than a decade later, still had the fit and well-maintained physique that had initially attracted her. Heather had had the longest stretch of all her children to form a strong bond with her father and stood to suffer the most from the disintegrating marriage, since her siblings were still too young to understand fully what was happening to the family. Diane's faith helped sustain her through this difficult transition, but she also suspected that prayer could go only so far in helping her daughter come to terms with the insecurity and guilt that were all too often the outcome of divorce for a sensitive child.

Yet, in the seven months since Diane's husband had moved out, Heather hadn't displayed any outward signs of trauma, thanks in part to the open visitation agreement she had arranged with Michael. To all appearances Heather had taken her parents' separation in stride, and any overt reaction, from inappropriate anger to delinquent behavior, hadn't manifested itself. Against the odds, Heather seemed to be a happy, well-adjusted young girl on the cusp of puberty. If the family crisis had wounded her, she was either hiding the hurt or had yet to face its reality.

Thanks to solicitous friends lending their ears and offering sympathetic advice on her troubles, Diane was fifteen minutes late arriving home that evening, at 10:15. In the back seat of the car, still in their Scout uniforms, Kris and Gunner were already drifting off to sleep as the headlights cut through the thick darkness of the high, empty vista that opened from the Churches' front yard, already partially obscured by a gathering fog. Pulling into the driveway, the first thing she noticed was that most of the house lights were off: Either Heather and Sage were already in bed or, more likely, her daughter was watching television in the dark, as was her inclination. Trailed by the sleepy boys, she crossed the driveway to a pair of sliding glass doors at one side of the home, her house keys at the ready. But she didn't need them: the patio door was unlocked, a fact that momentarily puzzled her, since on leaving at 5:30, she had made sure that all the doors on the property were secured. Still, the family had two cats, and it seemed likely that Heather had let them out for the night and forgot to lock the door behind her.

Inside, the house was in its usual lived-in condition yet still orderly enough for Diane to register that one of the dining-room chairs was tilted against the table. Not the way she'd left things, but kids would certainly be kids.

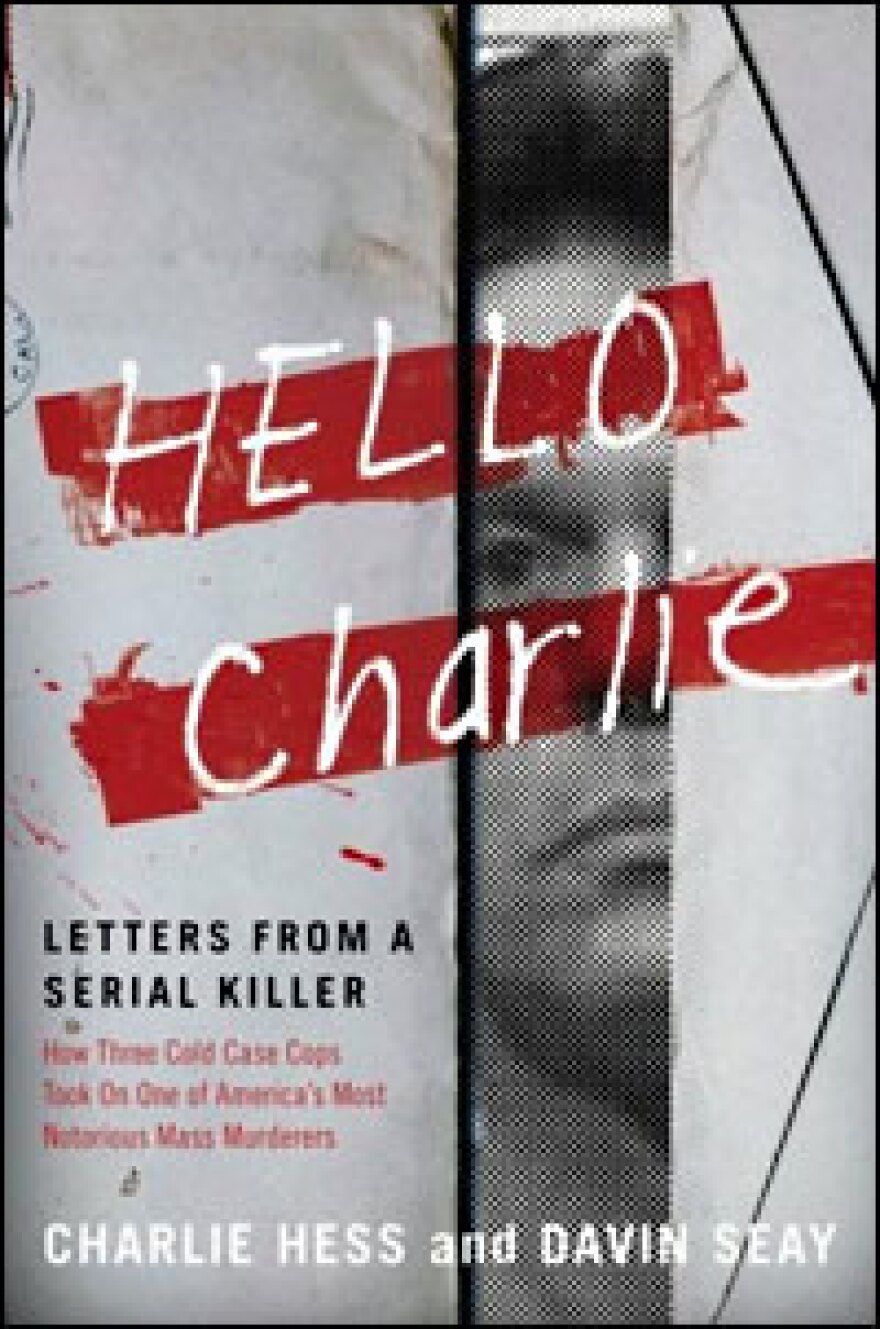

Copyright © 2008 by Charlie Hess and Davin Seay.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDM3NjYwMjA5MDE1MjA1MzQ1NDk1N2ZmZQ004))