This first part, I have to warn you, is ugly, and for too long now I've been carrying it alone, going to sleep on it at night and then waking in the dark, my T-shirt soaked through, the images and sounds playing out in my head, even as I tell myself it's just a dream, there's nothing I can do, it's over and done.

Imagine it with me:

Gray dusk, mid-November, the north woods of Minnesota. You're up in a tree, a red maple whose leaves have all dropped, and all around you the late-autumn woods are stirring in preparation for sleep — squirrels barking in descant, a pair of ground sparrows wrestling in the moist, dead leaves, an owl sliding past and fastening itself to the upper branch of a dead spruce thirty feet away. There's still a chance the deer you've been waiting for will show itself, but that's unlikely now and it doesn't matter, because in the silence you've discovered your eyes and your ears and, best of all, your own company, on which someday you'll have to rely.

In other words, you're learning to trust yourself.

I was perched that day cross-legged on a small wooden platform eight or so feet off the ground, my lever-action .30-30 resting in my lap. My hands were so cold and numb that I couldn't persuade them to pluck my watch from the bottom of my ammo pocket where it lay among a dozen unspent brass cartridges. With effort I maneuvered my fingers through zippers and wool and wedged them into my armpits to thaw. They felt like little frozen breakfast sausages, like nothing that belonged to me. When I could move them again, I fished out my watch by its broken band. Five twenty-two, it said. Just a few minutes more of legal shooting time, and then I'd be climbing down from my perch and making my way across the quarter-mile ridge to the old hairy white pine where my dad was sitting, and together the two of us would hike to the car, parked out of sight in the high brown ditchgrass.

For as long as I could remember I had been Dad's pal, his shadow, his right-hand man. I fished and hunted with him. I worked alongside him on his fix-up projects — installing wooden booths in his supper club, the Valhalla, sanding the floors of the ex-governor's old lake-home the year we bought it and moved in there, constructing a sauna in its attic. I hammered, painted, measured, pried and stapled. I tore things down and built them up. There was never a time when I was embarrassed to be seen with my dad, never any real awkwardness between us — though if there had been, I guess it wouldn't matter now. If only I could just close my eyes and will myself back to that day, climb into that tree, grab hold of my collar and yank myself to my feet, say, Go, man, go now — hurry, and then watch that skinny young kid that was me vault out of his deer stand and race through the woods to save his dad, whom he loved. Whom I loved. The problem is, I didn't know he needed saving. And anyway, I'm stuck with how it actually happened, the breeze stiffening out of the northeast, chilling my back and carrying with it the smell of winter coming.

As I watched the sun's pink top falling beneath the treeline, I imagined how good it was going to feel getting thawed out. I imagined Dad and myself in the old hunting car, a giant twenty-year-old Mercury, saw him listen, pleased, to the little revs he produced with his foot, saw him reach into his pocket and throw me a candy bar before spreading his fat grizzly-bear hand in front of the vent to check for heat.

At five thirty I dropped my watch back into my ammo pocket. Then, with my thumb poised to eject the cartridges from my rifle, I heard the single report. Even considering the heavy growth of trees between us, it should have been louder, but that doesn't explain the immediate feeling I had that something was wrong. I thought of Mom at home with Magnus, pictured her at the kitchen window, lovely but taut-faced, the last of the sun chroming her platinum hair.

Guns, she'd always say during hunting season, shaking her head. Years ago she had allowed Dad to teach her how to use his rifle — she'd even gone out into the woods with him a few times. But apparently that was an indulgence from early in the marriage.

I slid to the edge of my flat wooden perch, flipped over on my belly and scrambled down the crude ladder of boards we'd nailed to the maple's trunk. From four or five feet up I jumped, and my knees jammed my chest on impact. I ran. Against all training and good sense, I ran with a loaded rifle through the woods, knowing I should wait for the second shot, the kill shot, before moving, knowing I should stop and unload. I sprinted along the top of the ridge, ducking the shaggy branches of the white pines, stumbling through clumps of red willow and then down the steep slope into the marsh where I crashed through cattails and high-stepped the ice-crusted muck. At the other side, on the edge of a five-acre cluster of white pine and birch, I paused. My heart was going hard, pushing blood out to my fingertips, which tingled, warm. Dad's stand was only forty yards ahead, nailed seven feet up in a dying white pine, but I couldn't see it or him. The sun had gone under by now, and a dirty blue darkness was rising from the forest floor.

Dad! I called, and then moved forward again. I felt my heart beating in my neck and tried to quicken my pace, but then I tripped on a tree root, a long naked thing my eyes picked up only as it hooked my booted toe.

