When I was asked to contribute to an anthology about the gorgeous minutia of baseball, I didn't have to think for even a second about a topic. I'd wanted to write about my baseball glove for years. Not only is it the single most personal object that I own — the one thing I would be devastated to lose — it is my last, best connection to the baseball that defined my life as a kid. Not just playing the game incessantly, but being a crazy fan of it, too. My glove is a reminder that the innocence and thrill that made baseball so great and so important still exists in this thirty-year-old hunk of leather.

"I'll tell you what. It's sure broken in perfect."

In my forty-three years on Earth, this ranks among the highest compliments I have received. Right up there, definitely top five, maybe No. 1. So tell me more, Bob Clevenhagen, you curmudgeonly craftsman extraordinaire, you seen-it-all, stitched-'em-all Boswell of the baseball glove, you National Archive of five-fingered-leather historical facts and figures, you Ravel of Rawlings Sporting Goods.

"It's broken in as well as any I ever get," Bob says. On the other end of the telephone line, I smile so hard that blood vessels threaten to pop in my cheeks. After all, Bob has been making and repairing gloves for current and future Hall of Famers for three decades. "The target for you is the base of your index finger, not the web. That's the way the pro player would do it. Not the retail market. Not a softball player."

Hell, no! Not the retail market! Not a softball player!

"This looks like a major-league gamer."

I move from happiness to rapture. In fact, I might just cry.

"That's high praise," I manage to say, filling dead air when what I really want to do is drop the phone and dance.

"Yes, it is," Bob replies, curt, gruff, no nonsense, Midwestern. He's just the third person in the one-hundred-nineteen-year history of Rawlings to hold the exalted title of Glove Designer, not a man given to bromides and bon mots, which of course makes his words all the sweeter. "Yours looks like — well, look in the Hall of Fame."

I may spontaneously combust.

"Those gloves probably look just like yours. Same color, same shape, same faded-out look," he says. "It's just a nice-looking glove."

***

My glove isn't just broken in perfect, to quote Bob. I believe it is stunningly perfect, consummately perfect, why-would-anyone-use-anything-else? perfect. To play baseball well, you have to consider your glove an ideal; if not, it will let you down. A glove has to feel like an extension of your hand, something over which you have the motor control of a surgeon repairing a capillary. But my glove is more than just a piece of equipment that works for me. I really think it is empirically flawless.

Let's start with its shape: parabolic from the top of the thumb to the tip of the pinkie. This is the result of years of pushing those two fingers toward the middle; there's a slight break about three inches from the end of each digit. No ball is leaving my glove because it bent back one of the outermost fingers.

When I put the glove on, the first thing I inevitably do is press down the index finger. This transforms the parabola into a circle. Open your palm and spread your fingers wide. Now curl your fingertips forward. That's what my stationary glove looks like.

My glove is soft. It collapses of its own accord when set down. But, thanks to its aforementioned shape, it never falls completely flat, full thumb atop full pinkie. Instead, the tip of the thumb and the tip of the pinkie touch delicately, like God reaching out to Adam on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. I've never understood gloves that open to a V and shut like a book. The idea is to catch a round ball, not a triangular block. Roundness is essential. Softness is, too. The trick is to create a glove pliable enough to respond to your slightest movement. To bend to a player's will, a glove needs to bend. Mine does.

The index finger of my left hand — I throw right-handed — lies on the exterior of the glove's back, the only digit not tucked inside. This technique provides bonus protection when catching hard-hit or fast-thrown balls. I believe it also helps me better control the glove's behavior. And it looks cool.

Each finger curves gently, like a suburban cul-de-sac. The adjustable loops surrounding the pinkie and thumb aren't tied too tightly, but their existence is palpable. The web isn't soft and deep, so that a ball might get lost, but rather follows the natural curvature from the top of the index finger to the top of the thumb. The heel of my glove aligns with the heel of my palm. The shearling beneath the wrist strap is matted but still recognizable. There are no garish personal adornments, just my first initial and last name written meticulously in black ink letters three-eighths of an inch tall just above the seam along the thumb. It looks as if I used a ruler to line the letters up.

Then there's the smell: leather, dirt, grass, saliva, sun, spring, childhood, summer, hope, skill, anticipation, achievement, fulfillment, memory, love, joy.

