Language Advisory: This excerpt contains language some readers may find offensive.

Chapter 1: Contact!

I first saw them on the slip road. They were trapped in the muddle of traffic, jostling to get through, eager, anxious, impatient; the mood of the driver transmitted down through the steering wheel and the throttle into the jerking, pushy movements of the car. I'd watched them as we drove past with that dawning of unease that comes from instinct, and now they were behind us, framed in my rearview mirror, kicking up a plume of road dust as they wove through the morning traffic on the highway through Fallujah. Pickups loaded with workers on the open backs, loose-fitting robes snapping in the milky warm slipstream, moved to let the black BMW 7 Series charge through. They were like members of a herd making way for a big predator that had earmarked its prey farther into the throng.

I knew what was coming now just as the herd, watching from their pickups and battered sedans, did. They simply watched the pursuit with relieved interest, glad not to be the one pursued and hoping, above all, not to be noticed. To be honest, I'd known what was coming from the moment I'd seen the BMW, with its blacked-out windows, stuck temporarily on the slip road. It was typical, too typical, of the vehicles used by gangs of insurgents in Iraq, and as they loomed up in my mirror, I knew with utter certainty that they were about to strike. But the difference was that I'm not one of the herd.

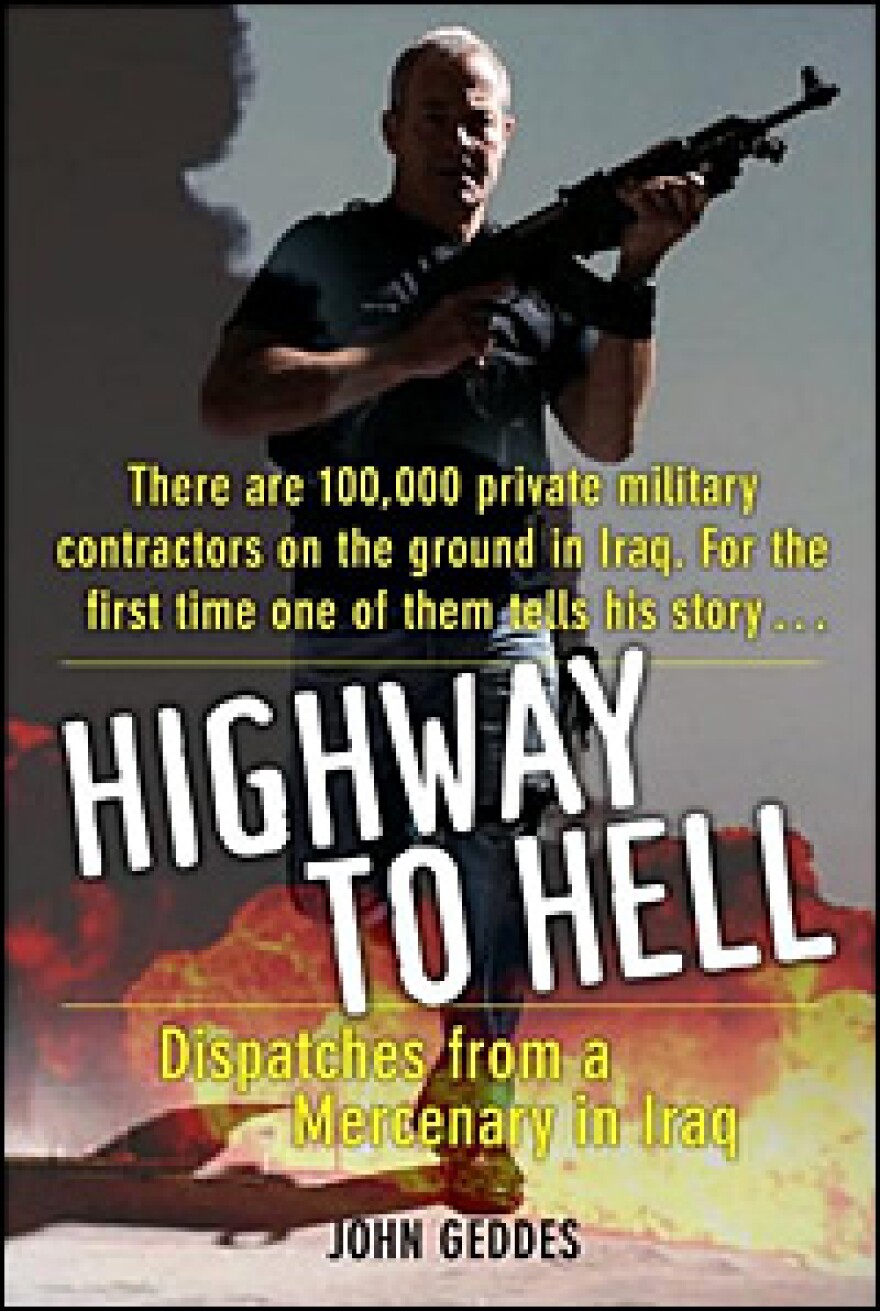

I used to be a warrant office in the British SAS and now I'm a soldier of fortune. I'm a hired gun, a mercenary if you like, and I'm the man who was trying to keep the other four guys in the car alive on the drive from Jordan to Baghdad along the most dangerous road in the world, down the Fallujah bypass and around the Ramadi Ring Road. It's a routine they call "the Highway to Hell."

There were four others in the car, a TV crew from a major UK network and a Jordanian driver, and as I watched that BMW gaining on us, all my senses combined to help me stay focused on keeping my clients and myself alive. I barely took my eyes off the mirror, leaving my peripheral senses to tell me if other predators had joined the chase, but as events unfolded, it was to be just us and them. Ahmed, my driver, had seen them, too, and I didn't have to tell him who they were. He started to mutter and jabber under his breath and I couldn't tell whether he was praying or cursing, only that he was terrified. He never usually perspired, but within seconds beads of sweat were running down his forehead and the side of his neck.

The BMW was cruising behind us, closely matching our speed, and that's always a real giveaway. They call it a "combat indicator" in the military, but I didn't need any indicators; I'd had a shit feeling about them ever since I spotted the BMW on the slip road.

Then they began moving up on us with evident hostile intent and I weighed in my hands the AK-47 lying in my lap for a moment before resting it back there again. I had my window open, but I closed it to hide behind its tinted glass. The BMW came up alongside us and the black window in the front came down like a theater curtain, revealing the driver and a guy who had the air of a man in charge sitting alongside him.

