When Glen Carroll travels for work, he takes a pair of black stage pants, a studded belt, and a few shirts, usually in splashy colors like bright red or banana yellow. If he wants to make a more noticeable impression, he might take something flashier, like a cape fashioned from an American flag and a British flag tied together, or a T-shirt imprinted with the Greek omega symbol and paired with a silk scarf, or white football pants with blue knee pads and Capezio dance shoes — an outfit very similar, as it happens, to the one Mick Jagger wore on the Rolling Stones' 1981 tour. For Glen, verisimilitude in dress is part of the job. As the singer of Sticky Fingers, which bills itself as "the leading international Rolling Stones tribute show," he is a kind of rock star proxy, a substitute Mick. And considering that the Rolling Stones tour only once every few years, and that Sticky Fingers has toured every year for the past eighteen years, it's likely that he has sung "Start Me Up," and "Brown Sugar," and "(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction" more times than Mick Jagger himself.

Glen is slim and snake-hipped, with heavy-lidded eyes and a prominent, almost coltish mouth. At forty-seven, he resembles a slightly younger Mick Jagger — the Jagger of, say, Steel Wheels — and wears his brown hair in the same style: short in front, longer and feathery on the sides. Offstage, he favors blue jeans, a blazer, and scuffed loafers, or a T-shirt and motorcycle boots. At all times, he wears a gold Rolex "President" watch. In person, he has a sociable nature and a roguish charm and comes across like the kind of guy you might encounter late at night in a barroom, jive-talking one of the waitresses. As a bandleader, however, he is mercurial and governs by mood. He once threatened to fire the rhythm guitarist because his hair had grown beyond appropriate Ron Wood length. On the other hand, when he's having a good time, and particularly when he's been drinking, he will climb behind the drum kit, to the frustration of more authentic-minded band members. "Who ever heard of Mick Jagger playing the drums?" the drummer once remarked, exasperated. Glen is equally contradictory in appraising his own talents, swinging between modesty and extreme boastfulness. "I know what it's like to walk in Mick's shoes — with lift supports, mind you," he once told me. He has also told me, "If you want me to go out and front a band, I'll do it as good as maybe ten other guys in the world can do it."

In fact, Sticky Fingers has had considerable success. The band, which is based in the New York — New Jersey area, travels all over the country, performing at rock clubs, bars, biker rallies, birthdays and weddings, casinos, corporate events, and colleges, being especially popular at fraternity houses in the South, where Sticky Fingers has become a fixture of Greek life, as indelible as keg stands and hazing. A few years ago, Sticky Fingers flew to Rotterdam, Netherlands, to appear at a "tribute fest" in the Ahoy arena and performed along with other tribute bands in front of eleven thousand people. Bruce Springsteen played the same venue the following night. Most engagements, however, are less glamorous. Tribute bands occupy the lower rungs of the show-business ladder, somewhere between lounge bands and wedding singers, and even a successful act like Sticky Fingers leads a schizophrenic existence. I spent a year hanging out with the band members, and for every Ahoy arena, there were a dozen times when they drove hundreds of miles to play at a tiny bar or frat house, spent the night in a cheap motel or none at all, and returned home with neither wealth nor glory. Such experiences never dampened their enthusiasm to go back out and play again.

For most people, tribute bands are a hobby, a chance to assume the role of the musical heroes of their youth. But Glen is the rare tribute performer who has turned being someone else into a full-time endeavor, and in conversation he gives the impression he's spent the past decade sharing a tour bus with the Marshall Tucker Band. He speaks in the animated, slangy palaver of an FM disc jockey and uses words like gig and backline. Describing a former drummer, he says, "Tightest pocket I've ever heard — cat could play reggae like only the natives can." He carries himself like an old-hand rock star, too; when I visited him at home, he drove me around in a Mercedes convertible while drinking a vodka-cranberry from a rocks glass. From habit, he occasionally slipped into a British accent. It's difficult not to experience confusion between his dual lives: in his role as Mick Jagger, he has signed autographs, posed for pictures, been flown around the world, attracted beautiful women, appeared in magazines and on television. Returning home he is met with obscurity. As he likes to say, "Here's this average guy who pays his cable bill and takes out the trash like everyone else, but he gets to experience some of what it's like to be a rock star." When he says this, I often smile to myself; average guy does not come to mind when I think of Glen.

