Coastal Erosion

As soon as the snow melts, I will go to Rass and fetch my mother. At Crisfield I'll board the ferry, climbing down into the cabin where the women always ride, but after forty minutes of sitting on the hard cabin bench, I'll stand up to peer out of the high forward windows, straining for the first site of my island.

This is your favorite book, right? Okay, just checking. (MINE TOO.) Why? Is it the island thing? The song thing? The twin thing? Falling in love with an old captain and your formerly nerdy friend and not getting either one? No. It's that there is no book more quietly, quietly sad, nor one that as brilliantly depicts the psychic disarrangement of childhood without falling prey to convenient justification—say, being funny or heartwarming, or instructive, as in by setting it in stultifying historical period—as this one, which takes sisterly jealousy as neither an object lesson nor a juicy starting point but as the painful, enduring state it is.

Jacob Have I Loved is the story of Sara Louise Bradshaw, christened ineluctably by her fraternal twin, Caroline, as "Wheeze," to her eternal consternation. Caroline is not only generally agreed to be lovely, but also possessed of the kind of shatteringly beautiful voice that makes others pay attention ("Caroline is the kind of person other people sacrifice for as a matter of course") and what Louise takes to be callous disregard for others. (I can now read this only as Caroline's rare—but fair—lack of adolescent self-hatred.) Louise is, of course, nearly paralyzed with envy of her sister—although it's less pure envy than rage and shame at how publicly pale in comparison Louise must seem to everybody else, including even her best friend Cal, a chubby, bespectacled nerd.

The girls have been raised on Rass, a teeny island on the Chesapeake off the Eastern Shore, where their father crabs and their mother, a former mainland schoolteacher, watches over them. Their grandmother, not the cookie-baking type, is suf¬fering from the early stages of dementia and given to following Louise around the house and triumphantly offering damning passages from the Bible:

I struggled to pry the lid off a can of tea leaves, aware that my grandmother had come up behind me. I stiffened at the sound of her hoarse whisper. "Romans nine 13," she said. "As it is written, 'Jacob have I loved, but Esau have I hated.' "

That's totally going to help you work through that insecurity thing about how no one even remembers your BIRTH because your sister almost died and they were all worried about her, especially when your grandmother whips that out right at the moment you're dying over your weird inappropriate crush on a 56-year-old sailor that's returned to the island and you know that no one, ever, not in a million years, would give up their life's savings to let you go study voice in Baltimore. And also: "Wheeze."

Paterson is unflinching about the pain Louise suffers by her second-best status without making Louise's frustration seem like anything but the unattractive, festering blister that it is. Yes, Louise's fundamental rage and pain is something that could probably be handled through a triple dose of CBT, Paxil, and a round of family therapy nowadays. But let's let the pain stand: the few minutes before Caroline exited the womb after her are, as Louise sees it, "the only time in my life I was ever the center of anyone's attention." Louise may be both the main proponent and victim of this belief, but it will take her until adulthood to realize that.

The first insight occurs at the nadir of Louise's adulthood. While Caroline has gone off to a brilliant career at Juilliard, Louise has left school to crab with her father, out on the water with the men in the hard weather, snapping at her mother when she suggests she might want to go to a boarding school on Crisfield—a cheap simulacrum of Caroline's life is far worse than a blatant rejection. Stuck in a deliberate limbo, hiding out from her friends, family, and any romantic prospects, she buries herself in crabbing:

It was work that did this for me. I had never had work before that sucked from me every breath, every thought, every trace of energy.

"I wish," said my father one night as we were eating our meager supper in the cabin, "I wish you could do a little studying at night. You know, keep up your schooling."

We both glanced automatically at the kerosene lamp, which was more smell than light. "I'd be too tired," I said.

"I reckon."

It had been one of our longer conversations.

