1

THE MECCA: Twinsburg

I'm twinless in Twinsburg, Ohio.

I've come to this little Cleveland suburb on a perfect sunny weekend in August for the annual twins convention. Thousands of sets of twins fly or drive from all over the world for a three-day twins party; imagine hundreds of identically dressed pairs milling around, stealing glances at one another, snapping furtive photographs of one another, eating funnel cakes, and buying buttons that say things like it takes two to do Twinsburg, or I'm the original. she's the copy, or mom likes me best.

Twinsburg was named by the Wilcox twins, Moses and Aaron, who founded the village in 1819 and succeeded in changing its name from Millsville to Twinsburg. In exchange, they paid the township twenty dollars and donated property to build the first school. The Wilcoxes were not only indistinguishably identical; according to the municipal Web site, they "married sisters; had the same number of children; contracted the same fatal ailment; died within hours of each other and are buried in the same grave."

Twins Days was started in 1976 as a way to celebrate the Bicentennial and boost tourism; in that first year, thirty-seven sets of twins attended. Today, it's a multinational swarm of thousands; in the year I attended — 2006 — there were twins from Germany, Switzerland, Spain, and Great Britain, along with twins from all over the United States. Two thousand sixty-four sets — sets — descended on Twinsburg in matching plaids, stripes, and polka dots to meet and marvel at one another. Every generation was represented — from stroller to wheel-chair — with every age in between.

It feels odd to be solo on the registration line. But it's also a relief, because the idea of having my twin here is unthinkable. Robin would squirm at the spectacle: pair after pair — copy after copy — in matching straw hats, matching suspenders, matching lime green dresses. This is a self-selected group: the Gung-Ho Twins, the kind who are game to welcome the novelty, the public curiosity, the party, and each other.

Robin isn't that kind of twin. Which means we're not among those who spent hours on the phone coordinating outfits and travel plans for this occasion, who designated this weekend as their annual escape from spouses and children. Robin didn't cosign my Enterprise rental car at the Cleveland airport earlier that morning, she won't be sleeping in the double bed next to mine at the Courtyard Marriott, and she isn't here to pick up her name tag, which I'm nevertheless accepting now on her behalf at the registration desk. (I'd given both our names in advance, because we were asked to, and because I felt illegitimate without it.)

"I think Twinsburg attracts a subset of identical twins," says Nancy Segal, who has studied and written about twins for thirty years, created the Twin Studies Center at the University of Fullerton, and also happens to be an avid swing dancer. "I think Twinsburg serves a useful purpose for those twins who always get stared at and feel uncomfortable about it. In Twinsburg, they're in perfect company and nothing's unusual."

"Obviously there's a need for it," says Sandy Miller, cofounder of the Twins Days festival. "It's somewhere where twins can be in the majority, where they can be themselves and enjoy other twins. We have a real family here. It's amazing what this means to them. This is their day. Their weekend."

There are other twins festivals — in Canada and Japan, for example — but Twinsburg trumps them all for its annual numbers. "That's according to the Guinness Book," Miller says. Her fraternal twin sons grew up going to Twins Days; one met his wife here, an identical twin. "When I had my twins years ago, it was novel," Sandy recalls. "Now it's almost an everyday occurrence. And then, with all the fertility drugs, you get the Super Twins." She says that accidental twins still feel like the genuine article. "It's a joke between some of the twins that have been coming to Twins Days for a long time: 'We're real twins. You're not.' "

Jean Labaugh, fifty-one, and her identical twin, Joanie Warner, whom I meet early on, are wearing halter-top dresses and red rubber clogs. They tell me they happened to buy exactly the same Clairol hair color, even though they live in different states. And they feel each other's pain.

"One time I had a deep throbbing in my leg all night," Jean recounts. "It went all the way to the bone. And Joanie called me the next day and told me she broke her ankle."

After marveling, I ask why they come to Twinsburg.

"Oh, it's so nice just to see other twins here," Jean enthuses, "to see what they're like, and hear what their lives are like."

