There's a saying in Arabic: Fi khibz wa meleh bainetna—there is bread and salt between us. It means that once we've eaten together, sharing bread and salt, the ancient symbols of hospitality, we cannot fight. It's a lovely idea, that you can counter conflict with cuisine. And I don't swallow it for a second.

Just look at any civil war. Or at our own dinner tables, groaning with evidence to the contrary.

After September 11, liberal New Yorkers flocked to Arabic restaurants, Afghan, even Indian—anything that seemed vaguely Muslim, as if to say, "Hey, we know you're not the bad guys. Look, we trust you, we're eating your food." New York newspapers ran stories about foreigners and their food, most of which followed much the same formula: the warmhearted émigré alludes mournfully to troubles in his homeland; assures the readers that not all Arabs/Afghans/Muslims are bad; and then shares his recipe for something involving eggplants. They were everywhere after September 11, photos of immigrants holding out plates of food, their eyes beseeching, "Don't deport me! Have some hummus!" But a lot of them did get deported, and American soldiers got sent to Afghanistan and Iraq. A decade later, the lesson seems clear: You can eat eggplant until your toes turn purple, and it won't stop governments from going to war.

But then again, there is something about food. Even the most ordinary dinner tells manifold stories of history, economics, and culture. You can experience a country and a people through its food in a way that you can't through, say, its news broadcasts.

Food connects. In biblical times, people sealed contracts with salt, because it preserves, protects, and heals—an idea that goes back to the ancient Assyrians, who called a friend "a man of my salt." Like Persephone's pomegranate seeds, the alchemy of eating binds you to a place and a people. This bond is fragile; people who eat together one day can kill each other the next. All the more reason we should preserve it.

Many books narrate history as a series of wars: who won, who lost, who was to blame (usually the ones who lost). I look at history as a series of meals. War is part of our ongoing struggle to get food—most wars are over resources, after all, even when the parties pretend otherwise.

But food is also part of a deeper conflict, one that we all carry inside us: whether to stay in one place and settle down, or whether to stay on the move. The struggle between these two tendencies, whether it takes the form of war or not, shapes the story of human civilization. And so this is a book about war, but it is also about travel and migration, and how food helps people find or re-create their homes.

One of my old journalism professors, a man with the unforgettable name of Dick Blood, used to roar that if you want to write the story, you have to eat the meal. He was talking about Thanksgiving, when reporters visit homeless shelters, collect a few quotes, and head back to the newsroom to pump out heartwarming little features without ever tasting the turkey. But

I've found that this command—"You have to eat the meal"— is a good rule for life in general. And so whenever I visit a new place, I pursue a private ritual: I never let myself leave without eating at least one local thing.

We all carry maps of the world in our heads. Mine, if you could see it, would resemble a gigantic dinner table, full of dishes from every place I've been. Spanish Harlem is a cubano. Tucson is avocado chicken. Chicago is yaprakis; Beirut is makdous; and Baghdad—well, Baghdad is another story.

In the fall of 2003, I spent my honeymoon in Baghdad. I'd married the boyfriend, who was also a reporter, and his newspaper had posted him to Iraq. So I moved to Beirut, with my brand-new husband and a few suitcases, and then to Baghdad.

For the next year, we tried to act like normal newlyweds. We did our laundry, went grocery shopping, and argued about what to have for dinner like any young couple, while reporting on the war. And throughout all of it, I cooked.

Some people construct work spaces when they travel, lining up their papers with care, stacking their books on the table, taping family pictures to the mirror. When I'm in a strange new city and feeling rootless, I cook. No matter how inhospitable the room or the streets outside, I construct a little field kitchen. In Baghdad, it was a hot plate plugged into a dubious electrical socket in the hallway outside the bathroom. I haunt the local markets and cook whatever I find: fresh green almonds, fleshy black figs, just-killed chickens with their heads still on. I cook to comprehend the place I've landed in, to touch and feel and take in the raw materials of my new surroundings.

I cook foods that seem familiar and foods that seem strange. I cook because eating has always been my most reliable way of understanding the world. I cook because I am always, always hungry. And I cook for that oldest of reasons: to banish loneliness, homesickness, the persistent feeling that I don't belong in a place. If you can conjure something of substance from the flux of your life—if you can anchor yourself in the earth, like Antaeus, the mythical giant who grew stronger every time his feet touched the ground— you are at home in the world, at least for that meal.

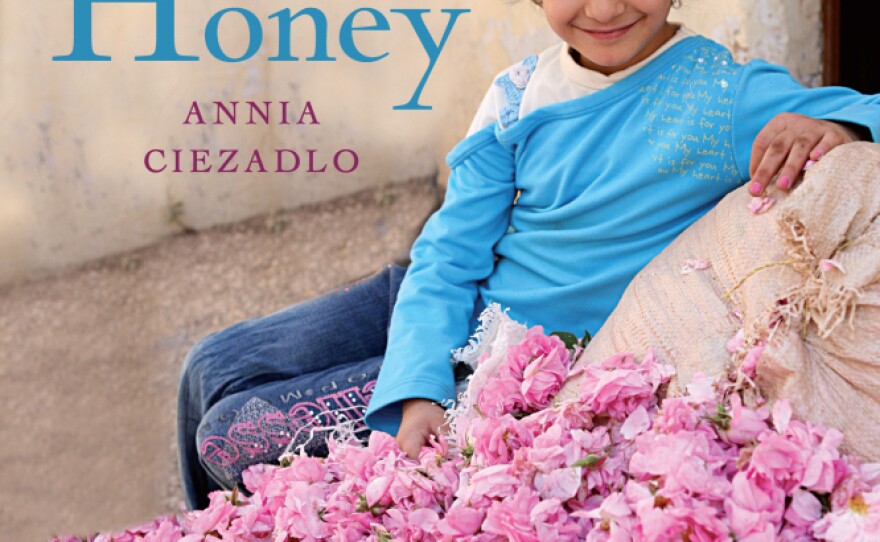

Excerpted from Day of Honey by Annia Ciazadlo. Copyright 2011 by Annia Ciazadlo. Excerpted by permission of Free Press, a division of Simon & Schuster. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDM3NjYwMjA5MDE1MjA1MzQ1NDk1N2ZmZQ004))