There's a joke interrogators like to tell: "What's the difference between a 'gator and a used car salesman?" Answer: "A 'gator has to abide by the Geneva Conventions."

We 'gators don't hawk Chevys; we sell hope to prisoners and find targets for shooters. Today, my group of 'gators arrives in Iraq at a time when our country is searching for a better way to conduct sales.

After 9/11, military interrogators focused on two techniques: fear and control. The Army trained their 'gators to confront and dominate prisoners. This led down the disastrous path to the Abu Ghraib scandal. At Guantanamo Bay, the early interrogators not only abused the detainees, they tried to belittle their religious beliefs. I'd heard stories from a friend who had been there that some of the 'gators even tried to convert prisoners to Christianity.

These approaches rarely yielded results. When the media got wind of what those 'gators were doing, our disgrace was detailed on every news broadcast and front page from New York to Islamabad.

Things are about to change. Traveling inside the bowels of an Air Force C-130 transport, my group is among the first to bring a new approach to interrogating detainees. Respect, rapport, hope, cunning, and deception are our tools. The old ones — fear and control — are as obsolete as the buggy whip. Unfortunately, not everyone embraces change.

The C-130 sweeps low over mile after mile of nothingness. Sand dunes, flats, red-orange to the horizon are all I can see through my porthole window in the rear of our four-engine ride. It is as desolate as it was in biblical times. Two millenia later, little has changed but the methods with which we kill.

"Never thought I'd be back here again," I remark to my seatmate, Ann. She's a noncommissioned officer (NCO) in her early thirties, a tough competitor and an athlete on the air force volleyball team.

She passes me a handful of M&M's. We've been swapping snacks all through the flight. "When were you here?" she asks, peering out at the desertscape below. Her long blonde hair peeks out from under her Kevlar helmet.

"Three years ago. April of o-three," I reply.

That was a wild ride. I'd been stationed in Saudi Arabia as a counterintelligence agent. A one-day assignment had sent me north to Baghdad, shivering in the back of another C-130 Hercules.

Below us today the southern Iraqi desert looks calm. Nothing moves; the small towns we pass over appear empty. In 2003 it was a different story. We flew in at night, and I watched the remnants of the war go by from 200 feet, a set of night-vision goggles strapped to my head. Tracer bullets and triple A (antiaircraft artillery) arced out of the dark ground past our aircraft, our pilot banking the Herc hard to avoid the barrages. Most of the way north, the night was laced with fire. Yet when we landed at Baghdad International, we found the place eerie and quiet. Burned-out tanks and armored vehicles lay broken around the perimeter. I later found out they'd been destroyed by marauding A-10 Warthogs.

On this return flight, we face no opposition. The pilots fly low and smooth. The cargo section of these C-130 's is always cold. I pop the M&M's into my mouth and fold my arms across my chest. The engines beat a steady cadence as the C-130 shivers and bucks. Ann puts her iPod's buds in her ears and closes her eyes. Next to her, I start to doze.

An hour later, I wake up. A quick check out of the porthole reveals the sprawl of Baghdad below. We cross the Tigris River, and I see one of Saddam's former palaces that I'd seen in '03.

"We're getting close," I say to Ann.

She removes her earbuds.

"What?" she asks.

Mike, another agent in my group, leans in from across the aisle to join our conversation. He offers me beef jerky, and I take a piece.

"We're getting close," I repeat myself.

We reach our destination, a base north of Baghdad. The C-130 swings into the pattern and within minutes, the pilots paint the big transport onto the runway. We taxi for a little while, then swing into a parking space. The pilots cut the engines. The ramp behind us drops, and I see several enlisted men step inside the bird to grab our bags. Each of us brought five duffels plus our gun cases. When we walk, we look like two-legged baggage carts.

"Welcome to the war," somebody says behind me.

After hours of those big turboprops churning away, all is quiet. We descend from the side door just aft of the cockpit. As we hit the tarmac, a bus drives up. A female civilian contractor jumps out and says, "Okay, load up!"

Just as I find a seat on the bus I hear a dull thump, like somebody's just slammed a door in a nearby building —

except there aren't any nearby buildings.

A siren starts to wail.

"Oh my God!" screams our driver. "Mortars!"

She stands up from behind the wheel and dives for the nearly closed door, where she promptly gets stuck. Half-in, half-out of the bus she screams, "Mortars! Mortars!"

We look on with wry smiles.

Another dull thud echoes in the distance. The driver flies into a panic. "Get to the bunkers now! Bunkers! Move!" She finally extricates herself from the door and I see her running at high speed down the tarmac.

"Shall we?" I ask Ann.

"Better than waiting for her to come back."

We get off the bus and lope after our driver. We watch her head into a long concrete shelter and we follow and duck inside behind her. It is pitch black.

Another thump. This one seems closer. The ground shakes a little.

It is very dark in here. The bunker is more like a long, U-shaped tunnel. I can't help but think about bugs and spiders. This would be their Graceland.

"Watch out for camel spiders," I say to Ann. She's still next to me.

"What's a camel spider?" she asks.

"A big, aggressive desert spider," says a nearby voice. I can't see who said that, but I recognize the voice. It is Mike, our Cajun. Back home he's a lawyer and a former police sniper. He's a fit thirty-year-old civilian agent obsessed with tactical gear.

"How big?" Ann asks dubiously. She's not sure if we're pulling her leg. We're not.

"About as big as your hand," I say.

