I was having the time of my life. I was nineteen years old and had just completed my first year at Central Connecticut State College as an acting major. In the fall, I would transfer to NYU and begin studying with Stella Adler, the legendary acting teacher. And I was returning to the Goodspeed Opera House for my second year.

Goodspeed is a beautiful Victorian theater built in 1876 on the banks of the Connecticut River. It is dedicated to the American musical and is one of the country's best regional theaters. I had been there the year before as a technical apprentice—which means I had the privilege of working seventy hours a week for no money, but with the opportunity to be around professional actors, designers, directors, and stagehands. I had done community theater, I had done high school theater, I had even done a little college theater my first year, but nothing is the same as being around professionals. Shortly after I returned in the spring of 1976, I was promoted to a paid position, the first time anyone had gone from apprentice to staff member in the same season. I was proud of that.

Pride turned to concern when Michael Price, the executive producer, called me to his office. I had seen Michael around and he had always been friendly, but if I was being called to his office, I assumed I was in big trouble for something—and I couldn't figure out what. When I got there, he looked me in the eye and said, "How would you like your Equity card?" The Actors' Equity Association is the union that represents professional actors, but there's a catch-22 about joining: You can't be a professional actor in an Equity production unless you have your card—but you can't get your card until you do an Equity show. You have to have someone high up to sponsor you, and now Michael was offering to be my sponsor. Clearly he had recognized my acting ability from a few walk-ons and the way I moved scenery. All I had to do, he said, was find and train a dog for a new show without spending any money. I had never trained a dog before. I didn't know anything about training a performing dog. But in true show-business fashion, I immediately agreed.