They cruised past us at a good speed, nice and steady, though, since they had nothing to worry about – it was their backyard, they were the top predator in the chain, and they were going to take their time. I guess they were thinking that maybe we were rich Iraqis or Kuwaitis, or that Japanese tourists would be nice – and yes, believe it or not, they do come sightseeing from Tokyo. The crew in the BMW would have loved the three-man Western crew on board – all that hostage money – and whatever happened, they'd have the camera kit and three satellite phones to sell. A real steal, and just for good measure, Ahmed would be slotted like a dog.

Ahmed kept on muttering under his breath, and they were still in no hurry to put him out of his suspense as I watched them come alongside us for the second time. Again they drew back behind us, only to spurt forward and come back alongside us yet again. Maybe they were enjoying their game of cat and mouse. The clients were sleeping off a hangover on the backseat. No need to wake them, I thought, nothing they can do about it.

Anyway, I had one advantage because our big GMC four-wheel-drive SUV gave me a view down onto the gunmen, and as I looked into the car, their back windows were lowered and I saw three armed men on the rear passenger seat. In the front, the driver was wearing a stick smile behind a shemag that had partly fallen away from his face; the guy alongside him had his shemag wrapped around his features as he leaned halfway across the driver to wave and gesticulate out of the window with his AK-47. I've got one of them, too, I was thinking, but I'm not showing it. His eyes were burning with hatred and disdain and he obviously wanted us to pull over, but I couldn't believe it when I felt us slow down as Ahmed, the man with the most to lose if you count his life, actually began to obey.

"Fucking drive, Ahmed," I snarled at him. His foot went down again and we temporarily spoiled the synchronized driving display of the scumbag in the 7 Series, but they were soon backing us. Ahmed was gibbering out loud in Arabic in a constant flow of verbalized terror as I looked through my tinted window at the four armed men in the car. Years of experience told me that their demeanor and the way they were holding their weapons meant that the last thing they were expecting was a real fight. They must have believed they had all the cards and that much sooner than later we'd be pulling over to the side of the road to deliver them their prize. I decided to keep my ace well hidden under the table, on my lap and out of sight.

They forged ahead again and the boss leaned across once more, but this tie he shoved the AK in front of the driver and out of the window and let a burst go across our hood to encourage us to pull over. I fought hard with any idea of dropping my window and lifting my AK off my lap and into sight. Ace under the table was my lifesaving mantra at that moment, ace under the table. I pushed everything else out of my mind but my sight of the gunmen and the thought of the ace I would play. I knew what I had to do, because the next time he fired, the burst would pour directly into our vehicle and that would be a very bad thing.

