Language Advisory: This excerpt contains language some readers may find offensive.

Chapter One

LAND OF THE FAKE

The casket was wrapped in an American flag, bright in the sun reflected off the marble Tomb of the Unknowns at Arlington National Cemetery on a May morning in 1998. A military band played the old hymn "Going Home" as an honor guard lifted the casket and carried it to the waiting hearse. During the night, the coffin had been taken out from under the heavy stones of the tomb. It had rested there since Memorial Day 1984 when President Ronald Reagan led a ceremony to finally honor the soldiers of the Vietnam War by putting one of their own into the Tomb of the Unknowns. Who was he? What was his story? Where was his family? "We will never know the answers to those questions about his life," Reagan said that day. For fourteen years that casket protected an unknown soldier from the Vietnam War, guarded around the clock by the Army's Old Guard at the country's most solemn war memorial. On May 14, 1998, the disinterred casket was loaded into a black hearse and taken away.

Everyone at the ceremony that day knew that the human remains under the flag were not unknown. They were the remains of Air Force 1st Lt. Michael Joseph Blassie, who was shot down over An Loc on May 11, 1972. Jean Blassie, Michael's mother, knew it, as did his brother and his sisters, who watched from the steps above the tomb. I knew it, as I watched from a press stand.

Astonishingly, Pentagon officials knew it back in 1984.

I remember the moment during the ceremony when I realized the Tomb of the Unknowns was literally a fake on a monumental scale. A deliberate fake. A false monument.

The hearse drove away to take the remains to a laboratory for DNA testing. On June 30, the Pentagon announced that the Vietnam War remains in the Tomb of the Unknowns were officially not unknown anymore. They were the remains of Jean Blassie's son, Michael. Two weeks later, Michael Blassie was buried for good near the family's home outside St. Louis. "My brother deserves to be known," Blassie's younger brother, George, said that day.

I had been working on this story for months with two colleagues from CBS News, correspondent Eric Engberg and Vince Gonzales, a tenacious reporter who had unlocked the key secrets of the tomb. A series of stories we produced for The CBS Evening News had shown beyond any doubt that it was Michael Blassie, not an unknown soldier, in the tomb. The Reagan administration had been under tremendous pressure in 1984 to honor the most poorly treated soldiers in American history, the veterans of the Vietnam War. But technology had gotten so sophisticated that there simply weren't many remains from that war that hadn't been identified. Still, the pressure went down the bureaucratic food chain to the military identification laboratory in Hawaii. The Pentagon brass wanted unidentified remains to be buried at a presidential ceremony at the Tomb of the Unknowns on Memorial Day, and they intended to get them. One of the few sets of possible remains at the Hawaii lab had been labeled X-26. Those bits of human bone, however, had been clearly identified back in Vietnam as Michael Blassie's. Blassie was shot down during a daytime bombing run on North Vietnamese artillery positions that were pulverizing South Vietnamese troops and a handful of U.S. advisers at a place called An Loc. That night, Col. William Parnell sent out a patrol. They found bodily remains, Blassie's ID card, and other personal gear. Through some later screwup, the remains were separated from the identification card and eventually given the X-26 reference. But there was a clear paper trail. Witnesses were available to clear up any confusion. Military officials knew all of that when they sent the X-26 remains off to Arlington National Cemetery in 1984.

Our reports forced the Pentagon to reopen the case and exhume the remains. There is no soldier from the Vietnam War within the tomb today. But for years that monument was defaced by a fraud. It was another casualty of Vietnam. The memorial was insulted by the kind of stagecraft that the Reagan administration brought to Washington and that has flourished ever since. For me, it was an initiation into the land of the fake.

After the disinterment ceremony, I became even more of a phoniness vigilante than I had been. I have no special claim on authenticity or sincerity. But I'm fairly well trained to spot fakery and fraud in the public realm. My job back in 1998 was to produce a segment called "Reality Check" for The CBS Evening News. I was a professional bullshit hunter, and in those days Washington was loaded with big game. That was the year of the president and the intern--that woman, Ms. Lewinsky. President Bill Clinton was put through an impeachment trial essentially for philandering and some of his most zealous and righteous prosecutors were exposed as cheaters as well--Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich; his designated replacement, Bob Livingstone of Louisiana; and two powerful Republican committee heads, Henry Hyde of Illinois and Daniel Burton of Indiana. The hypocrisy rose to trophy levels. The hunting was easy.

