Being a printer was the only job my father ever had, and he loved it. He would work for the newspaper until he retired over forty years later. In all that time he worked side by side with hearing co-workers, but he never really knew them. Like most in the hearing world, they treated him as if he were an alien — primitive, incapable of speech, and lacking human thought: a person to be avoided if possible, and if not, ignored.

After an apprenticeship of many years, my father was issued a union card. It was the proudest moment of his life. It was tangible proof that he was as good as any hearing man. Even in the dark days of the Depression, when one out of four men were out of work, he, a deaf man, could support himself.

And, he reasoned, he could also support a wife. My father was tired of being alone in this hearing world. It was time, he thought, to create his own silent world. A world that would begin with a deaf wife.

One bleak winter day, while we were sitting at the kitchen table, the rain sleeting against the windows of our Brooklyn apartment, his hands told me the rest of his story, in which began my story:

"Sarah was a young girl. She had many friends. She liked to have fun.

"I first noticed her at the beach in Coney Island. She was always laughing. "All the deaf boys were crazy about Sarah. Even the hearing boys.

"There were many handsome boys on the beach. All the young boys had muscles and chocolate tans. They could jump and leap over each other's back. They could do handstands.

"I was older. I didn't have muscles. I couldn't stand on my hands if my life depended on it. I didn't have a brown tan. I would get sunburned. My skin turned red. And then I would peel.

"It didn't matter. The handsome young boys with their chocolate skin and big muscles only wanted to have fun with Sarah. They were not serious boys. They had no jobs. So they had plenty of time to play, and make muscles, and get brown skin from the sun.

"I was a serious man. I had a job. A good job. The best job. I was no longer an apprentice printer. I had a union card, just like the hearing workers.

"I didn't want Sarah just to have fun. I wanted a wife for all time. I wanted a mother for my children. I wanted a partner forever. We would be two deaf people in the hearing world. We would make our own world. A quiet world. A silent world.

"We would be strong together, and strong for our children."

Then, just as the rain stopped and thin rays of sunlight striped the tabletop, my father smiled to himself, his hands thinking ... "Maybe we would have a little fun before the children came." Lost in reverie, his hands, bathed in golden light, now lay silent on the kitchen table. Time passed. I sat and watched his still hands, waiting patiently for them to continue his story. I loved the quiet time we spent together, and I loved the stories his hands contained.

Then my father's hands came alive again, eloquently describing a warm spring afternoon in 1932 Brooklyn.

"I knew I had to make a good impression. I had to dress well. I wore my best suit. Actually, it was my only suit. The big Depression was still going strong, and I watched every dollar."

He tells me his suit was a fine wool serge that cost him two weeks' salary. Its jaunty design was at odds with the feeling of dread that grew in him that day as he set off for the apartment where Sarah lived with her family, having written to her father asking if he might pay a call.

The scene unfolds with cinematic vividness as my father's hands recount each stage of his quest.

He descends with the crowd, down the stairs from the subway platform, sweat dampening his armpits, and exits the station into the frantic gay activity of Sabbath shoppers rushing about, making their last-minute purchases for the evening meal.

The salt scent of the Atlantic Ocean hangs over every shop awning, every outdoor stall, reminding my father, as if he needed such a reminder, how far he had traveled this warm day from his familiar home in the northern leafy village reaches of the Bronx, after one trolley ride and three subway transfers, to the very end of Brooklyn, on the honky-tonk shore of Coney Island. And why has he come here on this warm spring day, sweat pooling at the base of his spine, palms moistly clutching now-wilted store-bought flowers? Today, this very afternoon, my father will meet, for the first time, the family of the girl he has chosen to be his wife.

Unfortunately for him, my future mother, waiting at home, believes he is hopelessly boring and much too old for her; besides, she feels, she's too young to be married, there being so much fun to be had with all the good-looking boys who flutter around her like bees around a hive of honey every weekend on the hot sand of Bay 6, their hands gesturing wildly to gain her exclusive attention. And she could not banish from her mind the image of the hearing golden boy whose attentions she enjoyed so much and who said he loved her.

Glancing nervously at the written directions, my father marches down the broad bustling avenue, so unlike the uneventful Bronx street where he lives. His hands at his sides rehearse the arguments he will employ this afternoon to convince this dark-haired young girl and her father that he is the one to whom she should commit her future. He has been marshaling the arguments in his favor for the past two weeks. He has a steady job and a union card. He is mature and serious. He is a loyal and dependable fellow, calm in an emergency. He can read. He can write. He can sign fluently. And if she will have him, he will love her forever. He finds himself impressed with his qualifications as he cycles through them. He is an up-and-comer. Besides, he has a full head of hair parted perfectly down the middle and a dandy mustache, and is altogether a fine-looking fellow.