I stared through my tinted window across the three feet of door metal and swirling dusty air that separated us and I could clearly see that the scowling gunman next to the driver was trying to eye-ball me. I lowered my window as I looked back at him. I looked straight through him and then I did it. I played my ace, but even then I didn't lay it on the table. They never saw my cards. I just pressed my finger onto the trigger of the Kalashnikov still resting on my lap and let go a long burst of fire.

The familiar metallic clattering of an AK was indiscernible inside the car as it filled with the most terrible, deafening cacophony of sound. Clat! Clat! Clat! It seemed to go on and on, filling my world with an awful fanfare of destruction. Clat! Clat! Clat!

The armor-piercing assault rounds tore through our door and their door, too, in a microsecond, ripping metal and flesh without discrimination in the 7 Series. I watched the driver's head explode as the height difference of the two vehicles laid it on the line. The gunman next to him screamed, openmouthed in horror, all hatred and disdain wiped clean from his eyes by disbelief, as the assault rounds sliced into him, too, and tracked through his body.

CLAT! CLAT! CLAT! My finger still pressed the trigger and rounds kept tearing across that tiny three-foot space for another couple of seconds, until the BMW suddenly faded and fell back. I followed it in the mirror and saw steam and black smoke billowing from under the hood, so that I knew the end of my burst has smashed their engine block.

I watched the BMW start to fishtail and skid as our previously close contact became a surreal disconnection. We were still in traffic, but cars and trucks were now evaporating from the scene of the high-speed shoot-out with practiced ease. But my imperative wasn't traffic flow, and the critical thing was my certainty that the driver was dead and his boss was probably dead in the seat alongside him, too. As for the three gunmen behind them, they hadn't even had time to spit, let alone respond, and they were left impotent as the BMW spun out of control.

"Drive , fucking drive," I screamed at Ahmed, and he floored it as I turned to the correspondent and his crew, who were now sitting transfixed and deafened by sound and fury after the rudest awakening of their lives.

"Okay, guys?" I asked, barely able to hear my own voice. They nodded rigidly through the haze of acrid cordite that filled the car. I watched as their eyes kept wandering away from mine towards the gun still resting on my lap and then to the door alongside me and then back again. They were trying to work out why I hadn't fired through the window, why the door wasn't a mangled mess, just pierced by a series of neat holes marked out by flash burns. They were trying to work out why they were still alive.

"Welcome to Fallujah," I said, but they looked very pale and not another word was spoken until we reached Baghdad.

Our journey had begun at dawn that day when light welled-up over the city, still cooling from the heat of the day before like a giant concrete radiator, and the haunting wail of the call to prayer floated down from a mosque tower over downtown Amman.

That chant of the muezzin to the faithful, the clichéd soundtrack to every documentary ever made on the Middle East – you know exactly what to expect but it still gets to you every time and never fails to raise the hairs on the back of your neck. These days, it never fails to set me on edge. It's become the theme song for episodes of death and mayhem and starts the day with an unwelcome reminder that a religion founded on a philosophy or order and mutual respect has been twisted into an alibi for murder and bombing.

I'd already showered and shaved and my kit had been checked, rechecked and checked again; now it was ready to go, so there was nothing to do but get on with it. That constant checking of kit is an abiding theme in my life and it gets to be such a routine that I almost find myself looking into the mirror to check that I'm taking the right bloke on the job. I grabbed my small day sack with a survival kit in it, checked that I had my ID and passport, and then went downstairs to join the others in the hotel foyer.

The correspondent was seasoned, his cameraman an experienced guy who knew the ropes, and the soundman-cum-fixer was the third member of the crew. Ahmed was a veteran on the run.

I went through the drill with them. It always begins with the briefing – the "actions on" as the military call it – when I cover what they've got to do in the event of a road accident, an ambush or a hijack. I stood there feeling like cabin crew going through the pre-flight emergency drill while my clients, sprawled out on the hotel's leather sofas, looked just as bored as the average business passenger on a scheduled flight.

They smiled wanly when I get to the bit where I told them, "Remember, we don't stop at service areas; we piss on the side of the road. And we don't look at our dicks while we're doing it; we keep aware and look about us."

There were no women on that trip but it would have been just the same for them, with a biological variation of course, and the guys knew that I was serious when I told them, "There are service areas, but they're a no-no since a CNN crew stopped at one and got rumbled by insurgents. They were followed and a few rounds were fired through the back of the vehicle. The driver was killed and they were very lucky to get away."

