From the short story, 'Loot'

Mathilde's in North Carolina with her husband when she hears about the hurricane—the one that's finally going to fulfill the prophecy about filling the bowl New Orleans is built in. Uh-huh, sure. She's been there a thousand times. She all but yawns.

Aren't they all? goes through her mind.

"A storm like no one's ever seen," the weather guy says, "a storm that will leave the city devastated . . . a storm that . . ."

Blah blah and blah.

But finally, after ten more minutes of media hysteria, she catches on that this time it might be for real. Her first thought is for her home in the Garden District, the one that's been in Tony's family for three generations. Yet she knows there's nothing she can do about that—if the storm takes it, so be it.

Her second thought is for her maid, Cherice Wardell, and Cherice's husband, Charles.

Mathilde and Cherice have been together for twenty-two years. They're like an old married couple. They've spent more time with each other than they have with their husbands. They've taken care of each other when one of them was ill. They've cooked for each other (though Cherice has cooked a good deal more for Mathilde). They"ve shopped together, they've argued, they've shared more secrets than either of them would be comfortable with if they thought about it. They simply chat, the way women do, and things come out, some things that probably shouldn't. Cherice knows intimate facts about Mathilde's sex life, for instance, things she likes to do with Tony, that Mathilde would never tell her white friends.

So Mathilde knows the Wardells plenty well enough to know they aren't about to obey the evacuation order. They never leave when a storm's on the way. They have two big dogs and nowhere to take them. Except for their two children, one of whom is in school in Alabama, and the other in California, the rest of their family lives in New Orleans. So there are no nearby relatives to shelter them. They either can't afford hotels or think they can't (though twice in the past Mathilde has offered to pay for their lodging if they'd only go). Only twice because only twice have Mathilde and Tony heeded the warnings themselves. In past years, before everyone worried so much about the disappearing wetlands and the weakened infrastructure, it was a point of honor for people in New Orleans to ride out hurricanes.

But Mathilde is well aware that this is not the case with the Wardells. This is no challenge to them. They simply don't see the point of leaving. They prefer to play what Mathilde thinks of as Louisiana roulette. Having played it a few times herself, she knows all about it. The Wardells think the traffic will be terrible, that they'll be in the car for seventeen, eighteen hours and still not find a hotel because everything from here to kingdom come's going to be taken even if they could afford it.

"That storm's not gon' come," Cherice always says. "You know it never does. Why I'm gon' pack up these dogs and Charles and go God knows where? You know Mississippi gives me a headache. And I ain't even gon' mention Texas."

To which Mathilde replied gravely one time, "This is your life you're gambling with, Cherice."

And Cherice said, "I think I'm just gon' pray."

But Mathilde will have to try harder this time, especially since she's not there.

Cherice is not surprised to see Mathilde's North Carolina number on her caller ID. "Hey, Mathilde," she says. "How's the weather in Highlands?"

"Cherice, listen. This is the Big One. This time, I mean it, I swear to God, you could be—"

"Uh-huh. Gamblin' with my life and Charles's. Listen, if it's the Big One, I want to be here to see it. I wouldn't miss it for the world."

"Cherice, listen to me. I know I'm not going to convince you—you're the pig-headedest woman I've ever seen. Just promise me something. Go to my house. Take the dogs. Ride it out at my house."

"Take the dogs?" Cherice can't believe what she's hearing. Mathilde never lets her bring the dogs over, won't let them inside her house. Hates dogs, has allergies, thinks they'll pee on her furniture. She loves Mathilde, but Mathilde is a pain in the butt, and Cherice mentions this every chance she gets to anyone who'll listen. Mathilde is picky and spoiled and needy. She's good-hearted, sure, but she hates her precious routine disturbed.

Yet this same Mathilde Berteau has just told her to promise to take the dogs to her immaculate house. This is so sobering Cherice can hardly think what to say. "Well, I know you're worried now."

"Cherice. Promise me."

Cherice hears panic in Mathilde's voice. What can it hurt? she thinks. The bed in Mathilde's guest room is a lot more comfortable than hers. Also, if the power goes out—and Cherice has no doubt that it will—she'll have to go to Mathilde's the day after the storm anyhow, to clean out the refrigerator.

Mathilde is ahead of her. "Listen, Cherice, I need you to go. I need you to clean out the refrigerator when the power goes. Also, we have a gas stove and you don't. You can cook at my house. We still have those fish Tony caught a couple of weeks ago—they're going to go to waste if you're not there."

Cherice is humbled. Not about the fish offer—that's just like Mathilde, to offer something little when she wants something bigger. That's small potatoes. What gets to her is the refrigerator thing—if Mathilde tells her she needs her for something, she's bringing out the big guns. Mathilde's a master manipulator, and Cherice has seen her pull this one a million times—but not usually on her. Mathilde does it when all else fails, and her instincts are damn good—it's a lot easier to turn down a favor than to refuse to grant one. Cherice knows her employer like she knows Charles—better, maybe—but she still feels the pull of Mathilde's flimsy ruse.

"I'll clean your refrigerator, baby," Cherice says carefully. "Don't you worry about a thing."

"Cherice, goddamnit, I'm worried about you!"