I venture that some people might be overwhelmed by such a concentration of doubles.

Joanie shakes her head. "It's beautiful. Especially to see the guys be able to celebrate their uniqueness. To see them be so close together."

I go through the charade of actually accepting Robin's ID on a string from the woman behind the registration table, pretending I'll be giving it to my sister later when she "arrives." The truth is: I don't want to admit that my twin isn't coming. That would be an admission that I've arrived under false pretenses. I came to report on twins, but I also belong here because I am one. If Robin isn't beside me, I might be an imposter.

But Robin isn't here, because I didn't invite her. I couldn't bring myself to say, "Come see other twins with me." She's never been innately curious about other pairs simply because we happen to be twins, and until recently, neither have I. Growing up, we never sought out twin friends. When you're a twin, who needs more twins?

We've never been passionate about our twinship for its own sake. We're passionate about each other. I know we both feel lucky to be twins together, but that hasn't made us seek out other twosomes, or twin events.

So I came to Twinsburg on my own. But I didn't expect to feel so unmoored without Robin.

At the welcome desk, I notice two elderly men with exactly the same overgrown eyebrows, dressed in matching blue-striped shorts, blue-striped shirts, and newly purchased sneakers, which they later tell me were a fifteen-dollar bargain at Kmart.

"This is our twenty-third year!" one of them boasts to the woman at the check-in.

When they've received their registration packets and stepped away from the table, I approach the stooped duo and ask their age. "Seventy and three-quarters!" says one, who introduces himself as David. "Walter's older by eight minutes."

David and Walter Oliver still live together — in the same house they grew up in, in Lincoln Park, Michigan. David is clearly the talker. "Walter was too small and they had to keep him in the hospital for three weeks." He seems gleeful about this.

"I was under five pounds," Walter adds morosely.

"We both have keratoconus in the left eye," David reports. "We've both got neuropathy in our feet."

"And we both have diabetes," Walter pipes up.

And they always dress alike?

"We wear the same clothes every time we go to a twins gathering," David explains. "It's sort of an unwritten thing that all twins do."

The Olivers are suddenly joined by Janet and Joyce, seventy-six, in matching blue tops, who also hail from Michigan.

"We met Joyce and Janet at the International Twins Convention in Toronto, Canada," David explains. "Nineteen eighty-two."

Janet and Joyce, who have different last names by marriage, are distinguishable only because Joyce seems more frail.

"I'm the young one," announces Janet, who wears her white hair cropped exactly like her sister's. "We're five minutes apart. She's older. I'm married fifty-five years. She's divorced."

Joyce pipes in: "When you're that close to your twin, you have to make sure that the husbands are into the twin thing. Otherwise, the marriages will not work."

They went to their first twins convention in 1946 in Muncie, Indiana, and they've been coming to Twinsburg for decades. When I admit it's my first time, they tell me what to look forward to, including the research tents in which twins sign up for studies comparing twins' teeth, skin, sense of taste, and hearing.

Janet: "Last year, one of the tents offered us twenty dollars to smell things."

Joyce: "It took too long."

I ask these four elderly twins why they keep coming back.

"IT'S FASCINATING TO MEET TWINS!" David almost shouts. "And we've been trying to find females for the last fifty years."

So they've never been married?

"Never." David shakes his head. The smile vanishes.

I ask if they think they never married because they are twins; maybe their unique intimacy prevented other kinds.

"No," David says, dismissing my armchair analysis. "Females have ignored both of us all our life." (I notice his use of the singular: "life.")

I ask David why he thinks women take no notice. "I have no idea," he says. "It's very painful. To live an entire lifetime without having a loving relationship." He seems abruptly bereft. "Every year we come here to find twins for us to marry."

David asks me where my twin is and I fumble a quick explanation.

"It's hard to be a twin here without your twin," he declares, reading my mind.