It was time to go and they hauled themselves out of their seats and joined the pile of aluminum camera boxes stacked up under the front awning of the hotel, alongside the SUV.

"Hard cases up against the backseat, please," I told them, and the camera boxes were packed where they would afford at least some protection from any incoming rounds to our rear. The soft luggage – rucksacks and hold-alls full of clothing – were piled in front of the hard boxes.

While the kit was being packed the correspondent paced nervously up and down as though he was rehearsing a piece to film. He'd been up drinking with the cameraman into the early hours and all they wanted to do was to get into the vehicle and go to sleep.

Meanwhile, Ahmed dragged on a foul-smelling cigarette, and I placed myself upwind of him, carefully watching the unfolding scene as the rising sun glinted off my mirrored shades. He's a nice guy, Ahmed, a family man who knows only too well that captured Jordanian drivers are always killed by insurgents. Why? Because they're not worth a bean on the hostage market, and anyway, they've betrayed Islam by chauffeuring the infidel invaders. Like all the Jordanians who daily risk their lives on the Baghdad run, Ahmed's either very broke or very brave, or, I suspect, probably both.

I pointed towards the hood of the SUV and he lifted it so that I could personally check the oil and the radiator levels. I even checked the windshield wash. Check and recheck – its attention to detail that keeps you alive. I glanced at the tires, too, just to make sure they had some tread on them; then Ahmed turned the key in the ignition and I watched the needle on the fuel gauge rise to full.

"Thanks," I told him, "You happy with everything?" Ahmed smiled in reply and I turned to the TV crew. "All aboard, guys, time to roll. Just make sure you've got everything you need."

It takes three hours to get to the Iraqi border, and there wasn't a great deal of chat in the car once they'd discussed some details of their arrangements, whom they'd be meeting, and the first story they hoped to get in the can. The correspondent and the cameraman were obviously desperate to get some sleep and they soon nodded-off, heads occasionally lolling from side to side with the unsynchronized rhythm of the car. It wasn't long before the sound man joined them.

That first leg of the journey is always unrelentingly boring, with mile after mile of yellowy gray rock and sand, and I knew that we wouldn't see a scrap of vegetation until we got to Iraq. The difference is quite dramatic then because the civil service mandarin in Britain who drew the lines on the map, laying out the boundaries of the two countries nearly a century ago, gave the Jordanians the short straw. They got a lunar landscape with not a drop of oil beneath is, while the Iraqis got two river and a bit of greenery sitting on top of a gigantic oil well.

I spotted Iraq as that change in landscape came into view, just before I spotted the border post itself, a nondescript collection or buildings with a small U.S. Army stockade standing at arm's length from the local administration. It's a sight that galvanized me and pulled out of the wheel-drumming monotony of the last three hours, and I knew that the mood over the next couple of hours would be very different.

The Jordanian checkpoint is always a flurry of activity—visas being stamped, waiting in a queue of fifty, and, of course, the obligatory payment to preclude any more border bureaucracy. The Iraqi border patrol just waves us through most of the time, only occasionally looking at credentials, but there's never a lot of fuss.

We soon pulled-up outside of the U.S. guardhouse for the really important part of the proceedings. "You guys put your flak jackets on while I collect my tool," I told them, and then I vanished into the guardhouse.

When I first arrived in Iraq, I learned that a lot of the security teams bury their weapons in caches on the Iraqi side, take a GPS bearing on the spot, and just dig them up when they cross back over the frontier on their next run in. well, I didn't like the sound of it at all. What if there's a pair of unsympathetic eyes out there watching you as you make your cache? You might just find yourself digging into a booby trap or walking onto a small antipersonnel mine that's been laid as a welcome mat by insurgents.

No, I didn't think that was the way for me, so I pondered the problem for a while, until my natural affection and admiration for the Americans and their way of doing business led me to a direct approach. I visited the U.S. border detachment on my first run and spoke to the big Louisiana-born master sergeant in charge.

"Do you know those Westerns where the sheriff takes the weapons off the cowboys when they arrive in town?" I asked him when the introductions were over.

"Sure do," he said.

"Well, I'm not a cowboy and you're not the sheriff, but I was wondering if you could do the same sort of thing for me, but in reverse, and take my guns when I leave town, so to speak, and go back to Jordan?"

"Why, hell yes, it'd be our pleasure," he told me, and that's the way it panned out. I just handed them in and got a receipt and they locked tem up until I returned. No fear of land mines or a nasty ambush, no sweaty digging in the scrub. In fact, no burial party of any sort at all.