Trust and confidence in government sank to Watergate-era lows. Wise people worried that "civility" had vanished from public life and that government was in perpetual "gridlock." Two commissions of academics and statesmen convened to ponder the civility crisis, the Council on Civil Society and the National Commission on Civic Renewal, and both issued dire reports.

Unfortunately, civility can't be commissioned, morality can't be legislated, and money can't buy you love. Despite levels of peace and material abundance on a scale this nation had never before seen, the mood grew even more sour. The election of 2000 between Vice President Al Gore and Texas governor George W. Bush was bitter and venal. But it was nothing compared to the battle that erupted after the disputed results in Florida. The conventional uber-narrative of American politics then (and now) was the story of polarization, red versus blue, right against left. But it seemed clear to me that this wasn't anything like the extreme, violent polarization of the Civil War, Prohibition, or the 1960s. This was very different and didn't run nearly so deep. Soon after the 2000 election, columnist Lars-Erik Nelson died. A tribute quoted him as once saying, "The enemy isn't liberalism. The enemy isn't conservatism. The enemy is bullshit." I immediately cut it out and taped it to my desk. I was in the trenches of the bullshit wars. I even had a motto.

"One of the biggest reasons I left Elkton Hills was because I was surrounded by phonies," said J. D. Salinger's Holden Caulfield, the greatest enemy of phonies of all. I felt like a grown-up Holden, surrounded by phonies, and it felt crummy, as he would say. In the very last month of the twentieth century, I changed jobs and went to work on the Internet, as an editor for CBSNews.com. The dot-com bubble burst a few months later. Terrific timing on my part.

Do We Hate Us?

Part of my new job meant regular travel between Washington, D.C., where I live, and New York City, where Satan lives. One Tuesday a few months after the Battle of Florida ended, I was headed to a 9:30 a.m. Delta shuttle at Reagan National Airport. The lawyers, investment bankers, lobbyists, and media types like me who are shuttle regulars lined up as usual about a half hour before the flight, barely looking up from our PalmPilots and Wall Street Journals. As the first passengers entered the ramp to the plane, the gate agents turned them around and said there was a delay at LaGuardia Airport in New York. Someone on a cell phone said they heard that a small plane had crashed into the World Trade Center. I called my newsroom and they confirmed that something had happened but didn't know much more. It was about 9:15 by then and the gate agent said all the New York airports were closed.

I ran to my car parked in the nearby short-term lot. It was past 9:30 when I pulled onto the George Washington Memorial Parkway along the Potomac River, listening to radio reports that the planes that hit the World Trade Center appeared to be commercial airliners. I tried to get the newsroom back on my cell phone. As I drove near the Pentagon from the southeast, I saw a mass of dark smoke rise up from behind the building.

After 9/11, the whole bullshit-detection business seemed trivial. A good deal of the news I had covered over the years and many of the stories I had worked so hard on now struck me as frivolous. The entire country felt like it had been naive and immature. Americans were stunned and disoriented; the terrorism they watched stalking foreign lands on television had come to their own country, bringing real blood and real death. A few weeks after 9/11, Newsweek magazine set out to answer an essential question with a cover story headlined "Why They Hate Us."

"Everything has changed" was a common platitude at that time. But of course everything hadn't changed.

