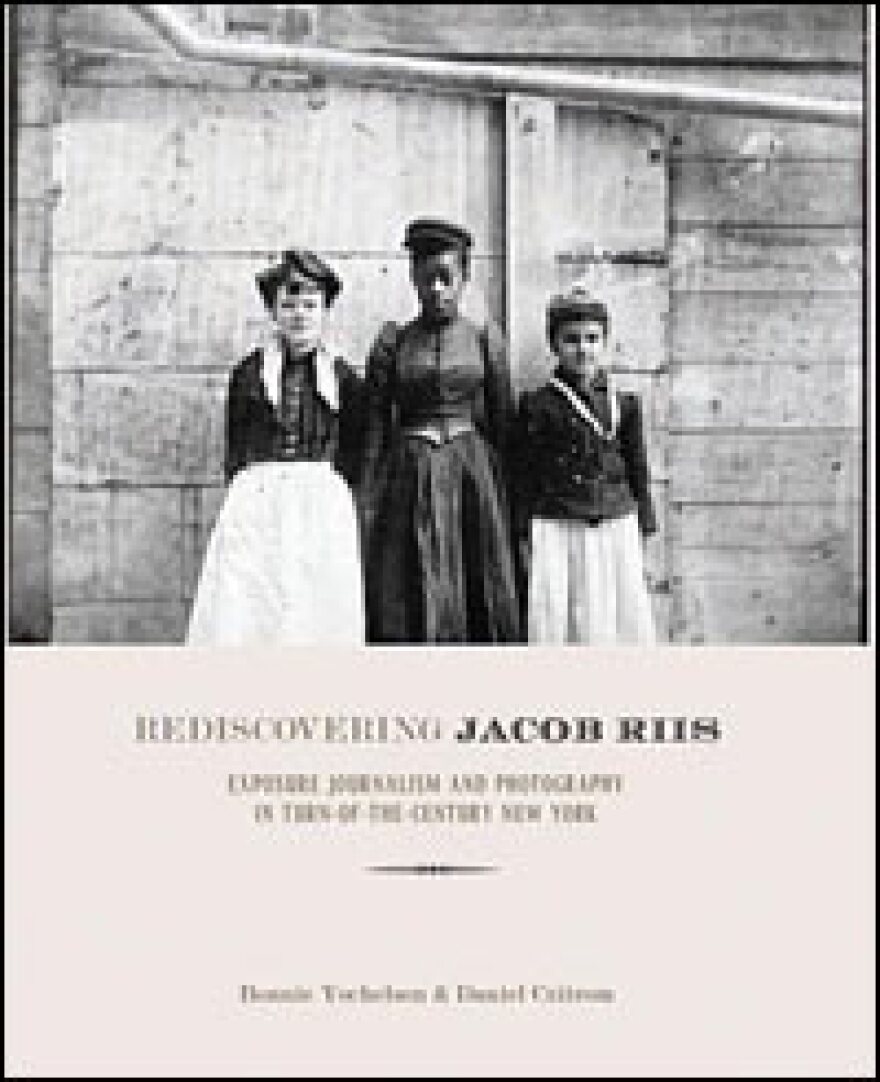

The following excerpt is adapted from the introduction to Rediscovering Jacob Riis.

When Jacob Augustus Riis died on May 25, 1914, at the age of sixty-five, he was a beloved public figure. How the Other Half Lives, his 1890 call-to-conscience for housing reform, had been a bestseller and was still in print. The Making of an American, his popular 1901 autobiography, which told the heartwarming story of his rise from penniless immigrant to confidant of President Theodore Roosevelt, had made him a celebrity. His nationwide lecture tours and steady stream of magazine stories had kept his message in public view. Nearly a century later, Riis maintains a stubbornly persistent hold on the American imagination. The twin themes of his writing—urban poverty and the Americanization of the immigrant—are as relevant today as in his time. The recovery in the 1940s of Riis's original photographs—images of decrepit rear tenements, "black-and-tan dives," newsboys, and "little mothers," which constitute a unique pictorial record of New York's late-nineteenth-century slums—added another dimension to his fame. Indeed, images such as "Bandit's Roost," which was reenacted in the 2002 Hollywood film Gangs of New York, have become emblems of urban poverty.