There was another key benefit to this more civilized transaction, and that was the chance to chat with the Yanks in the guardhouse and any intelligence on insurgent activity that might have come back down the line to them. There were very few problems close to the Jordanian border, but the guys in the guardhouse always knew about anything going on farther up the road and they always like to shoot the breeze and gossip with people passing through—and information can mean survival in Iraq.

The master sergeant and I sealed the deal that day with a case of bear, which the yanks always grateful to receive, as the poor suckers fight in a dry army, and I showed them a couple of special-range drills with an AK. They were pleased, and I was happy to leave an infantry unit of the U.S. army with a little bit of SAS polish on its troops.

So it was that I stepped into the guardhouse handed over my gun chit, then waited for my weapons to be brought out from the Amory and handed to me.

"Here you go, sir," the young GI said, counting out my private arsenal, "One AK 47, serial number—"

"No need for the number, thanks. I'm sure it's the right one."

"Sure thing, sir. So that's one AK 47 assault rifle, plus six thirty-round mags; one Glock pistol, plus four twelve-round mags. Serial number?" He looked up inquiringly.

"No thanks."

"Okay, so here we go. Two NS. L2 grenades and one white phos' grenade. That's everything, sir, so if you can just sign here, you can take your weapons. Anything else I can help you with, sir?"

"Not really. Thanks very much." I scrawl my name across the bottom of the shit.

"Nothing going on up the road, is there?"

"All quiet, as far as we know, sir. Now you-all have a safe journey."

"Thanks, old son. See you on the way back."

I transferred the weapons into the vehicle, where the crew studiously avoided mentioning them at all because officially, as far as they were concerned, the guns, let alone the grenades, were not supposed to exist. You see, the problem about looking after a TV crews tend to begin with their network's policy on war coverage. The British and the other European media mostly work on the principle that once weapons are involved, journalistic impartiality and neutrality are lost and their crews will then be open to hostage taking and the unthinkable possibility of execution.

Paradoxically, it's argued, the absence of weapons will protect correspondents and crews from those fates as they tangibly demonstrate their noncombatant status. If only. You can be fairly sure that people like the infamous Musab al-Zaraqwai, who was Al Qaeda's man in Iraq at the time, hadn't taken the time to read the network editorial handbooks, but their actions spell out clearly any views they may have on the issues. It's quite simple. The word neutrality does not exist in their dictionary and all that matter to them is their own twisted interpretation of the word of the Almighty embodied in the Holy Koran. That boils down to a rule-of-thumb judgment that absolutely no one at all is offered safe passage through their hands, which in itself goes against the deeply ingrained traditions of hospitality in the Arab world. Rather, you're more likely to be exploited for you propaganda value on a few pleading video appeals, then have you hear chopped off.

The U.S. networks have been quick to recognize the realities in the region and tend to have a robust "balls to neutrality" policy and travel with more than enough firepower to take on the average game of insurgents. No one can legislate for sniper shots or a lucky hit with a rocket-propelled grenade and no one can insulate himself against a suicide bomber intent on hell, but if less than the worst happens, they reckon they have enough in reserve to protect and maintain the convoy until help arrives. There are certainly arguments for and against their strategy, which you might characterize as heavy-handed, but there are absolutely no sane arguments around Iraq without any weapons at all. None.

Anyway, I'd already had a free and frank exchange of views with my clients about the issues and told them that they could certainly instruct me that they didn't want me to carry a weapon. I, on the other hand, would ignore their instruction and would be carrying a weapon unless they absolutely did not want me to, in which case they'd have to find someone else. Therein, of course, lies their dilemma, because finding someone willing to drive the Highway without a weapon is a bit like looking for a free beer in a brothel. Like quite a few others on the security circuit out there, I had been persuaded to drive along the Highway unarmed on a score or more of occasions, but the number of close shaves I had left me feeling like Kojak and I resolved to travel armed or not at all. If people didn't like it, they didn't have to travel with me.

"Look," I told the correspondent, "just tell the news desk that you're traveling with a bodyguard who has been told not to carry a weapon. When you've done that, just pretend you haven't seen the weapon I'm carrying. It's simple. You didn't see it so if we end up in a shoot-out, then I'm the one to blame."

"That's all very well, John, but I could get the sack for traveling with an armed bodyguard," he replied.

"Of course you could and that would be terrible, but you could just as easily get yourself dead if I don't carry a weapon. Besides, the only way your bosses will find out that the rules have been broken is if we get captured at which point it won't matter anyway."