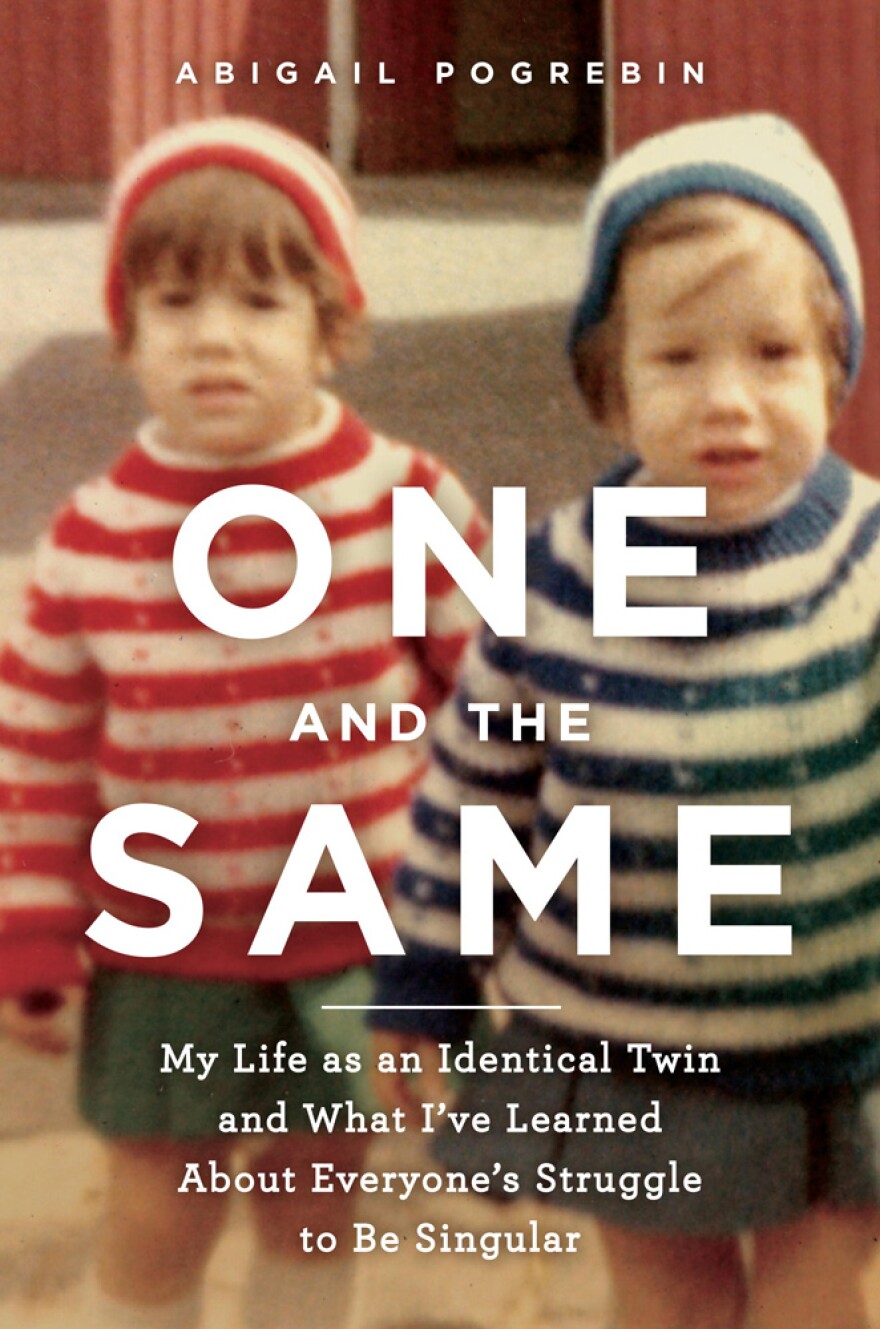

Excerpted from One and the Same by Abigail Pogrebin Copyright 2009 by Abigail Pogrebin. Excerpted by permission of Doubleday, a division of Random House, Inc. All rights reserved.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDM3NjYwMjA5MDE1MjA1MzQ1NDk1N2ZmZQ004))