Certainly politics had not changed. A little more than a year later, the debate in the Senate over granting the president authority to invade Iraq smelled more of posturing than statesmanship. A year after the invasion of Iraq, polarization was again the Big Idea that pundits used when describing the country. Civic distemper was back, with the exaggeration and animosity common to fresh disenchantment. An unpopular war, a corporate crime wave, and an economy that was great for the rich and hard for the rest combined to put the country in a foul humor. Revelations about sexual abuse by Catholic priests spread disillusionment and cynicism; was there no corner of society left that we could look at with innocence and uncomplicated respect? The attention we lavished on American Idol, Lindsay Lohan, and Anna Nicole Smith proved we could be every bit as superficial as we were before some 2,700 Americans were murdered in a single day. But there was something new: a sense of civic embarrassment bordering on shame. The sort of phoniness discovered at the Tomb of the Unknowns was rampant and alienating, but it was a subset of something much bigger. Americans were down on themselves, and for good reason, it seemed. We needed a new cover story to explain this new condition. We needed to figure out why we hate us.

"National pride," the philosopher Richard Rorty wrote in Achieving Our Country, "is to countries what self-respect is to individuals: a necessary condition of self-improvement." Our lack of national pride--our lack of social self-respect--makes all society's problems harder to solve.

What We Hate

The "hate" we need to understand is not the bomb-throwing kind of hate. It's not the diseased paranoia of Timothy McVeigh, the Weather Underground, or the Unabomber. It is a mood of social self-loathing. The country is suffering from low self-esteem and is acting out. Everybody doesn't hate everything. We don't hate one another in the flesh. Often we hate abstractly. But from little things to big, everyone hates something.

My friend Mo hated it when a young man at the table next to him at a coffee shop clipped his fingernails. He hated it more when the kid was oblivious to the dirty looks Mo sent his way. Mo was livid when he explained to the guy that sending shards of dead protein and cuticle around a place where people eat food is impolite and unappetizing and was met with a blank slacker stare that was the nonverbal equivalent of "Fuck you." Snip.

My brother didn't like it when an angry cow kicked him in the back and cracked several vertebrae. But he also didn't like it when he was watching CNN while recovering in a rural hospital in central Missouri and a nurse looked up at a news story about gay marriage and said it was a sign that Satan was sending America straight to hell. And I imagine the nurse hated that there were gay people on the news and that they wanted to get married. "Worlds collide," in the words of Seinfeld's George Costanza.

My sister hated hearing the story of a man who didn't want his kid to go to camp with a bunch of other rich kids so he paid a "lifestyle management consultant" $15,000 to find an appropriately downscale summer camp that cost $5,000.

My colleague Danny hated it when a girl sitting next to him on the subway attached her false eyelashes and Q-tipped her waxy ears. My wife doesn't like seeing Bentleys on the road. She went on Google and discovered most Bentleys cost over $300,000.

My friend Jeff was grumpy when he had to call Verizon to report a problem and found himself talking to a computerized voice. But he got really angry when the voice, having determined that Jeff had an actual problem, said, "I am sorry to hear that." How could "you" be sorry to hear that? "You" are not a person but a machine. How absurd, how insulting, to be forced to pretend to be having a human interaction with a machine. What was Jeff supposed to say? "And I'm sorry that you are just a machine because you seem so sensitive"?

I don't like people who go to the Holocaust Memorial Museum wearing T-shirts that say "Eat Me." True story.

When you write an Internet column about things like this, as I do, and your e-mail address is at the bottom of every column, as mine is, you hear about what people hate loud and clear, over and over. I can report definitively that people hate columnists who hate things. They loathe snails who drive slowly in the left lane. They don't like people who talk full volume about the heartbreak of their psoriasis on cell phone headsets in restaurants and quiet bookstores. They don't like that more and more stores are chains, the same everywhere, mostly with lousy service from blase employees, even if prices are lower and choice is more plentiful. They hate it when big multinational corporations have advertisements that say "We care about you," because corporations can't care, and besides, they don't really know you that well. They don't like it when they're talking with someone who starts thumbing their little digital personal device to answer an e-mail from someone five hundred miles away. They don't appreciate being bumped into at airports or on sidewalks by people with white earbuds crammed in their ears, oblivious to their human surroundings. They don't like oversold flights.

I don't care for Marilyn A. Mitchell. I haven't actually met her, but she's a "personal coach" who sent me literature promising "a refreshing way to look at making necessary changes in your life." I didn't even know I had to make changes. She told me to "Make changes that will nourish your desire, spark your enthusiasm, provide sensitivity to realize your true gifts." Actually, I hate her--sensitively, though. I'm pretty sure I don't have any true gifts.