"What you say is all very well, John, but what if – "

"No what-ifs mate. I'll tell you what. If a band of insurgents decides to take us hostage because I'm carrying a weapon, it will be because I haven't used the weapon. Therefore if we are taken then, either way, it's my fault, so you can sack me before they sack you. In the meantime, pretend I'm the man with the invisible gun. Agreed?"

"Okay, but – "

"No buts. Deal?"

"Deal."

That's the way it went, yet I know full well that he could still face the sack today if his highly scrupled news desk, who were sitting safely back in the London studio at the time, found out that he'd broken their standing orders on war coverage. Crazy.

Well, the deal was done and I had sealed it by retrieving my weapons from the U.S. armory, so I went back to organizing the trip. They'd put on their body armor, the bulky type you commonly see worn on TV reports, which provides maximum protection but are crap for moving about in. I use my own high spec "restricted entry" body armor, designed for fighting in tight spots which is very expensive but, in the words of the brochure, an effective compromise between total protection and mobility. Don't know about that, but I certainly feel more comfortable in one.

The mood had shifted up a couple of gears in the car by then and there was a tangible sense of increased tension, even though it would be another hour and a half before the really high voltage ride began through Fallujah and Ramadi, and the start of the roller coaster is the point known as Feature 127.

It's just a stone way mark on the side of the road in the middle of nowhere, erected to tell the weary traveler that there are 127 kilometers to go to reach Baghdad, but it has taken on great significance for those who ride the Highway. That's because for some reason nothing ever seems to happen on the western side of Feature 127 and all hell can, and often does, break loose on the other side of it. Now it's a recognized rendezvous point and a place to stop, consider and compose oneself before the roller coaster begins.

I spotted the landscape around 127 before we reached the way mark itself and I told Ahmed to pull-in for a pit-stop before we go on. There were a couple of reasons for that, and first I remind everyone on board to have that "heads-up" piss before we continue, because there'll be no stopping on the road from then on unless we're absolutely forced to pull up. The correspondent yawned and looked a bit fed-up at being woken from a sleep that might have left him untroubled by the stresses and dangers of the Highway until he arrived at his hotel in Baghdad.

Unscrewing a bottle of water, I took a swig, then I set about arranging the cabin space for the rest of the run. At the same time, I was tuning myself up mentally for whatever may come with a routine that clearly signals a watershed in the journey and the need for a new, more focused mind set.

"Right, fellas, get your helmets on and keep them on for the rest of the trip, please. If there's anything you want out of your kit, get it now, if you would, and please don't mention it to me once we've set off again. I won't be interested. Whatever it is."

They strapped their helmets on and I looked at them carefully. They all had that same expression of incipient fear, just like someone who's going to go on a very big roller coaster. Their eyes were flat, almost glazed by a sheen of adrenaline waiting to be used. They didn't want to do it, but they were going to do it anyway, and they became increasingly aware of the thumping of their hearts and the dryness in their mouths as they fought the demons within to remain outwardly composed.

Ahmed fingered his worry beads and unconsciously chewed on his lip as he waited anxiously to take the wheel again. I was busy hanging spare body armor onto the door furniture inside the car to make an effective and proven barrier between the passengers and small arms fire. It's a precaution that has saved many lives. The check reflex kicked in again and I checked the oil, water, and the fuel. Just in case. When we were all loaded up, I cradled the AK in my lap covering it with my green and black shemag head dress, to hide it from any prying eyes and I handed Ahmed the Glock pistol, knowing he could use it because I'd shown him how. He stuffed it between his leg and the seat and nodded to me.

"Let's roll," I said, and Ahmed did just that, speeding down the road as if he were trying to lift a jet off a runway. He'll push the thing like that all the way to Baghdad, keeping the speedometer at a 100, as if a cart-full of demons were tailing him, and perhaps they were.

The traffic began to thicken a little as we approached Fallujah, a town that straddles the Highway like a piece of malevolent lagging, bombed, battered and shot up but largely unyielding, and that's when I spotted them jostling to find a way through the constipated traffic on the slip road. And then the black BMW 7 Series was framed in the rearview mirror as it charged up behind us.

Excerpted from HIGHWAY TO HELL by John Geddes © 2008 by John Geddes and Alun Rees. Reprinted by permission of Broadway Books, a division of the Doubleday Publishing Group.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDM3NjYwMjA5MDE1MjA1MzQ1NDk1N2ZmZQ004))