I first met Glen Carroll a few years ago, when a magazine I was working for at the time was planning a music issue and I suggested an article about tribute bands. Tribute bands might seem a lightweight subject, but on closer examination they reveal semi-serious things about our culture: our celebrity worship, the baby boomer nostalgia that pervades modern entertainment, the seeming exhaustion of new ideas in art, film, fashion, music. In fact, the essential notion of a tribute band — that is, something directly inspired by what has gone before—extends beyond music to the entire culture. Stephen Colbert is, in a way, a tribute band to Bill O'Reilly. Quentin Tarantino is a tribute band to 1970s blaxploitation and B movies. You could think of Dita Von Teese as a tribute band to the fifties sex symbol Bettie Page. Gus Van Sant's shot-for-shot remake of Psycho is unquestionably a tribute band to the Alfred Hitchcock original. Karaoke is based on the same premise as a tribute band, as is the popular video game Guitar Hero, in which players replicate, note for note, famous guitar solos.

Tribute bands are indicative of the desire for easy fame without accomplishment because their lure is this: by putting on a black wig and a top hat, you can become Slash from Guns N' Roses, a guitar god. Most tribute performers either dreamed of being rock stars but ended up working more mundane jobs instead or they actually pursued a career in music that didn't work out. Maybe they were talented, but not talented enough. Or maybe they formed a roots-rock band and wrote earnest songs about the heartland and, in search of a record deal, moved to Hollywood in 1985, right around the time the record companies were signing the flashy hair-metal bands. Playing in a tribute band offers a second chance to experience stardom, however refracted. It is basically wish fulfillment — the rock and roll equivalent of those fantasy baseball camps where grown men suit up and take the field and bat balls around, something I've always found a little melancholy, but sort of endearing, too. Something else I find appealing about tribute bands is that they are unabashed believers in rock and roll, at a time when the form appears to have hit a dry spell. Record sales have declined for the past decade. Legendary rock clubs like CBGB have closed. Video games, the Internet, and cable TV all compete with music for primacy in the teenage head. And technology and changing times are eliminating many of the tribal rites surrounding rock and roll. I once listened to a fairly famous drummer who had grown up on Long Island in the seventies talk fondly of camping on line to buy concert tickets to see The Who. Halfway through the conversation, I realized Ticketmaster.com had made that custom completely irrelevant. In the same way, the iPod is making irrelevant the full-length album, the album cover, the ritual of studying liner notes, the midnight record store sale, and, eventually, the record store itself. New rituals will develop, of course. But at a tribute show, classic rock culture reigns in all its high-decibel glory. I think of tribute bands as being like those historical reenactors, dressing up and reliving a golden age of rock and roll — a time before the commercial dominance of pop and hip-hop, before DJs replaced live bands, before radio and record company conglomeration, before things like guitar solos and groupies and rock operas became ironic. A great number of tribute musicians belong to this time; they grew up in the seventies and eighties reading Circus and Creem and hanging posters of Jimmy Page and Randy Rhoads on their bedroom wall, and they saw bands like KISS and Black Sabbath in concert long before the reunion tours. Although I am a decade younger, I feel I belong to this time, too. I mostly listen to seventies rock bands like Mott the Hoople and Thin Lizzy and the Faces. I watch a lot of VH1 Classic. I've had long and involved conversations about the guitar tones on Robin Trower's Bridge of Sighs album. Also, I don't own an iPod, or a CD player, or a tape deck, but listen instead to LPs, which puts me four technologies behind the times. Basically, I'm an analog kind of guy. In this way, I share with tribute musicians a longing for the rock music of an earlier time and a sense of displacement in the modern music scene.