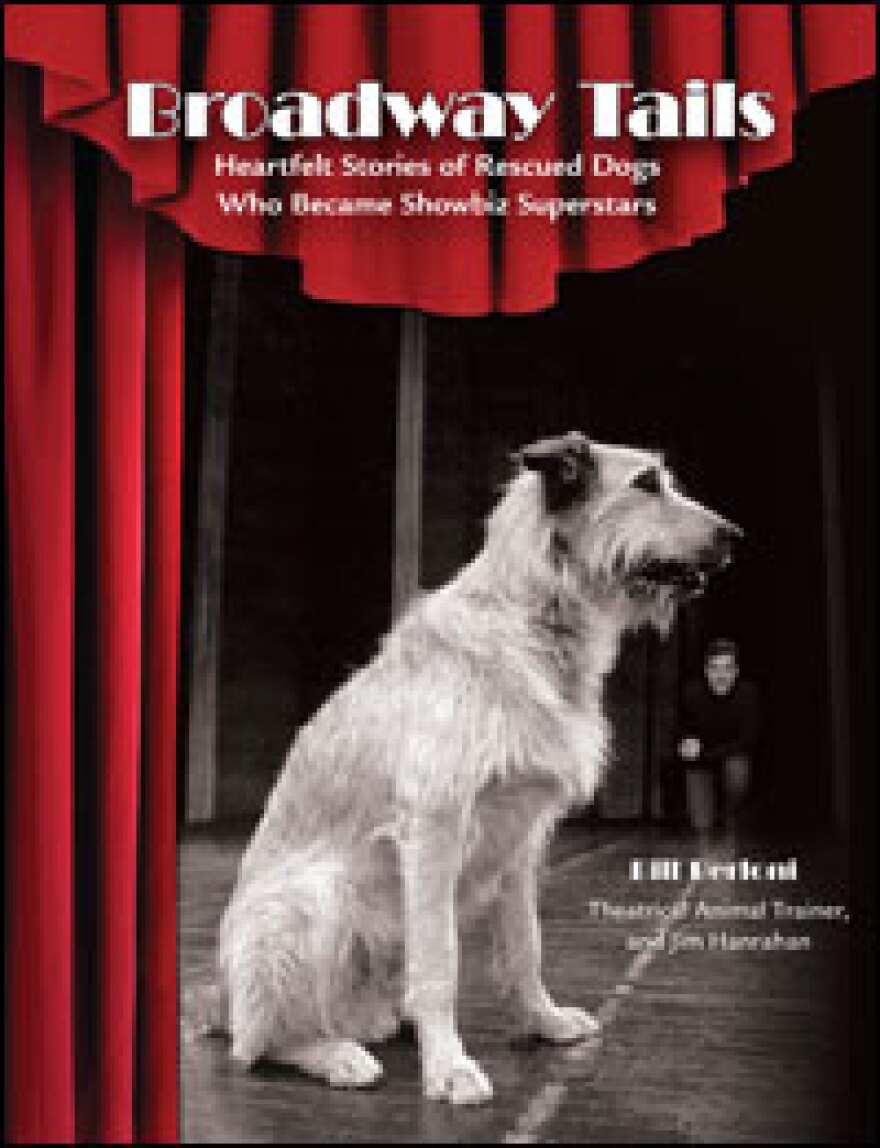

I left his office, went outside the building, and started jumping up and down with joy. I ran over to the shop and told everybody that I was going to be an actor. I went to the pay phone and called my mom and dad, I called my best friends, I called everybody I knew, telling them that I finally had my big break. But as I calmed down, I asked myself why I'd been given this important job. The answer was simple—no one else wanted it. The show we were going to do was called Annie, based on the classic comic strip, Little Orphan Annie. The dog, Sandy, was a major character, and no one thought you could train a dog to play a major character onstage. At the time, however, I was too naive to know that. After all, I had seen dogs play major parts in movies and on TV, so I didn't see why it couldn't be done for this show. What I didn't understand at that point was that what we see on screen is often the result of days of work, with multiple takes. Onstage, there would only be one chance to get it right—every night and in front of a live audience. It had never been done before.

Then there was the problem of the budget—or lack of one. No one would lend us a pet for the production, and buying a dog was out of the question. One of the crew suggested the best bet was to try the local dog pounds. So on Monday, my day off, I took the props department's Polaroid camera and beat-up green travel van and I went dog shopping.

If you remember the comic strip, Sandy didn't look like a real dog. He was a big red mutt with blank eyes, pointy ears, a white muzzle, and a big fluffy tail. The creators of the show knew we'd never find a real dog that looked like that, so I was told to get a medium-sized dog of sandy color and no distinguishable breed. Back in 1976, there weren't many animal shelters like the ones we know today, staffed by wonderful volunteers. In Connecticut at that time, most towns had dog pounds—generally a few pens or cages behind the town garage—where the local animal control officers kept strays. I went from town to town, walking out to look at two or three dogs at a time: skinny, shivering, huddling in the corner, or attacking the bars. I had never seen animals in conditions like these before. Sometimes I would show up and there would be nobody there, and I'd find the dogs with no food or water. As the day progressed and I didn't find any dogs that met our description, I became more and more disheartened. I made myself a promise—if I ever got a dog, I would rescue it from a shelter.

Late in the afternoon, I ended up at the Connecticut Humane Society, which was a shelter rather than a pound. If you found a stray or couldn't keep a pet, you could bring it there voluntarily. It looked like a jail—an old brick building with two long extensions that had twenty-five cement-and-chain-link runs on each side of a long hallway. Most of the pounds had no more than three or four dogs. The Connecticut Humane Society had a hundred. As I started walking past the cages, most dogs were jumping and barking, while some just cowered in the corner. The sound was deafening and the smell, overwhelming. I didn't see any dogs that matched our description, and I was getting more and more depressed. I almost left after going through the first wing, but something said, go down the other side.

The first time I saw him, he was sitting in the shadows, not barking or jumping. As I looked closer, I could see he was medium-sized, of no particular breed, and although his coat was wet and dirty, it was definitely a sandy color. When I stopped and knelt down, he slowly turned his head over his shoulder and looked at me with the biggest, saddest brown eyes I had ever seen. The card on the front of the cage said simply: 1½ YEARS OLD, MALE, STRAY, NO NAME. I got the attention of the attendant, and I asked him if I could bring the dog out. Over the racket, he yelled: "He's been pretty badly abused. He doesn't like people. I've got to get a rope to get him out."

He walked away, but I couldn't wait. I knelt again and opened the cage. I stuck out my hand and called, "It's okay, boy. Come here . . . come here." He looked at me with those sad eyes for what seemed like the longest time. Then he crept over to me, lay down on the floor, and let me pet him. I smiled and told him everything was going to be okay.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDM3NjYwMjA5MDE1MjA1MzQ1NDk1N2ZmZQ004))