***

I bought my glove in the spring of 1977. I was about to turn fourteen, out of Little League and over my head in the ninety-feet-to-first-base Senior League in the inner suburb of Pelham, New York. A wall of leather graced the sporting goods store in a nearby town, soft porn in my baseball-centric world. I had to have a Rawlings — it would be my third or fourth Rawlings, one of them royal blue — because that's what major leaguers wore. And it had to be a good one because, while every other kid pined for his turn at bat, I happily chased grounders until dark. Five feet tall and under a hundred pounds, I was a typical prepubescent second baseman: all field, no hit. An adult-sized glove would make me feel bigger, and play bigger.

My choice, the XPG6, was expensive. I remember the price as $90, though old Rawlings catalogues tell me it was probably $70 (or we were ripped off). I didn't know it then, but it was fourth-priciest glove in the Rawlings line. Thanks, Mom, for not blinking.

Not insignificantly, the XPG6 reminded me of the glove my eight-years-older brother wore when he was in high school. Virtually all of my decisions at that age were influenced by my brother, who had taught me how to calculate my batting average when I was in the second grade. (At age nine, clearly my athletic prime, I hit .750, aided, no doubt, by some generous scoring.) He played shortstop and, like me, was a competent but unexceptional player. But his glove was just right: round and bendable. I didn't want his, just one like it.

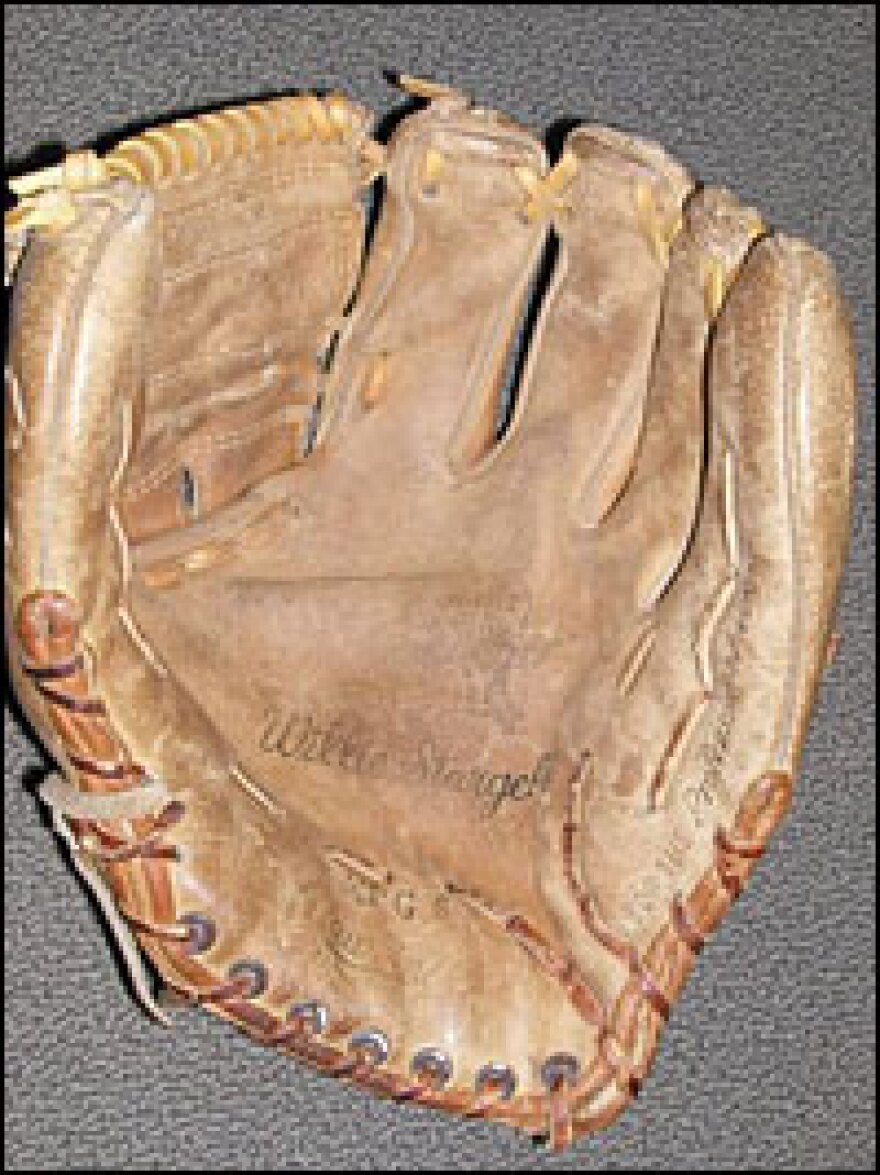

So the XPG6 it was. It bore Rawlings's famous trademarks: HEART OF THE HIDE written inside a snorting steer stamped in the "DEEP WELL" POCKET. The TRIPLE ACTION web with a Spiral Top (in grade-school cursive). Along the thumb, Rawlings's familiar bright-red Circle R. Next to it, another classic, the EDGE-U-CATED HEEL. Below that, the patent number, 2,995,757. (And below that, my first initial and last name. And a single, mysterious, black dot.) Along the glove's heel, XPG6 stamped just above the handsome Rawlings script, with a long, swooping tail on the R, itself resting atop the letters U.S.A. Only the U and the top of the S are discernible today.