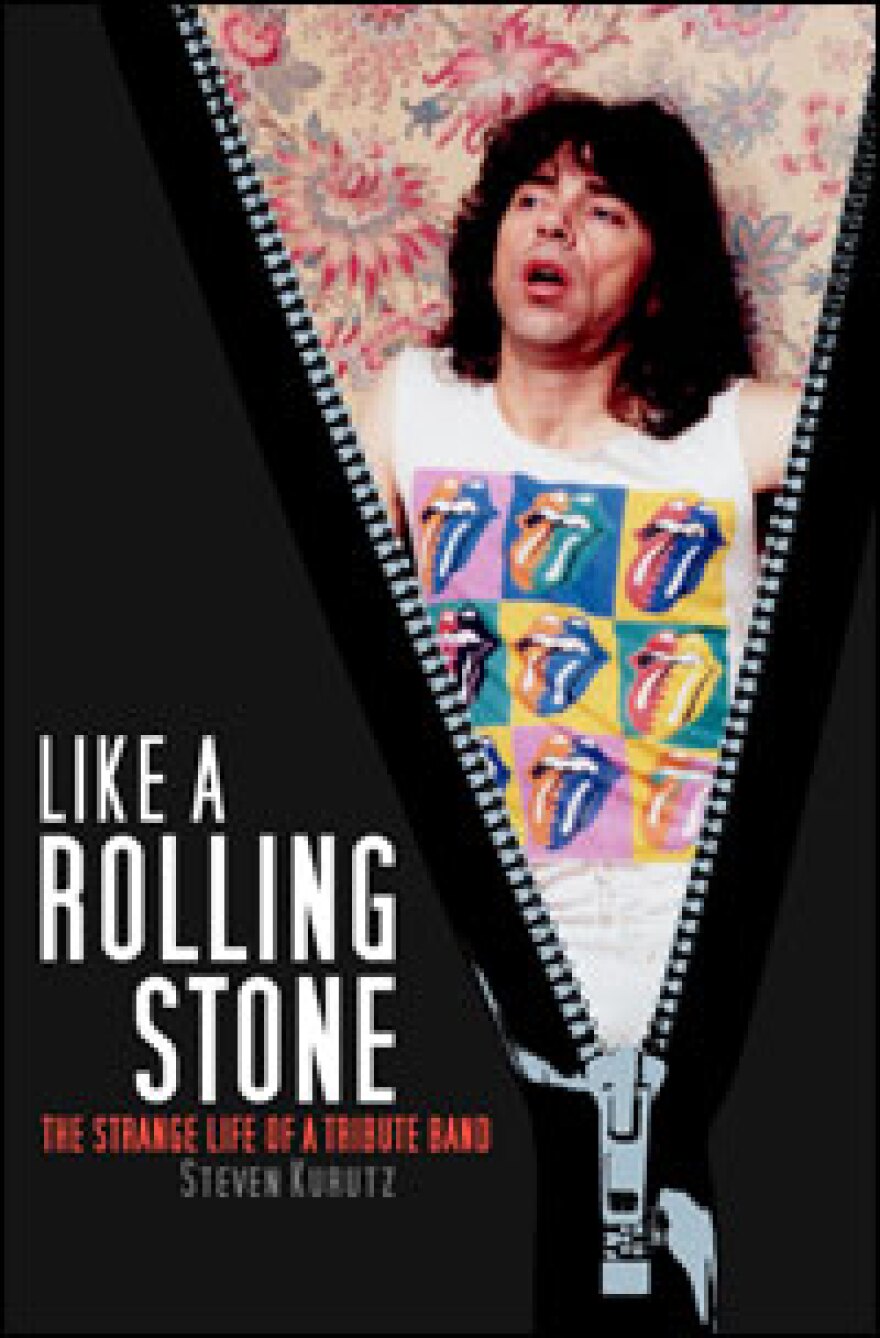

Excerpted from Like a Rolling Stone: The Strange Life of A Tribute Band by Steven Kurutz, by permission of Broadway Books.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDM3NjYwMjA5MDE1MjA1MzQ1NDk1N2ZmZQ004))