Okay, I said out loud. I got back on my feet, relieved my gun hadn't discharged, and tried to calm myself, slow my breathing. And it was then, just after I'd unloaded my rifle, that I saw him. For a moment I thought he was hiding from me back there behind the rotting trunk of the tipped-over birch tree, waiting to leap up and scare me. But next I saw his orange hunting cap ten feet away, hooked on the branch of a wild caragana, and then I saw his right eye staring past me into the woods — and then I saw where the top of his head should have been.

From the eyebrows up, he was simply gone, poof, blown away. Yet in spite of his ruined head, in spite of the way his right leg was tucked back under him at an angle he never could have managed, I felt certain that he was going to sit up and laugh, reassure me, It's all right, Jesse, everything's okay, because according to him everything always was.

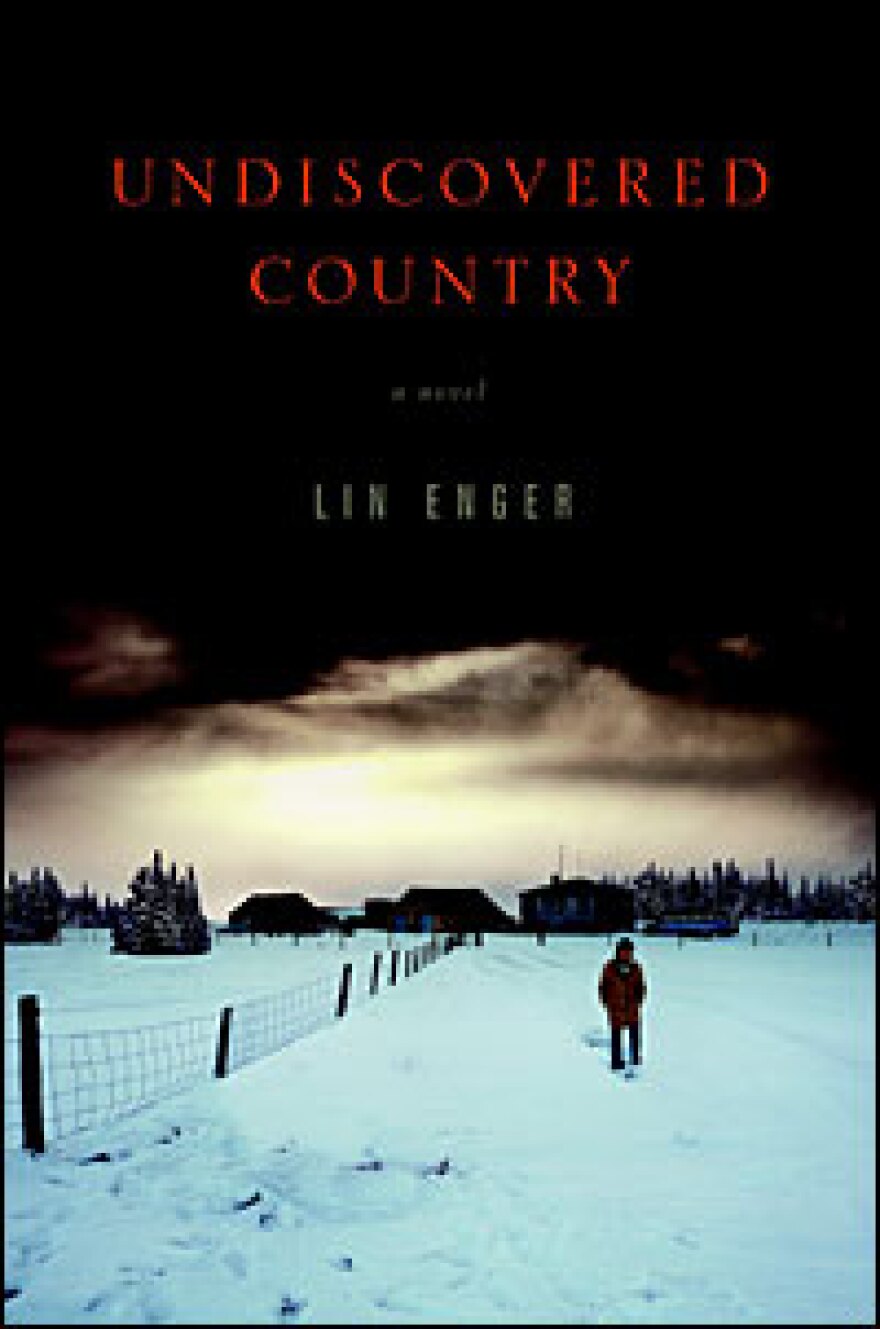

Copyright © 2008 by Lin Enger

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDM3NjYwMjA5MDE1MjA1MzQ1NDk1N2ZmZQ004))