Two other marks cemented my love. Explanation is unnecessary as to why, arcing along the pinkie, FOR THE Professional PLAYER was so seductive. The signature's allure was less obvious. My glove was endorsed by Willie Stargell, who (a) threw left-handed and (b) played one hundred eleven games at first base in 1976. Why his autograph — which looked fake, with penmanship-class loops and flourishes — was on what I assumed was a middle infielder's glove was incomprehensible, but I loved its cocktail-conversation quality. When you're fourteen, weird sometimes is good.

It's not a stretch to say that I've had a longer (and closer) relationship with my baseball glove than anyone or anything, apart, maybe, from my immediate family and a couple of childhood pals. I broke it in in the manner of the times: a couple of baseballs, string, the underside of my mattress, ceaseless play. It carried me through my last two years of organized ball, on a team sponsored by the local American Legion post.

A black-and-white team photo hangs framed on my office wall now. It's from the end of the 1977 season, and of the eighth grade. I sit smiling in the front row of wooden bleachers along the first-base line at Glover Field with my friends Peter Derby (shortstop), John McNamara (left field), and Chuck Heaphy (right field, coach's son), and a younger kid whose name I can't remember. My wavy hair wings out from under the two-tone cap with the too-high crown. Black block felt letters spell LEGION across the chests of our double-knit uniforms. We wear what are essentially Detroit Tigers period road grays: black, orange, and white piping along the neck and sleeves of the buttonless jerseys, black stirrups with orange and white stripes stretched as high as possible to reveal as much of our white sanitary socks as possible. The '70s rocked.

The XPG6 rests on my left knee. My index finger pokes out, pointing directly at the camera lens. The leather is dark and rich. I am young and small. The twelve-inch XPG6 is new and large — much too large for me, a glove worn, I have since learned, by big-league outfielders and third basemen. Joe Morgan used a ten-inch glove at second base at the time. But what did I know? (More relevant: what did the salesman know?) All that matters is that, in that photograph, the XPG6 and I look like we're starting life, which, of course, we are.

How did it do for me? Records of my glove's rookie year are lost to history. But my 1978 Legion season is preserved on a single piece of lined white loose-leaf paper, folded inside a schedule, stored with other keepsakes in the basement. It reveals that I played in thirteen games — with nine appearances at second base, four at shortstop, and a few innings at third base and in right field — and committed five errors, two of them in our 9-4 championship-game loss to Cornell Carpet. (The stat sheet also shows that I totaled just four hits in twenty-three at-bats, an average of, ouch, .175. But that I walked sixteen times and had a robust on-base percentage of .404. Billy Beane would have given me a chance.)

I can still see and feel the ball rolling under the XPG6, and through my legs, during tryouts for the junior varsity the next spring, ending my competitive hardball career. But my glove's best years were yet to come. In college, on fast but honest artificial turf at the University of Pennsylvania's historic Franklin Field, my glove snared line drives, grabbed one-hoppers to the shortstop side, shielded me from screaming bullets, and started more 1-6-3 double plays than you'd expect. My team won back-to-back intramural softball championships, and my glove was one of the stars. Later, it performed well on the pitcher's mound again in New York City softball leagues. It shagged hundreds of baseball fungoes lofted heavenward on lazy afternoons by my best friend Jon.

As I aged — knee surgeries, work, a wife and daughter — my glove lay dormant most springs and summers, its color fading and leather peeling: wan, weathered, cracked. But it's always remained in sight, not stashed in a closet or buried in a box of mouldering sports equipment. Single, on a couch, in Brooklyn, the Yankees on TV — married, in Washington, in the attic, at a desk — I put on the XPG6 and whip a ball into its still-perfect pocket. My glove is a comfort.

Excerpted from Anatomy of Baseball (Southern Methodist University Press), edited by Lee Gutkind and Andrew Blauner and reprinted with the permission of the Creative Nonfiction Foundation. Essay copyright 2008 by Stefan Fatsis.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDM3NjYwMjA5MDE1MjA1MzQ1NDk1N2ZmZQ004))