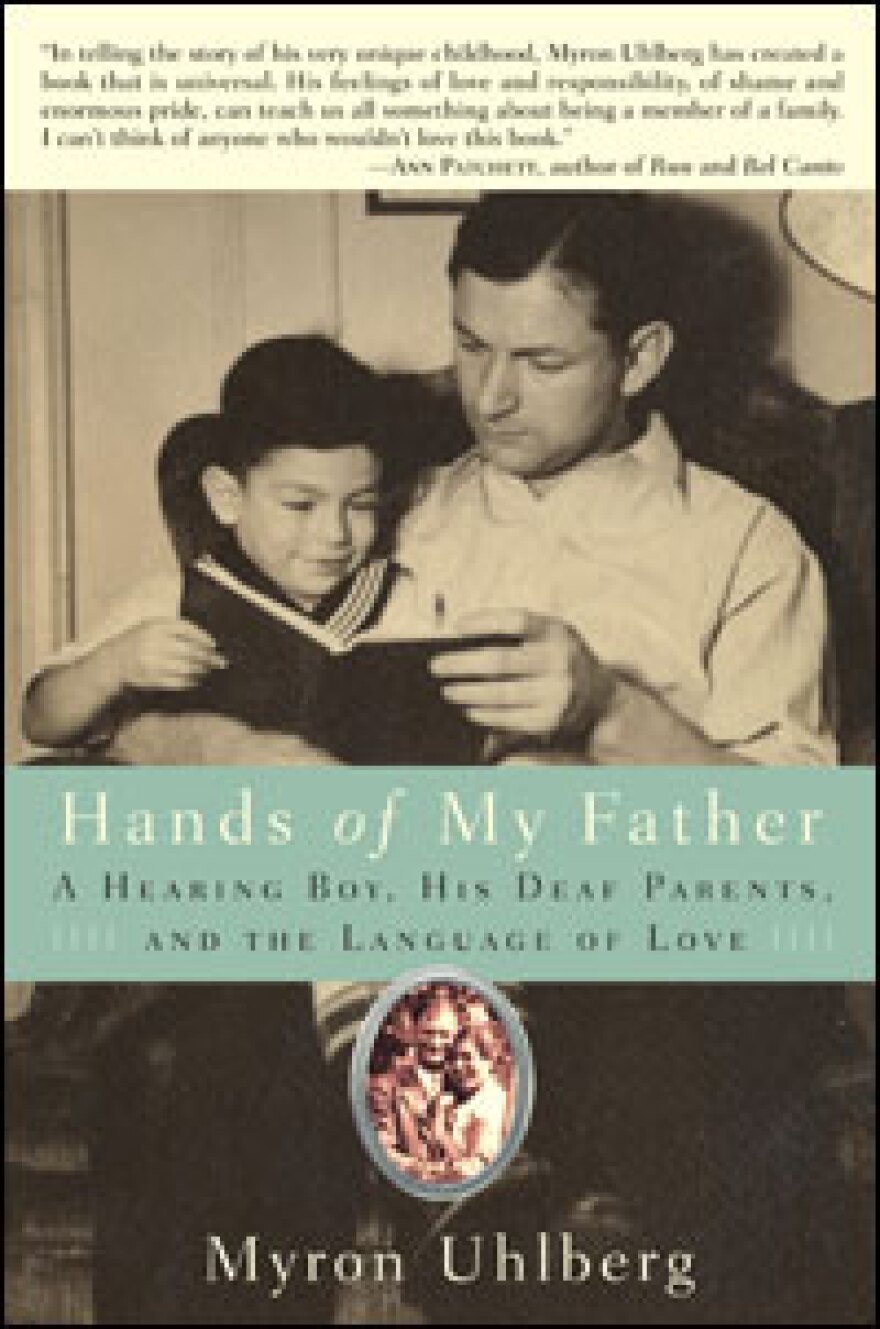

Excerpted from Hands of My Father by Myron Uhlberg Copyright © 2008 by Myron Uhlberg. Excerpted by permission of Bantam, a division of Random House, Inc. All rights reserved.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDM3NjYwMjA5MDE1MjA1MzQ1NDk1N2ZmZQ004))