His most enduring legacy remains the written descriptions, photographs, and analysis of the conditions in which the majority of New Yorkers lived in the late nineteenth century. The new immigrants of the tenements—Italians, Jews, Bohemians, Chinese, Slavs, and "low Irish"—threatened the political stability of the city and the nation. The explosive mixture of grinding poverty, sweatshops, and mass immigration, the growing power of urban Democratic political machines, the declining influence of Protestant evangelical churches, the persistence of life-threatening public health conditions, the increase in child labor and juvenile crime, the "murder of the home"—all these were passionately portrayed in his "Studies Among the Tenements of New York," the subtitle of How the Other Half Lives.

In that first book, Riis employed every means he could muster to arouse his readers: curiosity, humor, shock, fear, guilt, and faith. His passion ignited his audience, but his message was not truly incendiary. A deeply contradictory figure, Riis was a conservative activist and a skillful entertainer who presented controversial ideas in a compelling but ultimately comforting manner. His social scientific method of careful observation and deployment of statistics and photographs would become hallmarks of the Progressive movement, yet his writings hark back to several nineteenth-century literary traditions, including police journalism, Protestant charity writing, the "sunshine and shadow" guidebooks to "the secrets of the great city," and the tales of Horatio Alger. His disturbing photographs were safely embedded in Christian sermons. It was precisely Riis's ability to straddle the old and the new that won the confidence of his audiences and secured his success.

In the writings and lectures that followed How the Other Half Lives Riis stayed on message. But the racial stereotypes faded in favor of anecdotes about individuals, and his photographs also became more personal, with "flashlight" exposures giving way to portraits that evolved naturally out of interviews. Otherwise, the later books and articles are numbingly repetitive. Indeed, by the late 1890s, many of Riis's innovations, such as tenement-life storytelling and photographic illustration, became commonplace, and a change in sensibility occurred that left Riis behind. The shift can be seen, for example, in Stephen Crane's Maggie, A Girl of the Streets (1893), which scandalized the public not because of its subject matter but for its utter lack of moral uplift; or in Lincoln Steffens's The Shame of the Cities (1904), which employed a streetwise, cynical tone to expose government corruption. Steffens, who warmly regarded "Jake" Riis as a mentor, wrote about politics and crime with a clinical detachment that was entirely foreign to Riis.

Although his innovations quickly became commonplace, Riis posed a series of urgent, often implicit, questions to himself and his readers, which remain surprisingly apt today: What is the structural relationship between persistent poverty and new immigrants? If different "races" and nationalities possess inherent moral and cultural characteristics, how can that be reconciled with the American creed of individualism? How does environment shape "character"? What are the proper roles of government, private philanthropy, and religion in reform efforts? How important is spectacle and entertainment in rousing the public conscience?

While the Manhattan slum neighborhoods that Riis documented have been transformed into fabulously lucrative real estate, his work still resonates on a global level. The 2003 United Nations report on The Challenge of Slums presents a grim picture of a planet where more than 900 million people, nearly a third of the world's urban population, live in slums. That figure may reach a staggering 2 billion by 2030. The report summarizes the situation in twenty-nine city case studies with an urgency that echoes Riis: "Slums are distinguished by the poor quality of housing, the poverty of the inhabitants, the lack of public and private services and the poor integration of the inhabitants into the broader community and its opportunities . . . . Slum dwellers have more health problems, less access to education, social services and employment, and most have very low incomes." In Rediscovering Jacob Riis we offer a fresh look at a journalist, reformer, and photographer whose world is long gone, but whose probing imagination, moral passion, and intellectual contradictions are as imperative as ever.

Excerpted from Rediscovering Jacob Riis: Exposure Journalism and Photography In Turn-of-the-Century New York, copyright 2007 by Bonnie Yochelson and Daniel Czitrom

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDM3NjYwMjA5MDE1MjA1MzQ1NDk1N2ZmZQ004))