"I hear they can jump three feet high," says Steve. He's

a thirty-year-old NCO and another agent in our group of

Air Force investigators-turned-interrogators. This tall, buzz-cut adrenaline junkie from the Midwest likes racing funny cars in his spare time. In the States, his cockiness was suspect. Out here, I wonder if it won't be exactly what we need.

"Seriously?" Ann asks.

Thump! The bunker shivers. Another mortar has landed. This one even closer.

"I'm still more worried about the spiders," Mike says.

I have visions of a camel spider scuttling across my boot. I look down, but it's so dark that I can't even see my feet.

The all-clear signal sounds. We file out of the bunker and make our way back to the bus. The driver tails us, looking haggard and embarrassed. Her panic attack cost her whatever respect we could have for her. We climb aboard her bus and she takes us to our next stop.

We "inprocess," waiting in line for the admin types to stamp our paperwork. We have no idea what's taking them so long. Hurry up. Wait. Hurry up. Wait. It's the rhythm of the military.

Steve finishes first and walks over to us. "Hey, one of the admin guys just told me a mortar round landed right around the corner and killed a soldier."

The news is like cold water. Any thought of complaining about the wait dies on our tongues. We'd been cavalier about the attack. Now it seems real.

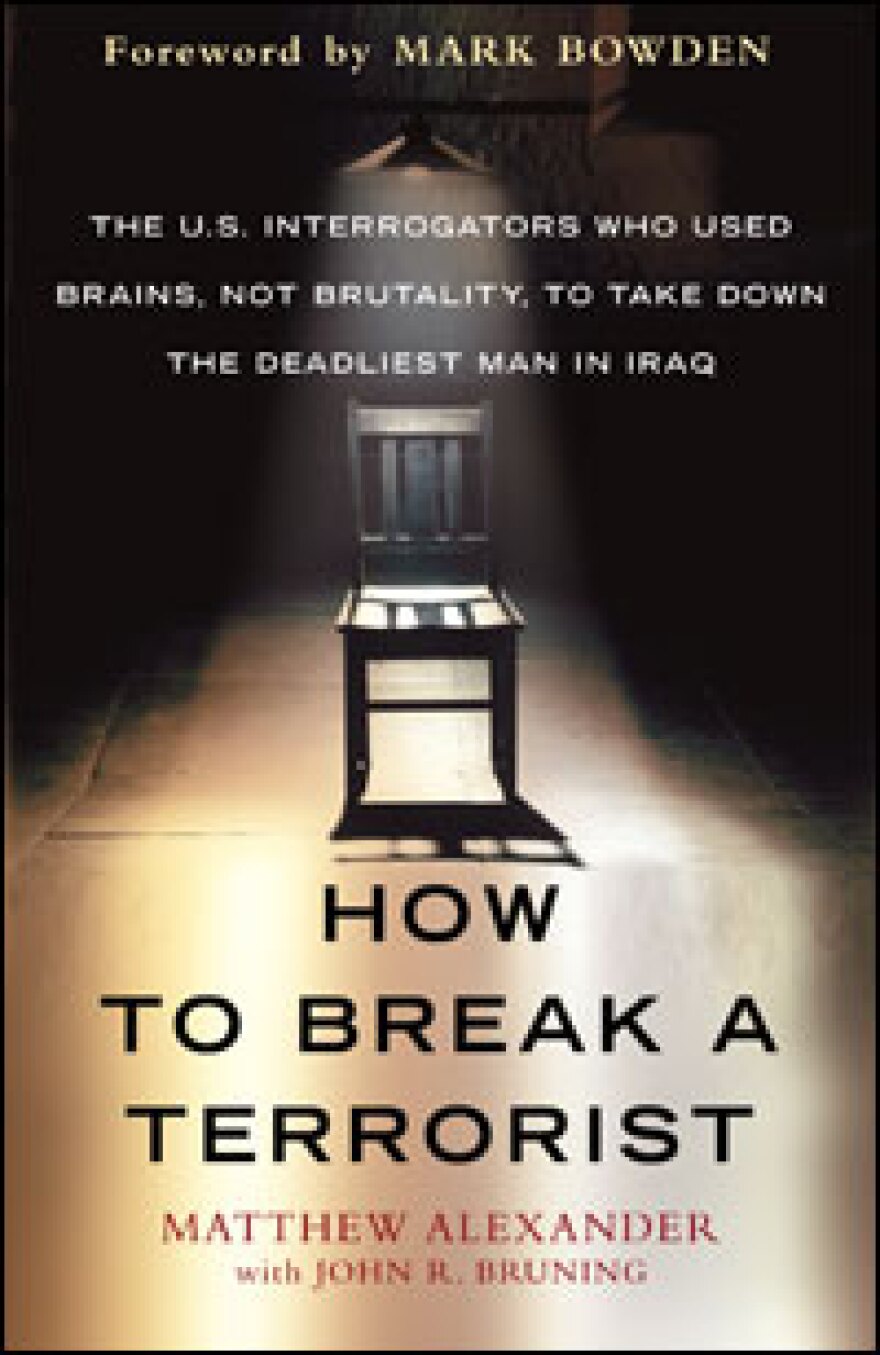

From How To Break A Terrorist by Matthew Alexander with John R. Bruning. Published by Free Press. Copyright 2008. Excerpted by permission of the publisher.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDM3NjYwMjA5MDE1MjA1MzQ1NDk1N2ZmZQ004))