But, after Cal returns on leave, Louise finds herself pulling on a dress and smearing cheap lotion on her hands, desperately trying to wash off the smell of crab. For her pains, she receives the news that her newly handsome old friend stopped off in New York before coming to Rass to ask Caroline to marry him. But it's not until a rare clear day in spring to wash the windows with her mother that the rage that's been building in Louise since childhood finally comes out. Unable to contain her bitterness at Caroline having escaped with the best of Rass while she is left only the dregs, she assails her mother and is unexpectedly rewarded:

I moved my bucket and chair to the side of the house where she was standing on her chair, scrubbing and humming happily. "I don't understand it!"

The words burst out unplanned.

"What, Louise?"

"You were smart. You went to college. You were good-looking. Why did you ever come here?"

. . . "It seemed romantic—" She began scrubbing again as she talked. "An isolated island in need of a schoolteacher. I felt—" She was laughing at herself. "I felt like one of the pioneer women, coming here. Besides—" She turned and looked at me, smiling at my incomprehension. "I had some notion I would find myself here, as a poet, of course, but it wasn't just that."

The anger was returning. There was no good reason for me to be angry but my body was filled with it, the way it used to be when Caroline was home. "And did you find yourself here on this little island?" The question was coated with sarcasm.

She chose to ignore my tone. "I found very quickly," she scratched at something with her fingernail as she spoke, "I found there was nothing much to find."

Louise cannot contain herself:

"Let me go. Let me leave!"

"Of course you may leave. You never said before you wanted to leave."

And, oh, my blessed, she was right. All my dreams of leaving, but beneath them I was afraid to go. I had clung to them, to Rass, yes, even to my grandmother, afraid that if I loosened my fingers one iota, I would find myself once more cold and clean in a forgotten basket.

"I chose the island," she said. "I chose to leave my own people and build a life for myself somewhere else. I certainly wouldn't deny you that same choice. But," and her eyes helped me if her arms did not, "oh, Louise, we will miss you, your father and I."

I wanted so much to believe her. "Will you really?" I asked. "As much as you miss Caroline?" "More," she said, reaching up and ever so lightly smoothing her hair with her fingertips.

And of course, now that Louise has to admit that she's held herself back more than anyone else has (again, some family therapy and a dose of Paxil), she finds that everyone around her, even the captain, whom she'd loved—to her shame—as a child, has only been waiting for her to notice:

I sat down on the couch near his chair. There was no need to pretend, I knew. "I had hoped when Cal came home—"

He shook his head. "Sara Louise. You were never meant to be a woman on this island. A man, perhaps. Never a woman."

"I don't even know if I wanted to marry him," I said. "But I wanted something." I looked down at my hands. "I know I have no place here. But there's no escape."

"Pish."

"What?" I couldn't believe I'd heard him correctly.

"Pish. Rubbish. You can do anything you want to. I've known that from the first day I met you—at the other end of my periscope."

It's admirable that Paterson refuses to deny Louise her pain, though everyone around her knows it's unjust, unnecessary— even self-generated. But that's the horribly ironic nature of pain, of course—not that we can't help but be taken over by it, but that, despite ourselves, we may be creating it.

Louise chooses to go to the mountains, to become a nurse practitioner, and even though she marries and has her own child, she still isn't able to let her sister go, until one night, when she's called to help a young mother whose husband has clearly been smacking her around give birth to twins. One twin comes easily, and then the second, blue, is in danger, until Louise finally manages to get him stable. But then she realizes she's repeated her own past:

"Where is the other twin?" I asked, suddenly stricken. I had completely forgotten him. In my anxiety for his sister, I had completely forgotten him. "Where have you put him?"

"In the basket." She looked at me, puzzled. "He's sleeping."

"You should hold him," I said. "Hold him as much as you can. Or let his mother hold him."

Louise realizes that Caroline's anointment at the moment of their birth as the most valuable twin was not personal, not some grim finger of fate consigning Louise to second-place status. It was only practical—and she was as able to be guilty of it as anyone. It was a harm leveled on her by distraction, not intention—and once she sees that and reverses it, she becomes her own redeemer.

But I was trying not to cry. Let's see: I just want to point out that this is one of my favorite covers of all time and I always thought Louise looked prettier than Caroline. So there.