These are little things in some respects. They're not global warming or genocide. But they don't feel little. They cramp up everyday life. Is this happening more than at other times in history? I have a thick file of polls that indeed say most people do think America is ruder, more vulgar, and more inconsiderate than it used to be. But people almost always think things used to be better and are getting worse. What is important is that these kinds of irritations are shared by virtually every person I have encountered in the past several years. The big song in Avenue Q, a popular Broadway musical, is called "It Sucks to Be Me." We can be whiny, too.

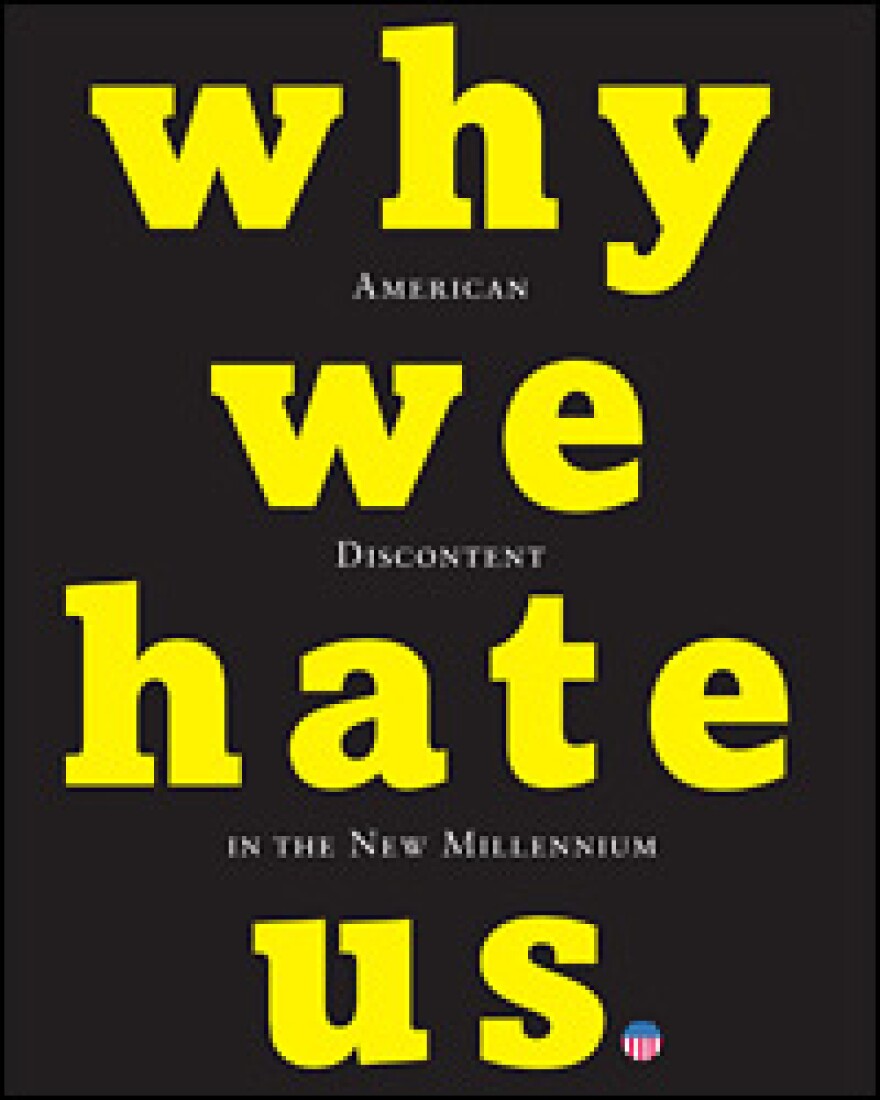

Excerpted from Why We Hate Us by Dick Meyer Copyright © 2008 by Dick Meyer. Excerpted by permission of Crown, a division of Random House, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDM3NjYwMjA5MDE1MjA1MzQ1NDk1N2ZmZQ004))