And Cherice gives in. "I know you are, baby. And Charles and I appreciate it, we really do. Tell you what—we gon' do it. We gon' go over there. I promise." But she doesn't know if she can actually talk Charles into it.

He surprises her by agreeing readily as soon as she mentions the part about the dogs. "Why not?" he says. "We can sleep in Mathilde and Tony's big ol' bed and watch television till the power goes out. Drink a beer and have the dogs with us. Ain't like we have to drive to Mississippi or somethin'. And if the roof blows off, maybe we can save some of their stuff. That refrigerator ain't all she's got to worry about."

"We're not sleepin' in their bed, Charles. The damn guest room's like a palace, anyway—who you think you is?"

He laughs at her. "I know it, baby. Jus' tryin' to see how far I can push ya."

So that Sunday they pack two changes of clothes, plenty for two days, and put the mutts in their crates. The only other things they take are dog food and beer. They don't grab food for themselves because there's plenty over at Mathilde's, which they have to eat or it'll go bad.

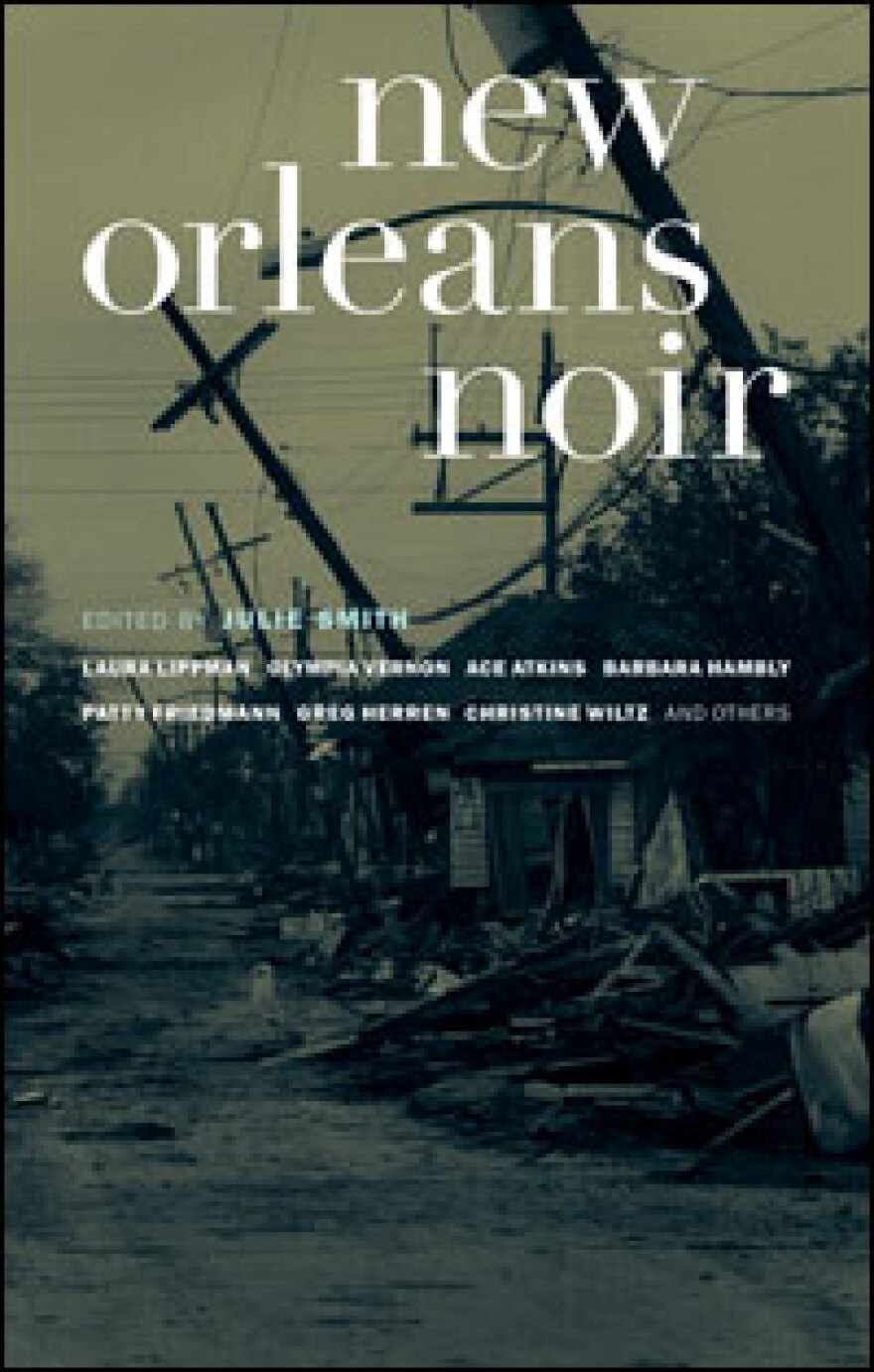

Excerpted from New Orleans Noir, edited by Julie Smith. Excerpted by permission of Akashic Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDM3NjYwMjA5MDE1MjA1MzQ1NDk1N2ZmZQ004))