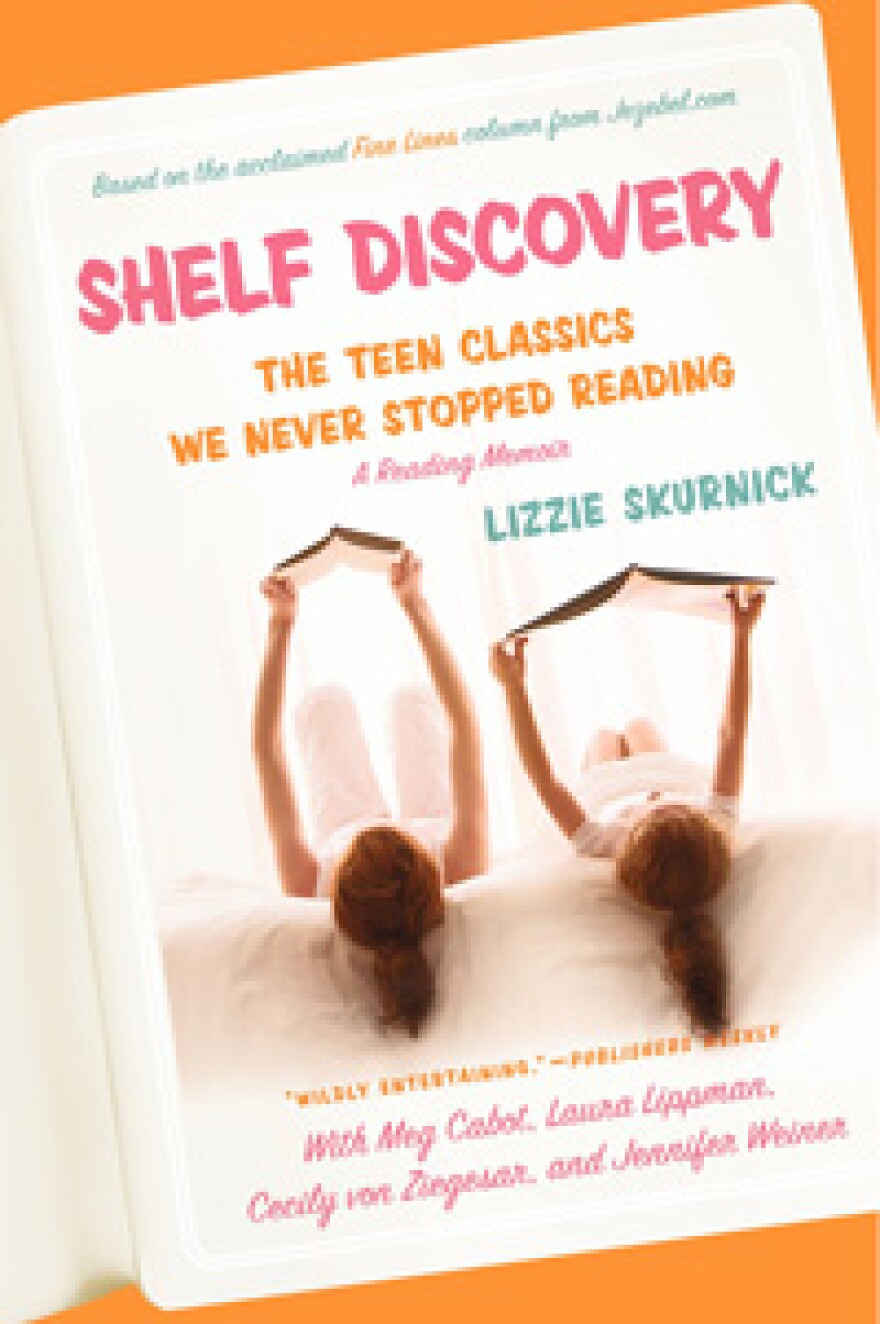

From Shelf Discovery: The Teen Classics We Never Stopped Reading. Copyright © 2009 by Elizabeth Skurnick. Published by Avon, a division of Harper Collins. Used by permission of the publisher. All rights reserved.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDM3NjYwMjA5MDE1MjA1MzQ1NDk1N2ZmZQ004))